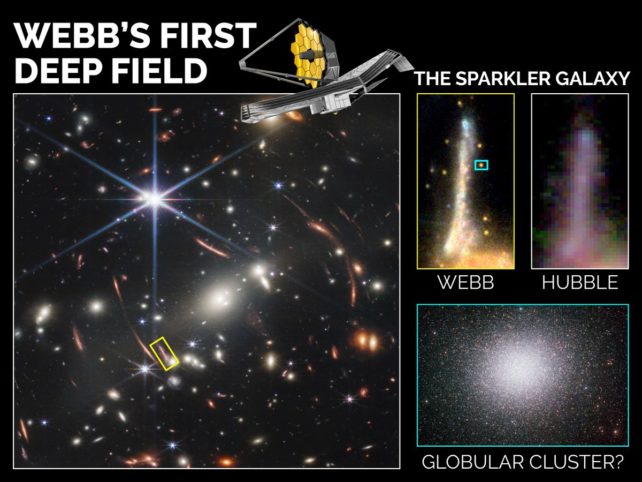

The very first deep field image from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has just delivered a new treasure from the early Universe.

In a splash of light that has traveled for 9 billion years to reach us, astronomers have spotted clusters of stars sparkling around a distant galaxy they have named the Sparkler.

These clusters, whatever their nature, are very interesting indeed: could they be younger clumps, bursting with more recent star formation, or older globular clusters that could contain an elusive population of stars, those that were the first to appear in the nascent Universe?

A team of researchers has just determined that at least some of the clusters shimmering around the galaxy are of the latter kind – making them the most distant globular clusters we've found yet.

"Looking at the first images from JWST and discovering old globular clusters around distant galaxies was an incredible moment, one that wasn't possible with previous Hubble Space Telescope imaging," says astrophysict Kartheik Iyer of the University of Toronto in Canada, who co-led the study.

"Since we could observe the sparkles across a range of wavelengths, we could model them and better understand their physical properties, like how old they are and how many stars they contain.

"We hope the knowledge that globular clusters can be observed from such great distances with JWST will spur further science and searches for similar objects."

Globular clusters are pretty common in local space. We know of about 150 or so in the Milky Way, and they're something of a puzzle. They are extremely dense, spherical clusters of around 100,000 to 1 million stars that are all the same age and often extremely old – some of them almost as old as the Universe.

They are thought of as 'fossils' that can tell us about the state of the Universe at the time the stars formed.

However, we don't know a lot about how they formed, or where they came from. And it's pretty challenging to figure out how old they actually are.

Finding them in the early Universe, with enough data to determine their nature, isn't easy either. Across such vast distances, small, dim objects become much harder to resolve.

But, well, JWST is just bloody good at being the biggest, most sensitive space telescope ever launched.

One of the first images it released, titled Webb's First Deep Field, comprising a total 12.5 hours' exposure time, is the highest resolution image of the early Universe ever obtained.

Even so, we might have missed the Sparkler, but for a quirk of alignment: between us and it sits a galaxy cluster called SMACS 0723. The gravitational curvature of space-time distorts the light from the distant galaxy, not just magnifying it by a factor of 100, but by replicating it – not once, but twice. This 'triplicate' distortion of the galaxy gives more data to analyze.

The team made a thorough study of the light emitted by the 12 clusters they identified, and for five of them, made no detection of the oxygen expected for a cluster that is actively forming stars. This is what led them to the conclusion that the objects are globular clusters that are no longer generating new stars, a state referred to as quiescence.

"Because the Sparkler galaxy is much farther away than our own Milky Way, it is easier to determine the ages of its globular clusters," says astronomer Lamiya Mowla of the University of Toronto, who co-led the study.

"We are observing the Sparkler as it was 9 billion years ago, when the Universe was only four-and-a-half billion years old, looking at something that happened a long time ago.

"Think of it as guessing a person's age based on their appearance – it's easy to tell the difference between a 5- and 10-year-old, but hard to tell the difference between a 50- and 55-year-old."

If they are globular clusters – which could be confirmed through additional spectroscopy to study their chemical compositions – they could represent some of the earliest known objects with quenched star formation, the researchers say. And it could offer some insight into the formation of globular clusters.

The age of the clusters suggests that they formed around the time the Universe, previously dark and opaque, became transparent, allowing light to stream freely. This means that their formation could be connected to the earliest stages of galaxy formation.

"These newly identified clusters were formed close to the first time it was even possible to form stars," says Mowla.

The ghostly clusters drifting around our own Milky Way may have just become even more interesting.

The team's research has been published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.