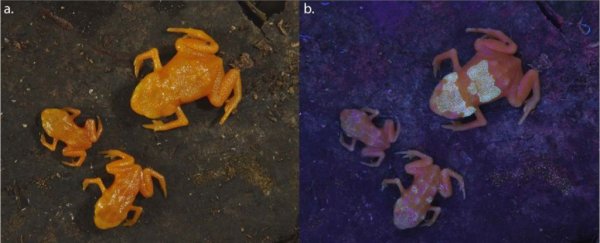

Deep in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest live tiny frogs that are bright orange, toxic, and glow ultraviolet, thanks to revelations from new research.

It's the first known case of an amphibian showing "exceptional" fluorescence right through their skin.

"The origin of the fluorescence lies in the dermal bone of the head and back, visible through a particularly thin skin," explain the researchers in a new paper about the work.

These toxic little guys, called pumpkin toadlets (Brachycephalus ephippium and B. pitanga) are around the size of a fingernail (12 to 20 millimetres), and make a buzzing noise when looking for a mate.

But when researchers discovered the froglings can't actually hear their own mating calls because they lack a middle ear bone, the team looked to other potential mechanisms explaining how the pumpkin toadlet finds love.

Shining a UV light over the frogs revealed a fascinating sight.

"The fluorescent patterns are only visible to the human eye under a UV lamp. In nature, if they were visible to other animals, they could be used as intra-specific communication signals or as reinforcement of their aposematic coloration, warning potential predators of their toxicity," said one of the researchers, Sandra Goutte, from New York University Abu Dhabi.

"However, more research on the behaviour of these frogs and their predators is needed to pinpoint the potential function of this unique luminescence."

You can see in the video below just how striking it is.

Fluorescence has been discovered in many species of animals, and bones always fluoresce under UV (as you can check by showing off your teeth under a UV light)

However, usually bones don't glow through skin, which makes this find so exciting. The fluorescence seems to be visible because the skin on the backs of the toadlets is not just super thin, but also lacks pigmented cells that would normally block any light shining from within.

Despite the excitement, it's important to note that we don't know if the frogs themselves can see this sparkle, so it may not necessarily be related to their mating needs.

But it does look impressive, and it looks like pumpkin toadlets have more secrets than you'd expect from a teeny tiny orange amphibian.

The research has been published in Scientific Reports.