The most isolated vertebrates in the world are now so inbred that researchers worry they won't be around for much longer.

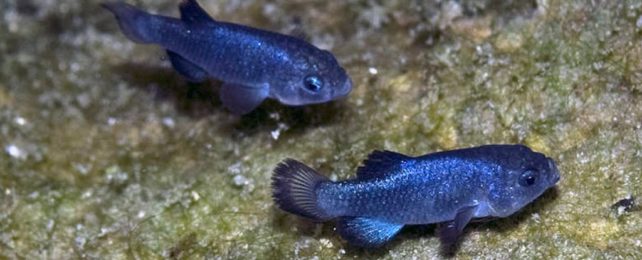

For over 10,000 years, a small population of pupfish has lived only in Nevada's Devils Hole, a famous underground oasis tucked away in the desert borderlands of Death Valley National Park.

The limited habitat is a 152-meter-deep (500 feet) cave, making it the smallest known abode for any creature with a backbone – and the extreme conditions are taking their genetic toll.

After sequencing the genome of eight pupfish from Devils Hole, biologists at the University of California, Berkeley, found that the fish have interbred to such an extent that the average individual shares about 58 percent of its genome with its family members.

"High levels of inbreeding are associated with a higher risk of extinction, and the inbreeding in the Devils Hole pupfish is equal to or more severe than levels reported so far in other isolated natural populations, such as the Isle Royale wolves in Michigan, mountain gorillas in Africa and Indian tigers," says integrative biologist and lead researcher Christopher Martin from UC Berkeley.

That shockingly high level of genome crossover is akin to other endangered species like Florida panthers (Puma concolor), Isle Royale wolves (Canis lupus), and mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei), all of which are suffering from extreme population declines.

When researchers at Berkeley compared their results to other species of pupfish elsewhere in the world, they found only about 10 to 30 percent of individual pupfish genomes are usually identical. The Devils Hole has clearly exacerbated the situation.

It's possible, for instance, that Devils Hole pupfish are accumulating genetic variants that might make it harder for them to survive.

Devils Hole is already scarce in food and oxygen, but according to the recently sequenced genomes, some pupfish alleles closely involved in reproduction and survival in low oxygen conditions appear to have lost their function or been deleted over time.

The good news is that the mutations have been in circulation for a while now.

When researchers sequenced the genome of a preserved Devils Hole pupfish from a museum collection, they found evidence for high levels of inbreeding since 1980 at least.

That was long before the population plummeted to just a few dozen individuals in 2007 and again in 2013. Today, Devils Hole pupfish number about 175. Scientists consider them critically endangered, and no one really knows why they are disappearing. Now researchers want to figure out whether any genes are responsible for those recent losses.

"Part of the question about these declines is whether they may be due to the genetic health of the population," explains Martin.

"Maybe the declines are because there are harmful mutations that have become fixed because the population is so small."

Human activity, like groundwater pumping, probably isn't helping, and natural events, like earthquakes, can also sometimes shake up the underground refuge: If waves get big enough in Devils Hole, they can squash pupfish eggs and rip off algae from the cavern's sunlit shelf.

Since these are some of the only nutrients the pupfish have access to, such events can be disastrous.

So, too, could rising temperatures. If climate change heats up the water content of Devils Hole beyond its constant 33 degrees Celsius (91.4 degrees Fahrenheit), resident pupfish may not be able to reproduce as quickly or efficiently.

Genetic variation is thought to be crucial for animal survival because it means there is more opportunity for future generations to adapt to changing conditions.

But not all mutations are helpful, and some can get dragged along when there are high levels of inbreeding in a population.

Biologists hope to use the genomes of small populations like Devils Hole pupfish to better understand these evolutionary dynamics and what can be done to save the fate of endangered animals.

If a particular mutation, for instance, is found to reduce the ability of Devils Hole pupfish to survive in low oxygen, then maybe technology like CRISPR could help scientists delete that allele from the mix, or restore other genes that were previously lost.

The researchers identified a total of 15 genes that have vanished from the genome of the Devils Hole pupfish.

Replacing lost aspects of a genome is a controversial idea, but it's a possibility that is currently being explored by some biologists and conservationists.

"Our future work is to actually look at what these deletions do," says Martin.

"Do they increase tolerance of hypoxia? Do they decrease tolerance of hypoxia? I think those two scenarios are equally plausible at this time."

Once we know what's going on in Devils Hole, scientists can make a more informed choice about how to save resident pupfish.

The study was published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B.