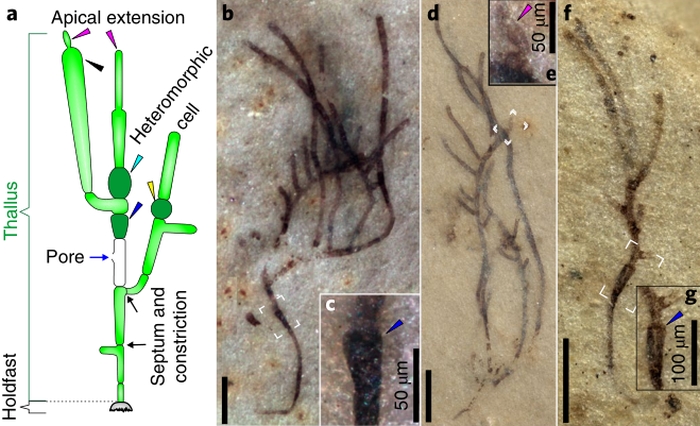

Strange, vein-like shadows imprinted in ancient rocks are some of the most important clues yet in piecing together the timeline of photosynthesis. At 1 billion years old, the tiny fossils are the oldest example of green algae we've ever discovered.

Even from all those aeons ago, the fossils show evidence of characteristics in common with modern algae. They represent multicellular organisms with branching structures and even root systems.

Palaeontologists have named the newly discovered, ancient algae Proterocladus antiquus, and it beats the previous record-holder - the fragmentary Proterocladus, 800 million years old (it's possible they're both the same species).

This discovery suggests seaweed were already thriving in the ocean, long before plants migrated to dry land.

"The entire biosphere is largely dependent on plants and algae for food and oxygen, yet land plants did not evolve until about 450 million years ago," said palaeontologist Shuhai Xiao of Virginia Tech.

"Our study shows that green seaweeds evolved no later than 1 billion years ago, pushing back the record of green seaweeds by about 200 million years."

(Tang et al., Nature Ecology & Evolution, 2020)

(Tang et al., Nature Ecology & Evolution, 2020)

The fossils themselves are tiny, just a few millimetres long - flea-sized smears on sedimentary rock found in the Nanfen Formation in Liaoning Province, North China. But when studied under a microscope, their delicate, branching forms are crystal clear.

Older algae fossils have been found - a red alga called Bangiomorpha pubescens, which was dated to around 1.047 billion years ago. It's also an important find for our understanding of photosynthesis, but P. antiquus is different because it's green.

It's thought that green plants - Viridiplantae - emerged sometime between 2.5 billion and 635 million years ago. Because ancient plant fossils are rare, narrowing that timeline down has been extremely difficult. Scientists also don't know when they evolved from single-celled to multicellular organisms, or even where they started out.

Some believe that, just like multicellular animals, Viridiplantae started off in the ocean as seaweeds before moving onto dry land and evolving into all the different plants we have today, from the mightiest redwood to the smallest moss.

Others, however, believe that freshwater rivers and lakes gave birth to plants; from there, they moved into the ocean, before finally ending up on land.

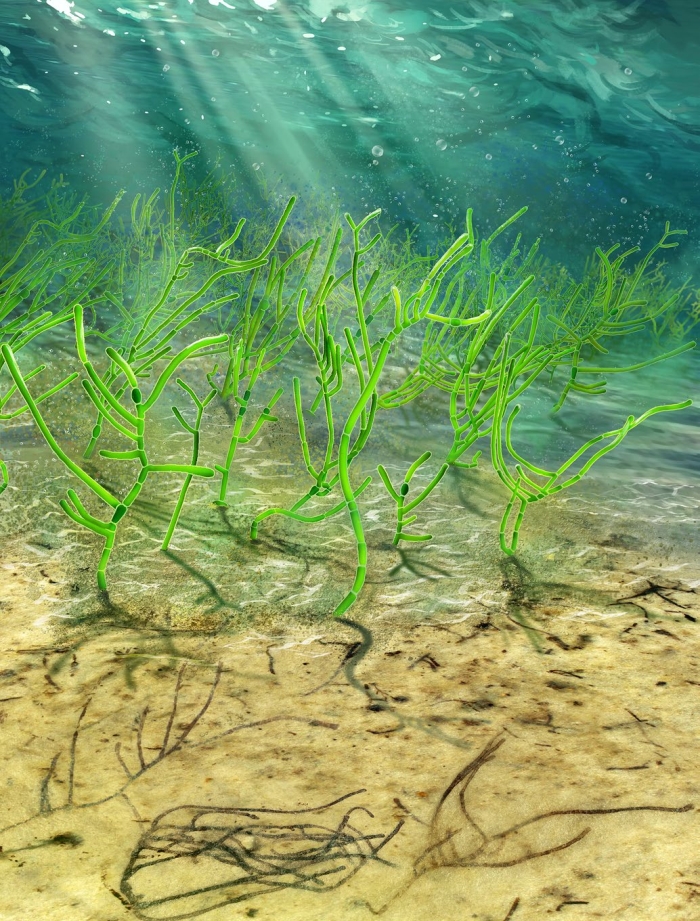

P. antiquus supports an oceanic origin - because it's extremely similar to seaweeds that are around today.

Artist's reconstruction of P. antiquus. (D. Yang)

Artist's reconstruction of P. antiquus. (D. Yang)

"There are some modern green seaweeds that look very similar to the fossils that we found," Xiao said. "A group of modern green seaweeds, known as siphonocladaleans, are particularly similar in shape and size to the fossils we found."

The branching structures and tiny sizes have led the team to hypothesise that P. antiquus is a type of ancient siphonocladalean, although they note that it cannot be ruled out that P. antiquus developed a siphonocladalean morphology independently, and is now extinct.

Nevertheless, even if they were distinct species, their similarity suggests a similar environment; that is, the ocean. That finding, in turn, can help us also understand the ancient ocean environment.

And, of course, it tells us more about the complicated and mysterious plant family tree.

"These seaweeds display multiple branches, upright growths, and specialised cells known as akinetes that are very common in this type of fossil," Xiao said.

"Taken together, these features strongly suggest that the fossil is a green seaweed with complex multicellularity that is circa 1 billion years old. These likely represent the earliest fossil of green seaweeds."

The research has been published in Nature Ecology & Evolution.