Today, art and science are often seen as two wildly different pursuits. Historically, the pair are not so easily distinguished.

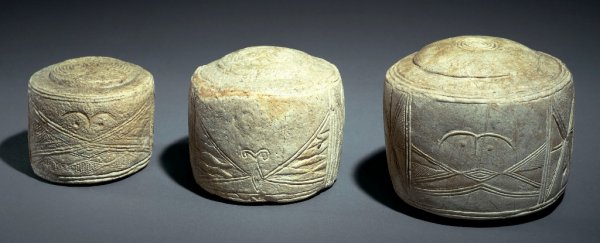

Ever since the Folkton Drums were first discovered 130 years ago, the three chalk cylinders have been praised for their remarkable and intricate decorations, carved more than 4,000 years ago in Britain.

Now, a new study suggests there's more to these ancient artefacts than just a pretty face. Hidden within their beautiful complexity, researchers think they have uncovered an ancient form of measurement, a prehistoric 'tape measure' if you will.

By wrapping a cord around each drum a fixed number of times, Neolithic Britons would have been able to measure out a standard unit of length that could have come in handy when constructing concentric monuments - such as Stonehenge.

While all three of the drums are a slightly different size, the authors found that the circumference of each can be used to measure 3.22 metres.

At the time, this specific measurement was known as the 'long foot' - about 10.5 modern feet - and it's a length commonly observed in ancient British monuments like Stonehenge and the Southern Circle at Durrington Walls.

Measuring out the perfect stone for these monuments would have been quite simple with any one of these drums, all of which could be easily carried back and forth between the various quarries in Britain.

A cord that is 3.22 metres long, for instance, would wrap around the circumference of the smallest drum exactly ten times, eight times around the medium-sized drum, and seven times around the largest drum.

The three chalk drums were first found in Yorkshire in 1889, placed in the grave of a child who was buried sometime during the end of the Stone Age and the beginning of the Bronze Age.

Yet even though we've had over a hundred years to research them, the purpose of these rare objects has long remained a mystery.

"These findings show how important it is to continue to research artefacts in museum collections, and the value in collaborative research for understanding prehistory," says Anne Teather from the University of Manchester.

The authors are now arguing that these beautiful pieces of art are actually evidence of a prehistoric standard of measurement, used widely throughout Britain. Although, way back then, it was more likely these ancient tape measures were made from sturdy wood.

"Chalk is not the most suitable material for manufacturing measuring equipment and it is thought that the drums may be replicas of original 'working' standards carved out of wood. However, wood is not preserved on most Neolithic archaeological sites and no wooden measuring devices have been found in prehistoric Britain," explains one of the researchers, Andrew Chamberlain, a bioarchaeologist from the University of Manchester.

"The existence of these measuring devices therefore implies an advanced knowledge in prehistoric Britain of geometry and of the mathematical properties of circles."

This study has been published in the British Journal for the History of Mathematics.