New York City has plenty to worry about from sea level rise. But according to a new study by NASA researchers, it should worry specifically about two major glacier systems in Greenland's northeast and northwest - but not so much about other parts of the vast northern ice sheet.

The research draws on a curious and counter-intuitive insight that sea level researchers have emphasised in recent years: As ocean levels rise around the globe, they will not do so evenly.

Rather, because of the enormous scale of the ice masses that are melting and feeding the oceans, there will be gravitational effects and even subtle effects on the crust and rotation of the Earth.

This, in turn, will leave behind a particular "fingerprint" of sea level rise, depending on when and precisely which parts of Greenland or Antarctica collapse.

Now, Eric Larour, Erik Ivins and Surendra Adhikari of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory have teased out one fascinating implication of this finding: Different cities should fear the collapse of different large glaciers.

"It tells you what is the rate of increase of sea level in that city with respect to the rate of change of ice masses everywhere in the world," Larour said of the new tool his team created.

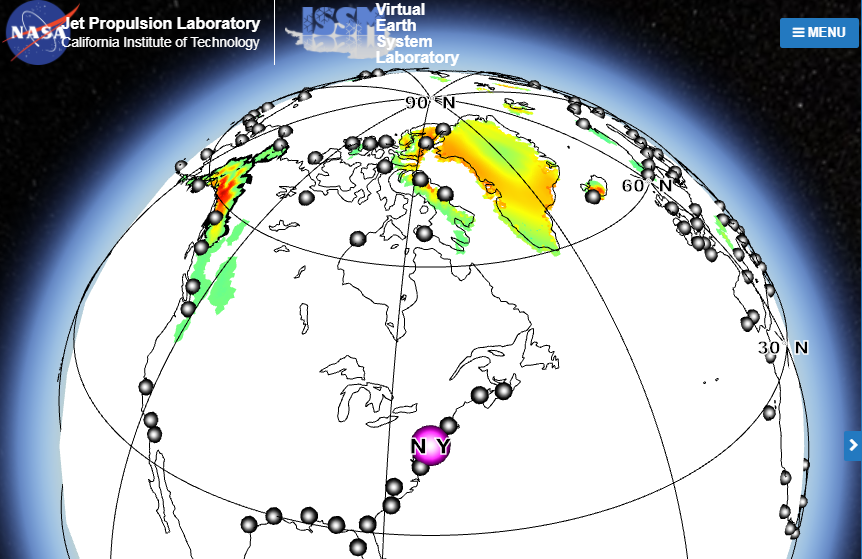

The research was published in Science Advances, accompanied by an online feature that allows you to choose from among 293 coastal cities and see how certain ice masses could affect them if the ice enters the ocean.

The upshot is that New York needs to worry about certain parts of Greenland collapsing, but not so much others.

Sydney, however, needs to worry about the loss of particular sectors of Antarctica - the ones farther away from it - and not so much about the ones nearer. And so on.

Screenshot of the glacier simulation tool (NASA)

Screenshot of the glacier simulation tool (NASA)

This is the case because sea level actually decreases near a large ice body that loses mass, because that mass no longer exerts the same gravitational pull on the ocean, which accordingly shifts farther away.

This means that from a sea level rise perspective, one of the safest things is to live close to a large ice mass that is melting.

"If you are close enough, then the effect of ice loss will be a sea level drop, not sea level rise," said Adhikari. The effect is immediate across the globe.

Indeed, the research shows that for cities like Oslo and Reykjavik, which are close to Greenland, a collapse of many of the ice sheet's key sectors would lower, not raise, the local sea level. (These places have more to fear from ice loss in Antarctica, even though it is much farther away.)

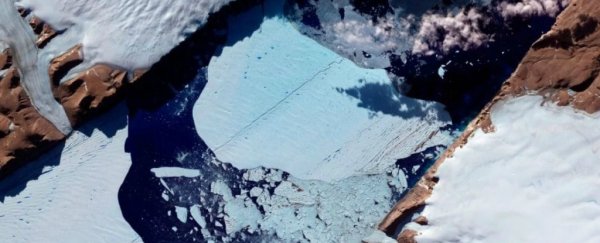

Here's a figure from the researchers showing which parts of Greenland threaten New York the most:

(NASA/JPL-Caltech)

(NASA/JPL-Caltech)As you can see, the risk is mainly from the northern parts of Greenland and especially from the ice sheet's northeast.

This is revealing because while Greenland has hundreds of glaciers, three in particular are known to pose the greatest sea level risk because of their size and, if they collapse, how they could allow the ocean to reach deep into the remaining ice sheet, continually driving more ice loss.

The three most threatening by far are Jakobshavn glacier on Greenland's central western coast, Petermann glacier in its far northwest and Zachariae glacier in the far northeast.

Zachariae is part of a massive feature known as the Northeast Greenland Ice Stream, which reaches all the way to the centre of the ice sheet and through which fully 12 percent of Greenland's total ice flows.

The new research shows that Petermann, and especially the northeast ice stream, are a far bigger threat to New York than Jakobshavn is.

In a high-end global warming scenario run out for 200 years, the study reported, Petermann glacier would cause 3.23 inches (8.2 centimetres) of globally averaged sea level rise, the northeast ice stream would cause 4.17 inches (10.6 centimetres), and Jakobshavn would cause 1.73 inches (4.4 centimetres).

Of this total, New York would see two inches of rise from Petermann, 2.83 inches (7.2 centimetres) from the Northeast ice stream and just 0.6 inches (1.5 centimetres) from Jakobshavn.

This all really matters because in the real world, glaciers are melting at very different rates. Jakobshavn is the biggest ice loser from Greenland and is beating a very rapid retreat at the moment.

Zachariae is starting to lose ice and looking increasingly worrisome, but still nothing like Jakobshavn. Petermann is holding up the best, for now, though it has lost large parts of the floating ice shelf that stabilises it and holds it in place.

You will note that in no case does New York get the full effect of ice loss from any of these parts of Greenland - it's still far too close to the ice sheet.

But Miami gets 95 percent of the globe's total sea level rise from the northeast ice stream, while distant Rio de Janeiro gets 124 percent, or over five inches in the scenario above.

The same goes for Antarctica - its melting, too, will have differential effects around the world. And that matters even more because the ice masses that could be lost are considerably larger than in Greenland. Antarctica, like Greenland, is melting at different rates.

Substantial ice loss is already happening in west Antarctica and in the Antarctic peninsula. Meanwhile, although scientists are watching the far larger eastern Antarctica carefully, so far it's not contributing nearly as much to sea level rise.

Farther away - like, say, New York - Antarctic loss is a big deal. Research has shown that if west Antarctica collapses, the US East Coast would see more than the average global sea level rise.

The research represents a new departure in the science of sea level "fingerprinting", said Riccardo Riva, a researcher who studies sea level at Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands, and who was not involved in the work.

"So far, sea level fingerprints have been used in an ice-centred way, for instance to compute how a given amount of melt from a specific ice source will affect sea level change worldwide," said Riva.

"The authors are reversing the viewpoint, examining how much a certain location is affected by ice melt from different ice sources, and this provides a much better risk assessment by highlighting the ice sources that will have the largest impact."

The current research does not take into account all aspects of sea level rise. Shifting ocean currents can redistribute the mass of the oceans and change sea level, for instance, and as global warming progresses, it causes seawater to expand, and thus a steady rise in seas.

Overall, though, the new study underscores a common theme of recent climate developments: We are now altering the Earth on such a massive scale that it puts us at the mercy of fundamental laws of physics as they mete out the consequences.

2017 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.