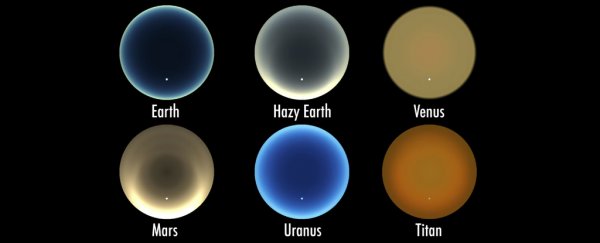

How would the Sun look as it dipped below the horizon on a long (17 hour) day on Uranus? Or what would a late-night sunset on Mars look like, when we finally get there? Thanks to some NASA computer modelling, these scenarios are now a little easier to imagine.

What makes a sunset is the interplay of light from the Sun – which includes all the colours of the rainbow – together with the gases and dust in the atmosphere. The less atmosphere, the less impressive the sunset.

Planetary scientist Geronimo Villanueva, from NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, has created simulations of how sunsets might look on Venus, Mars, Uranus, the Saturn moon Titan, and Trappist-1e.

The shows are quite spectacular, as you can see below, with scenes shown as if you were pointing a camera with a super-wide lens up at the sky.

On Venus, for example, a bright yellow fades down into orange, brown, and then black as the Sun disappears. Since the planet rotates on its axis so slowly, you'd need to wait around 116 times as long as you would on Earth, which is a little more than half of a Venusian year.

Not that you'd necessarily be settling down to watch the sunset on Venus, what with its thick, CO2-heavy atmosphere, intense surface pressure, and average temperatures of 471 degrees Celsius (880 degrees Fahrenheit).

These simulations aren't just fun to watch. They have a serious scientific point to them, too - preparations ahead of a potential probe mission to Uranus. There's still a lot we don't know about the gas planet, and any readings of its atmosphere would need to interpret the levels of light reaching the spacecraft's sensors.

With data from this simulation on board, the probe would have a better idea of what it was looking for, and could better assess the composition of the atmosphere as it absorbed sunlight – which wavelengths were being scattered, and by what.

Here's another look at the beautiful sunset models:

The new models are now a part of the Planetary Spectrum Generator, built by Villanueva and his colleagues, which is used to interpret light reaching our telescopes, and to decode it to try and understand what the atmosphere is like on other worlds.

Mars is the only other planet we have a realistic chance of living on, unless we're going to spend all our time in an incredibly strong and robust floating spaceship that can resist extremes of pressure and temperature.

Villanueva's simulation shows how the Martian sunset would look to its inhabitants, with the atmosphere creating a mix of muddy brown and bright yellow colours as the Sun disappeared behind the horizon.

In fact, these simulations are only part of the story – as the Curiosity rover has already shown, days on Mars can end with a distinctly blue-ish tinge, as the dust scatters the red wavelengths of light away from view, leaving the blue wavelengths to hit our eyes. If only we could go and see for ourselves.