It's been exactly 500 years since Leonardo da Vinci died, and even after all this time we're still trying to discover new things about the famous Italian polymath.

Two scientists have studied historical accounts of da Vinci's life and come to the conclusion that he had a behavioural condition – attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or ADHD.

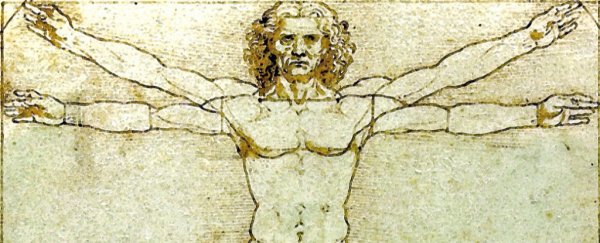

Leonardo da Vinci is widely known for his paintings – especially the iconic Mona Lisa and The Last Supper. But he's also been recognised for his inventive mind: da Vinci's journals and notes are brimming with ideas, including sketches of early versions of a parachute, a helicopter and even a tank.

"The story of Da Vinci is one of a paradox - a great mind that has compassed the wonders of anatomy, natural philosophy and art, but also failed to complete so many projects," neurophysiologist Marco Catani and medical historian Paolo Mazzarello write in a new paper.

"The excessive time dedicated to idea planning and the lack of perseverance seems to have been particularly detrimental to finalise tasks that at first had attracted his enthusiasm."

Catani - who specialises in autism and ADHD - and his colleague argue that the littering of commissioned works that were abandoned, da Vinci's lack of discipline, his weird work hours and lack of sleep could all be symptomatic of ADHD.

"He was left-handed and aged 65 he suffered a severe left hemisphere stroke, which left his language abilities intact. These clinical observations strongly indicate a reverse right-hemisphere dominance for language in Leonardo's brain, which is found in less than 5 percent of the general population," the pair explain in the paper.

"Furthermore, his notebooks show mirror writing and spelling errors that have been considered suggestive of dyslexia. Atypical hemispheric dominance, left-handedness and dyslexia are more prevalent in children with neurodevelopmental conditions, including ADHD."

But while this might be a fun exercise for the 500th death-versary of a 'Universal Genius', it actually highlights something that scientists and historians have been arguing about for decades - retrospective diagnoses.

Retrodiagnoses are exactly what they sound like: an attempt to medically diagnose historical figures long after death.

In a 2014 paper, medical ethicist Osamu Muramoto explained that although doctors and scientists use these retrodiagnoses as a sort-of interesting brain teaser, those in humanities argue that medical professionals don't have the skills to investigate historical sources in their proper context.

"These 'hobbyist' historians are not following the methodological disciplines of historiography, literary criticism, and other relevant subject areas of the humanities and social sciences. For example, they often literally interpret the documents in translation without critically analysing the primary source in the original language," Muramoto wrote in the 2014 paper.

"But more importantly, as these retrospective diagnoses become more and more medically sophisticated as medical knowledge advances, these critics are increasingly skeptical about the authenticity of such highly specific and speculative diagnoses."

That's not to suggest that this paper on da Vinci necessarily falls into the same trap, but it does show it's important to take these types of arguments with a grain of salt.

ADHD is a diagnosis which has only been defined relatively recently, it's tricky to pin down, and it's even harder to spot in adults than children.

Without a time machine, we're not going to find out whether da Vinci's lack of discipline and abandoned projects were symptoms of ADHD. But it does show than even five centuries later, we're still trying to understand da Vinci's incredible mind.

The paper has been published in Brain.