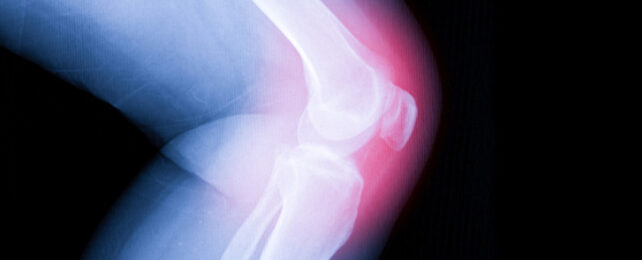

The groans of pain as we get up from the sofa or the sound of crunching cartilage when taking the stairs are all too familiar. Many of us look down at our aching knees and curse them – wondering why they seemingly evolved to hurt so much.

But the human knee has a complex evolutionary history. And new research is showing how misunderstood it is.

The knee has undergone major changes to its size and shape, not only to allow early humans to walk upright, but also to differentiate us (Homo sapiens) from our extinct genetic relatives, such as Homo erectus and Homo neanderthalensis ( Neanderthals).

Natural selection, acting with other evolutionary forces, like random mutation or genetic heritage, probably shaped the knee to help us walk on two legs more efficiently and for longer than our relatives.

Many of the knee problems we face today are new problems our ancestors did not experience. For example, in 2017, research suggested that the sedentary lifestyle of the post-industrial world may have led to a 2.1-fold increase in the rate of knee osteoarthritis, the most common form of arthritis of the knee.

When the researchers studied the remains of hunter gatherers who lived up to 6,000 years ago, they discovered that knee osteoarthritis was probably not a problem at all back then. In the UK today over a third of people over 45 in the UK, have sought treatment for osteoarthritis – primarily for the knee.

Weaker muscles for stabilising and protecting joints and relatively weaker cartilage to cushion the scraping of bones are probably the result of humans moving a lot less than they used to – sitting in an office or running on a treadmill builds less muscle than hunting deer for most of the day in challenging terrain.

For us to evolve osteoarthritis-free knees, sedentary people with "good" knees would need to have more children than sedentary people with "bad" knees for many generations.

But it gets more complicated. The knee is an intricate piece of biological machinery that scientists don't fully understand.

This is particularly the case for sesamoid bones – small bones that are embedded in tendons or ligaments like the kneecap. These bones can be present throughout the mammalian skeleton.

This means some mammals may have sesamoid bones when even members of the same species don't. One such example is the lateral fabella, which is behind the knee and can be found in an average of 36.80 percent of human knees today.

Despite hundreds of years of research, little is understood about sesamoid evolution, growth, development and why they are present in some species and not others. This is so much so that sesamoids are often missing from the articulated skeletons you see in museums, thrown away with the muscles they are embedded in.

New work from my colleagues and I has shown that two of these often misunderstood bones, the medial and lateral fabellae, which are behind the knee, could have evolved in multiple ways in primates and helped early humans learn to walk upright.

The research was a systematic review of three sesamoid bones in 93 different species of primate, including other hominids and common ancestors to humans.

Our work showed that humans have a distinct form of evolution for these bones that may have begun at the origin of hominoids, a group of primates that include apes and humans.

Scientists think that using the existing fabella bone for a new purpose, something called an exaptation, may have helped early humans go from walking on four limbs to two. Interestingly, this bone is also linked to higher rates of osteoarthritis. People who have it are twice as likely to develop the condition. Evolution is not a simple road to biomechanical efficiency.

This picture gets even more complicated when we realise that, unlike teeth, knees are "plastic", meaning they shift and change depending on factors like nutrition and usage. Teeth on the other hand (once grown) don't adapt and simply become damaged. This is why it is so important to exercise as we age – to keep our bones strong.

Knees change and adapt in response to their use, or lack thereof. A global increase in nutrition causing humans to be taller and weigh more is the leading hypothesis as to why fabellae are becoming more common, for example. The presence of the fabella has trebled in the past 100 years or so, with some variation worldwide.

We know that the evolution of the knee in humans hasn't been straightforward, and instead had branching paths. We also know that we are living in a way that our bodies are poorly adapted to, and lifestyle changes are probably the culprit of knee issues that have become more severe with time.

The knee didn't evolve for the age in which we find ourselves and the bone that may have helped us walk in the first place may be part and parcel of those problems.

So, when your knees buckle on the treadmill or feel sore when you're sitting down, spare a thought for them because evolution isn't as easy as it seems.![]()

Michael Berthaume, Reader in the Department of Engineering, King's College London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.