Dreaming is one of the strangest things that happens to us, and for as long as we have been recording history, we have been puzzling over why our minds are so active while we sleep.

Finally, new research claims to have evidence as to what dreaming is all about - and it will probably surprise no one.

According to a team from The Swansea University Sleep Lab in the UK, dreaming really does help us process the memories and emotions we experience during our waking lives.

This is not a new idea at all.

The hypothesis that dreaming was connected to waking life was floated by Sigmund Freud in the early 20th century - he called this phenomenon day residues. Many other studies since have expanded on the notion, indicating that a very real link exists.

But dreams are hard to study, because they take place entirely in the mind of someone unable to communicate in the moment.

Scientists don't have the tools to observe them directly - at least, not yet - instead having to rely on the dreamer's memories of their dreams; and, as we all know, that's not always easy to do.

The team's research, however, seems to have hit upon a winning formula, finding that the emotional intensity of a waking experience can be linked to the intensity of dreaming brain activity, and the content of the dream thereof.

They recruited 20 student volunteers for the study, all of whom were able to recall their dreams frequently.

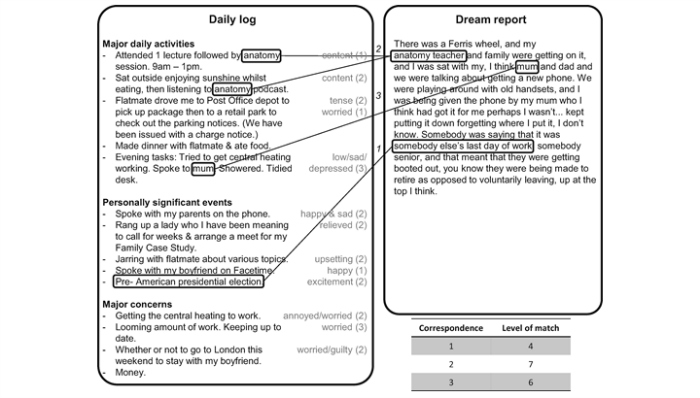

First, they had to make detailed journals of their daily lives for 10 days, logging their major daily activities that took up large blocks of time; personally significant and emotional events; and any concerns that may have been on their minds.

For each of these, the participants had to record how it made them feel, and rate the intensity of that emotion using a numbered scale.

On the evening of the 10th day, they spent the first of several nights in the sleep lab being monitored with non-invasive electroencephalography caps. These were able to observe and record the activity of the brain waves associated with slow-wave sleep (large irregular activity, or LIA) and rapid-eye movement sleep (theta activity).

After 10 minutes of each of these sleep cycles, the researchers would wake the students and ask them what they were dreaming (which sounds like a nightmare, if you ask us). These dreams were then compared with the journals to see if there was any sort of correlation.

(Eichenlaub et al., Social Cognitive & Affective Neuroscience, 2018)

(Eichenlaub et al., Social Cognitive & Affective Neuroscience, 2018)

And here's the paydirt: there was. The number of events recorded in the diaries was linked to the intensity of theta waves - so the more a person had going on in their lives, the more intense their REM sleep - but not their slow-wave sleep.

In addition, dreams that had a higher emotional impact were more likely to be incorporated into the sleeper's dreams than boring, humdrum everyday stuff. And these correlations were only observed for recent experiences, too - there was no correlation between older waking life experiences and dream activity.

"This is the first finding that theta waves are related to dreaming about recent waking life, and the strongest evidence yet that dreaming is related to the processing that the brain is doing of recent memories," psychologist Mark Blagrove of Swansea University told New Scientist.

The next step in the research will be to use binaural beats to induce theta brain waves in sleeping subjects, to see if this in turn induces the sleeper to dream about their recent experiences.

If so, the researchers could have found a method of manipulating REM sleep and theta brain waves to encourage the memory and emotion processing that occur during this sleep phase - a sort of passive form of therapy.

The research was published last month in the journal Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience.