Scientists have uncovered an incredible specimen in Myanmar that has given us a glimpse of life from 100 million years ago - a piece of amber containing the remarkably preserved remains of an ancient bird hatchling.

Inside the amber, you can make out the head, tail, and neck of the bird, but it's the wings and feet that are the real marvels - the chunk of fossilised tree resin has perfectly preserved the bird's feathers, flesh, and claws, and gives us insight into a doomed group of prehistoric species called the 'opposite birds'.

"It's the most complete and detailed view we've ever had," one of the team behind the discovery, Ryan McKellar from the Royal Saskatchewan Museum in Canada, told New Scientist.

"Seeing something this complete is amazing. It's just stunning."

The team suspects that the little bird fell into a pool of conifer sap soon after it hatched, and got trapped in the tar-like liquid.

Interestingly enough, despite being such an important part of our understanding of the prehistoric world, scientists still aren't entirely sure of the exact chemistry at play in the amber preservation process.

Full amber sample. Credit: Lida Xing, Jingmai K. O'Connor, Ryan C. McKellar, Luis M. Chiappe, Kuowei Tseng, Gang Li, Ming Bai

Full amber sample. Credit: Lida Xing, Jingmai K. O'Connor, Ryan C. McKellar, Luis M. Chiappe, Kuowei Tseng, Gang Li, Ming Bai

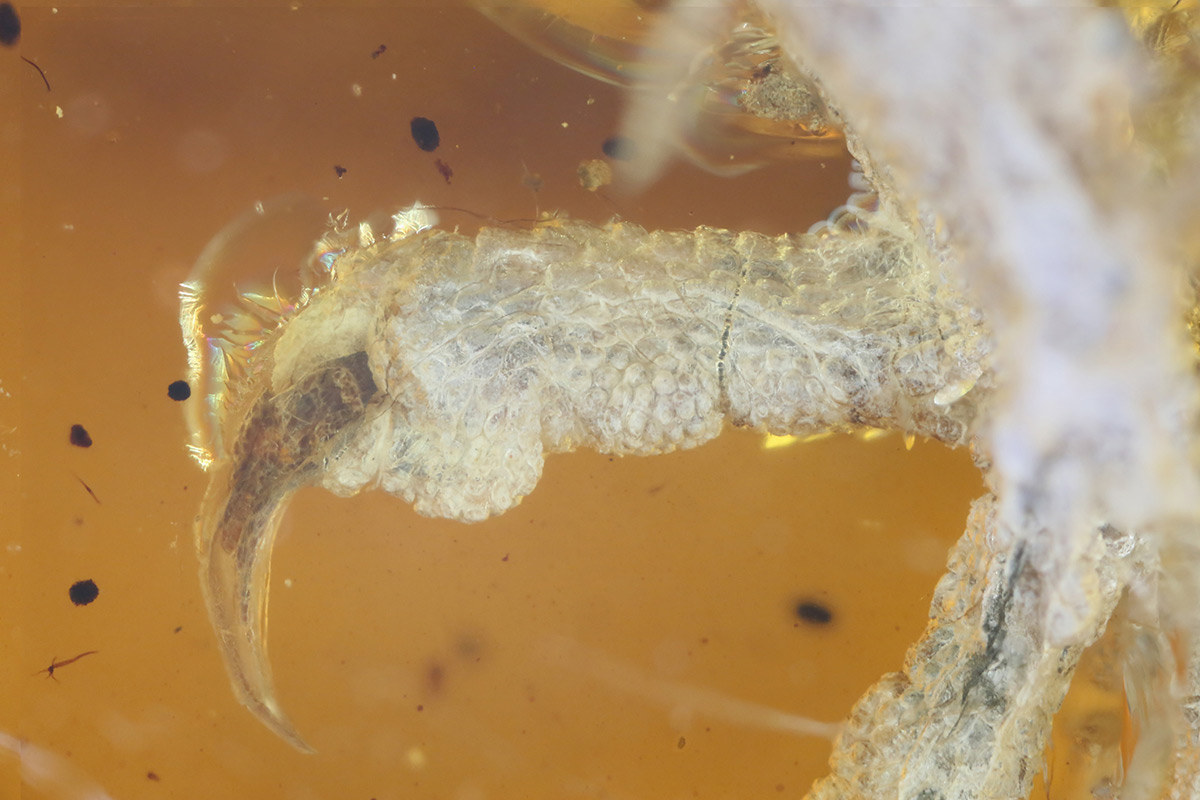

Close-up of the wing. Credit: Ming Bai

Close-up of the wing. Credit: Ming Bai

What we do know is that after animals get stuck in tree resin, it starts to harden, and if you have the right levels of pressure and temperature, it will transform into a semi-fossilised substance called copal.

"The speed of this process varies tremendously depending on the conditions," Brian Palmer explains for The Washington Post.

"Scientists don't agree on when resin officially becomes copal, or when copal officially becomes amber. Some say that amber must be at least 2 million years old, but that cutoff is arbitrary."

Unfortunately, while it looks almost good as new, sitting in that amber, the bird's flesh will have likely broken down into pure carbon, which means its DNA is probably long gone.

But what we can glean from this specimen is the fact that it was probably a member of the so-called opposite birds, or Enantiornithes - a group of prehistoric birds, thought to have evolved at the same time as the ancestors of modern birds, but for some reason died off with the non-avian dinosaurs.

"In appearance, opposite birds likely resembled modern birds, but they had a socket-and-ball joint in their shoulders where modern birds have a ball-and-socket joint - hence the name," Michael Le Page reports for New Scientist.

"They also had claws on their wings, and jaws and teeth rather than beaks - but at the time the hatchling lived, the ancestors of modern birds had not yet evolved beaks either.

You can see the rest of the images of the amber below:

Close-up of foot. Credit: Xing Lida

Close-up of foot. Credit: Xing Lida

Close-up of claw. Credit: Xing Lida

Close-up of claw. Credit: Xing Lida

Reconstruction. Credit: Cheung Chung Tat

Reconstruction. Credit: Cheung Chung Tat

The find has been published in Gondwana Research.