Astrophotography allows us all to become citizens of the cosmos.

At a glimpse, we can be transported into the depths of space to gaze upon Jupiter's dazzling cloudscape. Moments later we can picture the shifting rust-colored sands of Mars, or navigate our way across the lunar surface.

It's a gift that's easy to take for granted. After all, a century and a half ago it took the creative hand of a talented artist to preserve what only a privileged few ever got to see; a hand not unlike Étienne Léopold Trouvelot's.

Born in France in 1827, the lithography printer fled to America with his wife Adele following a coup by Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte in 1851. There, a brief foray into entomology would have devastating consequences for his new home, leading Trouvelot to return to old passions – art and astronomy.

At a time when photography was in its infancy and even the best telescopes were little more than finely crafted lenses, there was no substitute for a generous dose of artistic license when it came to preserving what the eye saw.

"A well-trained eye alone is capable of seizing the delicate details of structure and of configuration of the heavenly bodies, which are liable to be affected, and even rendered invisible, by the slightest changes in our atmosphere," Trouvelot wrote of his work.

Today, his astronomical artworks can still stir up emotions of awe and wonder over the stunning beauty of stars and gas clouds few have the fortune of seeing first hand.

(Étienne Léopold Trouvelot/Public Domain)

(Étienne Léopold Trouvelot/Public Domain)

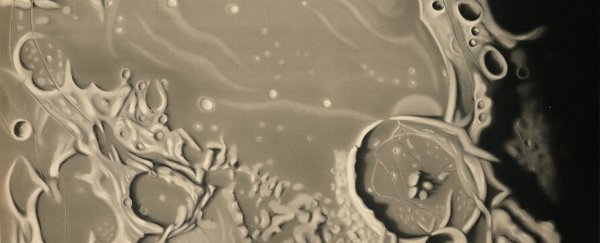

Or his intricate mapping of the texture of a Moon so many of us are familiar with, but rarely see up close.

(Étienne Léopold Trouvelot/Public Domain)

(Étienne Léopold Trouvelot/Public Domain)

Even the most common sight, one of a ghostly river of stars that represents a glimpse of our galaxy from within, is transformed into a bold and majestic scene.

(Étienne Léopold Trouvelot/Public Domain)

(Étienne Léopold Trouvelot/Public Domain)

Yet Trouvelot's legacy is a mixed one, deserving of both our respect as an astronomical visionary and our judgement as an ecological villain.

It's not without irony that a man noted for his perspectives on such distant celestial objects could have made such a short-sighted mistake in his own backyard.

The moth that stripped the East Coast bare

Prior to the 1860s, Lymantria dispar dispar – also known as the European gypsy moth – was exclusively an Old World pest.

Today, it chews its way through thousands of square kilometers of greenery in the north-east of the US each year, putting up to 300 different species of tree and shrub at risk. In the past half a century alone the gypsy moth grub defoliated more than 83 million acres of forest in a range that now extends from the Atlantic coast to the centre of Wisconsin.

For such a tremendous ecological threat, the moth's introduction to the US seems absurdly trivial.

Perhaps to supplement his income producing lithography plates in his new home of Medford, Massachusetts, or maybe as a personal interest, Trouvelot spent his free days breeding silkworms.

What started as a small-time hobby rapidly became an industry-scale enterprise. By the end of the Civil War in 1865, Trouvelot claimed to be feeding a million young silkworms on five acres of woodland in his backyard.

Noticing how readily his livestock of grubs were being gobbled up by the birds, he began to consider ways to breed a more robust, faster-breeding grub. With so many oak trees on his property, his attention turned to a European moth that fed on the tree's foliage, and produced young that wouldn't be so alluring to predators.

(Didier Descouens/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 4.0)

(Didier Descouens/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 4.0)

Precisely how Trouvelot's sample of gypsy moth larvae came to America isn't clear. Nor does it really matter. Critically, some time around 1867, Trouvelot began experimenting with the insect inside his Medford home. And, by at least one account, outside of it.

According to Trouvelot, it was a gust of wind that blew gypsy moth eggs out into the wooded area by his home. According to an investigation by a state ornithologist tasked with extinguishing the glowing embers of a moth infestation, Trouvelot's moths were already outside – under netting secured to an oak tree.

Whoever is right, the error would be a costly one, still causing hundreds of millions of dollars damage annually in the US today.

Trouvelot had already given up his entomological experiments long before the first plagues of moths appeared in Medford in the 1880s, no doubt appreciating the gravity of his error.

From silkworms to Sun spots

Time travelers journeying back to Philadelphia in 1876 would do well to stop off at the Centennial International Exhibition.

The first World's Fair to be officially held in the nation, it featured a variety of technological wonders, from Alexander Graham Bell's telephone and the Wallace-Farmer Electric Dynamo to the copper-plated arm of what would become the Statue of Liberty. There were novel foods, like Heinz Ketchup and Hires Root Beer, and displays on current trends in forestry and agriculture.

And there was a sample of pastel artworks by the lithographer and astronomer E. L. Trouvelot, depicting a handful of astronomical delights.

His method was as simple as it was effective, relying on an etched grid across his field of vision to precisely coordinate the major features of his subject.

Just a few years earlier, Trouvelot's talents had come to the attention of the director of Harvard College Observatory, Joseph Winlock. Winlock invited Trouvelot to join their staff in 1872, where he made good use of their 66 centimeter (26 inch) telescope.

In all, Trouvelot produced around 7,000 illustrations based on his observations.

Some are intricate recordings reflecting an age when we were barely starting to comprehend features of planets in our own neighborhood.

(Étienne Léopold Trouvelot/Public Domain)

(Étienne Léopold Trouvelot/Public Domain)

(Étienne Léopold Trouvelot/Public Domain)

(Étienne Léopold Trouvelot/Public Domain)

(Étienne Léopold Trouvelot/Public Domain)

(Étienne Léopold Trouvelot/Public Domain)

Something as familiar as an eclipse takes on an eerie new beauty seen through another's eyes.

(Étienne Léopold Trouvelot/Public Domain)

(Étienne Léopold Trouvelot/Public Domain)

(Étienne Léopold Trouvelot/Public Domain)

(Étienne Léopold Trouvelot/Public Domain)

Others were discoveries attributed to Trouvelot in their own right, such as these 'veiled' Sun-spots which he describes "appear as if seen through a fog, or veil, between the granulations of the solar surface."

(Étienne Léopold Trouvelot/Public Domain)

(Étienne Léopold Trouvelot/Public Domain)

A drawing of the Leonid meteor shower drawn in 1868, long before his time at Harvard, has meteors curving and dog-legging at odd angles across the sky.

(Étienne Léopold Trouvelot/Public Domain)

(Étienne Léopold Trouvelot/Public Domain)

According to 'The Bad Astronomer' Phil Plait, it's a mystery why he drew it this way.

"It's possible he was seeing persistent trains, the glowing vaporized rock from the meteoroid that can last for several minutes," Plait told ScienceAlert.

"High-level winds can blow those into weird and twisted shapes, consistent with what he drew. That takes time, so the fact that he drew a bright head on them may have been a bit of artistic interpretation."

Modern photography captures in an instant what an artist in another time would take time to contemplate. While we can only guess at Trouvelot's inspiration, it's small details like these that preserve a perspective over objective observations.

In 1882, Trouvelot's major works and scientific writings would be published by Charles Scribner's Sons as The Trouvelot Astronomical Drawings Manual. It would also be the year Trouvelot would return to France, to quietly live out his last years.

The history of science is full of inspiring stories and cautionary tales. Yet it's rare to find them both sitting so closely side-by-side in the same biography, as we do with Étienne Léopold Trouvelot.