When we study ancient societies, it can sometimes be difficult to tell who fulfilled which of the various day-to-day roles. For Ancient Egypt, we have a wealth of information, including pictorial records along with sculptures and figurines, buried with the deceased so they could have workers in the afterlife.

But these depictions can be idealised, or leave things out. Bones, on the other hand, don't lie - and the teeth of an Egyptian woman who lived over 4,000 years ago show that the lives of women back then may have been more varied than some records suggest.

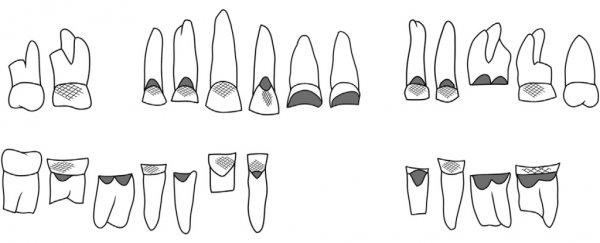

Two patterns of wear on 16 of her 24 teeth are inconsistent with eating, which means she was using her teeth for something else; further analysis suggests she was a craftswoman.

This, according to a research team from the University of Alberta, is a surprise.

"Based on tomb paintings and recovered texts, scholars assert that there were only seven professions open to women throughout ancient Egyptian culture history," they wrote in a new paper.

"[Those are] as priestesses in temples dedicated to goddesses (for high status and well-connected women); as singers, musicians, and dancers (for women with skills and talent); as mourners; as weavers of cloth in the workshops of the aristocracy; and as midwives."

The remains, originally excavated in the 1970s, are from a necropolis in Mendes, which was once the capital of Ancient Egypt. The woman lived around 2181-2055 BCE, and died after the age of 50.

Apparently she was well respected, too, compared to other remains dating from the same era. She was placed in a wooden coffin lined with reeds, with grave goods that contained alabaster vessels, a bronze mirror, cosmetics and gold leaf.

And, of the roughly 1,070 total teeth from the necropolis site that survived the millennia and excavation of their 92 skeletons, only hers showed these unusual wear patterns.

Incisor wear. (Lovell & Palichuk, Bioarchaeology of Marginalized People, 2019)

Incisor wear. (Lovell & Palichuk, Bioarchaeology of Marginalized People, 2019)

Scanning electron microscopy and micrography were used to examine the teeth in detail. Her two central maxillary incisors had severe wear in a wedge-shape, and 14 teeth had flat abrasions.

The wedge-shaped wear, the researchers believe, is consistent with wear seen in teeth from other cultures around the world, where craftspeople split plant material such as reeds by using their teeth.

"A strong case can be made that the plant was Cyperus papyrus, an aquatic sedge that grew abundantly in the delta," the researchers wrote in their paper. "Papyrus stalks were used for firewood, to make boxes and baskets for storage and transport of goods, and to make sandals, curtains, and floor mats."

The outer rind of the stalk was peeled off to use for these purposes, and the inner pith split to make paper. If a craftsperson was using their teeth to split papyrus, this could create significant wear - particularly since papyrus contains silica phytoliths, which would contribute to the abrasion.

So what were the other marks? "It is clear from the SEM images that the vestibular abrasion was the result of a horizontal or side-to-side motion, and the similar appearance of wear on the crown, CEJ, and root suggest that they were caused by the same activity," the researchers wrote.

In other words, it's possible our craftsperson was probably taking care of her teeth by brushing.

(Lovell & Palichuk, Bioarchaeology of Marginalized People, 2019)

(Lovell & Palichuk, Bioarchaeology of Marginalized People, 2019)

Now, we don't know how down with dental hygiene the ancient Egyptians actually were, but evidence suggests "not very". Based on the remains that have been examined over the years, there was a high incidence of plaque, periodontal disease, and tooth loss.

In addition, again, of the 1,070 teeth from that burial site, only the woman's teeth showed signs of this sort of wear.

"It may be the case that plant residues adhered to this woman's teeth as a result of her task activities, necessitating regular cleaning," the researchers wrote.

"Alternatively the abrasion patches may result from the regular application of an analgesic to soothe sore gums… chronic dental pain may have plagued this woman if she persistently used her teeth in task activities."

It seems those tiny mouth-bones can reveal many secrets. Just last year, a Medieval skeleton pulled from the Thames was tentatively identified as a fisherman or sailor because of wear on his teeth consistent with holding a rope. And isotope analysis of tooth enamel can reveal what people ate - even as far back as the Palaeolithic.

Take care of your chompers, folks. It's for posterity.

The new research has been published in Bioarchaeology of Marginalized People.