A recently discovered inscription on an ancient ivory comb is claimed to be the earliest example of a sentence written using an alphabet that would eventually evolve into the set of 26 letters you're translating into words right now.

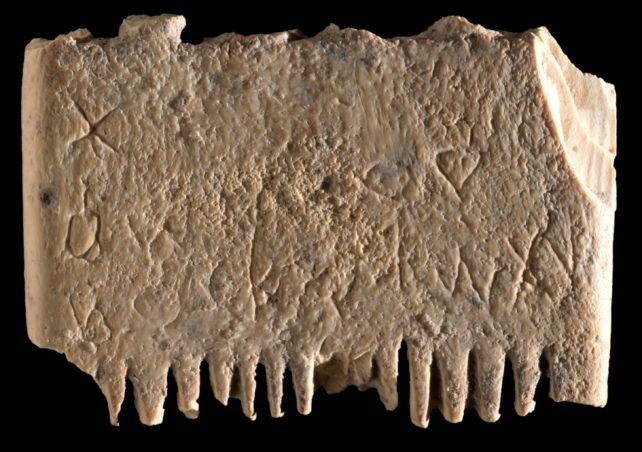

The fine-toothed instrument was unearthed several years ago in Tel Lachish, an old Canaanite city in the foothills of central Israel, but scientists only recently noticed the implement was engraved with 17 tiny letters.

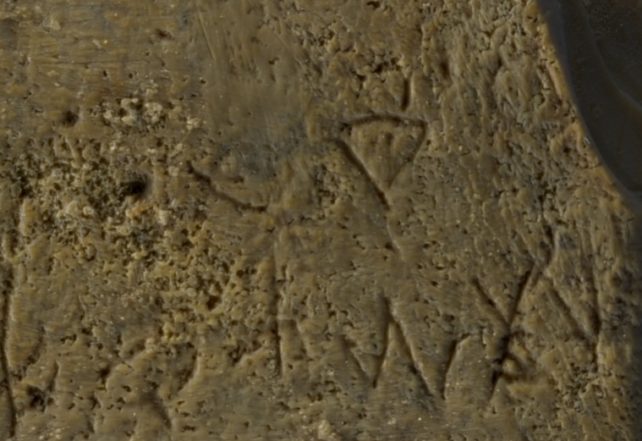

Together, the barely discernible markings form seven separate words, "ytš ḥṭ ḏ lqml śʿ[r w]zqt", which roughly translates to "May this tusk root out the lice of the hai[r and the] beard".

The hopeful message, thought to have been written around 1700 BCE, is the first reliable sentence archaeologists have found in a Canaanite dialect.

That's a big deal because the Canaanite script (aka the Phoenician alphabet) is the earliest known example of an alphabet, one that would be adapted and adopted by cultures all over the globe.

Most modern alphabets now stem from these original, ancient letters, including Arabic, Greek, Hebrew, Latin, and Russian.

Though the pictograms that form the basis of modern Chinese writing go back 5,000 years or so, the system of radicals and symbols that make up its characters don't necessarily contribute to a phonetic foundation of words in quite the same way.

And while there are numerous other examples of isolated letters representing this early Canaanite writing, none have been strung into something legible and meaningful.

"This is the first sentence ever found in the Canaanite language in Israel," explains archaeologist Yosef Garfinkel from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in Israel.

"There are Canaanites in Ugarit in Syria, but they write in a different script, not the alphabet that is used till today…. The comb inscription is direct evidence for the use of the alphabet in daily activities some 3,700 years ago. This is a landmark in the history of the human ability to write."

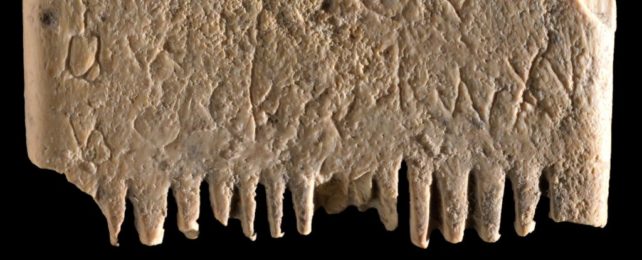

The comb itself is made from elephant tusk ivory and is only 3.66 centimeters (1.4 inches) long and 2.51 centimeters (1 inch) wide.

The shallow inscription on its body is even smaller. Some letters are no larger than a single millimeter. Others have faded to the point where they are practically illegible, making them hard to interpret without their neighbors for context.

One side of the comb contains the remnants of six large teeth, probably for brushing hair, while the other side shows remnants of 14 fine teeth, most likely for removing lice and their eggs.

On the finer side of the comb, a tooth was actually found to contain the hard exterior of a head louse from long, long ago (below). This isn't the oldest evidence of head lice ever found – some samples found in human hair date back at least 10,000 years – but it does suggest that even wealthy Canaanites were irritated by these creepy crawlies.

The ivory used to make the comb was most likely imported from elephants in Egypt, suggesting the material was destined for someone rich enough to afford a foreign luxury. The findings suggest head lice plagued even the wealthy classes of ancient Jerusalem – so much so that a special comb was fashioned for their eradication.

Other examples of curses and hexes written in Canaanite letters have been found adorning more recent artifacts dating between 1200 and 1400 BCE. In fact, similar enchanting inscriptions have been found on a jar from the same dig site as the comb, also dated to a more recent period.

The inscription on the comb is launched at a lowly parasite and was probably written several centuries earlier than other examples.

Radiometric dating of the ancient comb was ultimately unsuccessful, but based on other artifacts previously found in the same area researchers suspect the tool was inscribed in the Bronze Age, about 3,700 years ago.

And judging from the style of the archaic letters, experts think the actual words were written in the "very earliest stage of the alphabet's development", not long after the Canaanite alphabet came to be.

Once humans had a written language, it didn't take long for us to start jinxing just about anything that bothered us.

The study was published in the Jerusalem Journal of Archaeology.