A close look at a mix of old and newly discovered fossils indicates that an ancient species of photosynthesizing bacterium was among the first of its kind to make its home on dry land more than 400 million years ago.

Characteristics of a microbe named Langiella scourfieldii place it into a category of cyanobacteria that would have lived, and thrived, among some of the first plants to grow on land, as well as in bodies of freshwater and hot springs as similar species still do today.

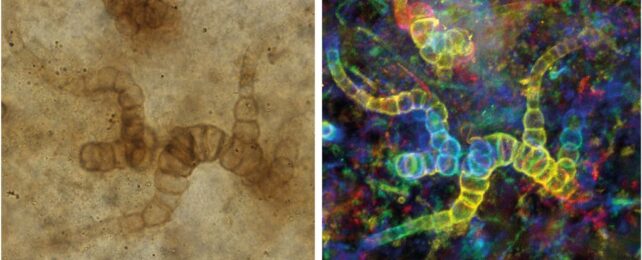

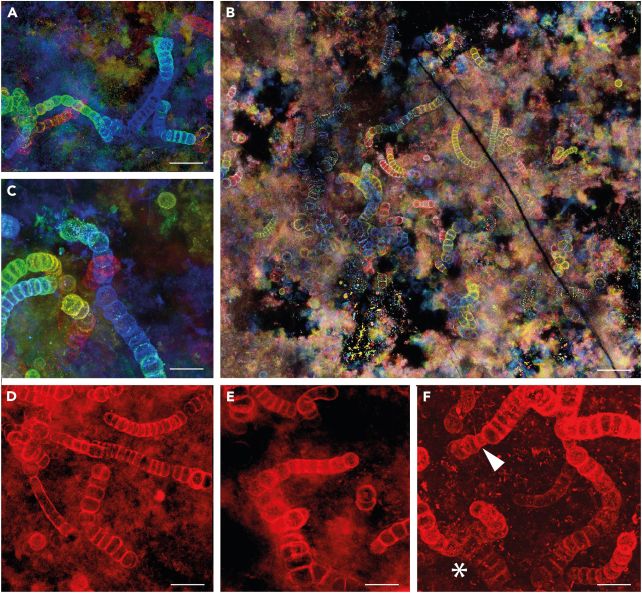

"With the 3D reconstructions, we were able to see evidence of branching, which is a characteristic of Hapalosiphonacean cyanobacteria," says paleobiologist Christine Strullu-Derrien of the National History Museum in the UK.

"This is exciting because it means that these are the earliest cyanobacteria of this type found on land."

The discovery was made in flakes of rock representing the world's earliest known preserved terrestrial ecosystem, the Rhynie cherts in Scotland. While a diversity of life forms have been identified in the 407 million year old fossil beds, the role of cyanobacteria hasn't been clear.

Also known as blue-green algae (even though they are not actually algae), cyanobacteria are marvelous things. They're pretty crucial to life as we know it today, having played a key role in changing Earth into the hospitable environment it is today, some 2.4 billion years ago. As they began to proliferate in Earth's waters, they pumped the air full of oxygen in what's known as the Great Oxidation Event.

Whether you consider this a good thing or a bad thing depends where you are in Earth's history. From our happy, current, oxygen-breathing point of view, it's great. For all the other life that had adapted to Earth in low-oxygen conditions, it was pretty devastating. Mass extinction-levels of devastating.

But cyanobacteria, which can be found thriving around the world today, didn't care. The photosynthetic microbes just kept on keeping on, inserting themselves into whatever ecological circumstances would take them.

Because they are thought to have originated in freshwater environments, cyanobacteria are assumed to have made the leap from soggy circumstances to life on land pretty easily and early.

But just how it carved out a place for itself is more difficult to figure out. The new results are an important piece of the puzzle.

"Cyanobacteria in the Early Devonian played the same role that they do today," Strullu-Derien says.

"Some organisms use them for food, but they are also important for photosynthesis. We have learnt that they were already present when plants first began colonizing land and may have even competed with them for space."

Langiella scourfieldii was first discovered in 1959, but the specimens were difficult to make out. Since then, however, additional specimens have been discovered, allowing the researchers to conduct a more thorough investigation.

They used super-resolution microscopy and 3D reconstruction on new samples of Langiella scourfieldii to work out how it grew.

They found evidence of a structural characteristic known as true branching, which is when bacteria growing together in a line sometimes double up, resulting in another line branching out. This, the team says, represents evidence that the bacteria inhabited the moist land that ringed hot springs.

Together with other evidence, such as molecular clock analyses, and samples such as a billion-year-old branching specimen discovered in Africa a few years ago, the results suggest that cyanobacteria have a much more intricate evolutionary history than is preserved in the fossil record, the researchers say.

"Despite the emergence of embryophytes as both competitors for space and nutrients and new structural elements in ecosystems of increasing spatial complexity, cyanobacteria continued to thrive both within Rhynie hot springs and in adjacent wetlands as they do today in comparable terrestrial environments," they write.

"Able to colonize rapidly, nostocalean cyanobacteria thrived in flooded surfaces with sedimented plant debris."

The paper has been published in iScience.