Roughly 183 million years ago, a deep-sea vampire squid was so caught up in the present that it became a frozen remnant of the past.

The hungry, eight-armed creature had just gotten its tentacles on two tasty fish when it suddenly suffocated to death. Distracted by its prey, the predator probably sank into a region of oxygen-less water near the bottom of the sea and perished with an empty stomach.

Scientists today are now learning from that one fatal mistake.

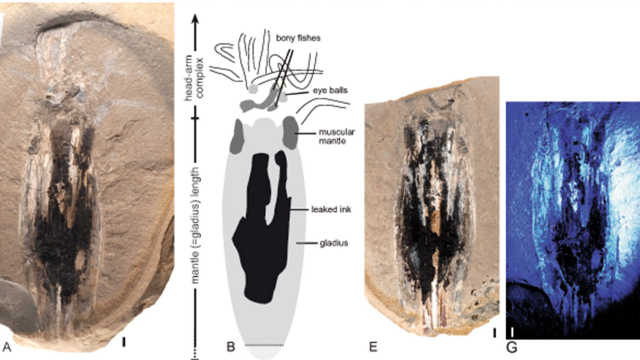

In 2022, a trio of paleobiologists in Germany discovered the vampire squid's fossilized form exceptionally preserved in Jurassic-era limestone located in Bascharage, Luxembourg.

Not only is its last meal clear to see, the 38 centimeter (15 inch) long fossil still contains traces of soft tissue structures, including eyeballs and muscle tissue.

The team says it is a whole new species of extinct vampire squid, and they have called it Simoniteuthis michaelyi.

Despite the colloquial name, vampire squid are not really squid. They are small cephalopods closely related to octopods. And while they do somewhat resemble octopuses, their eight arms are connected by a web of skin that creates a unique, little 'fishing net'.

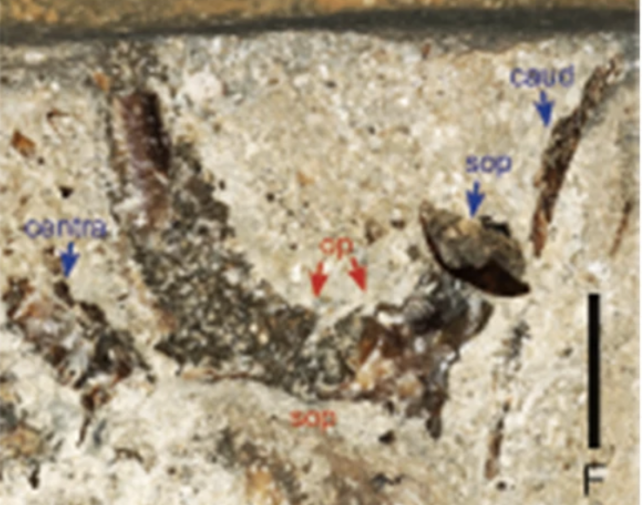

This is where scientists found the remains of two fish in the recently discovered vampire squid fossil, situated tantalizingly close to the mouth between two grayish eyeballs.

Today, there is but one living species of vampire squid left in the deep sea (Vampyroteuthis infernalis), and it kind of looks like a devilish octopus with dark red skin, red eyes, and a webbed skirt of arms.

Long ago, in the Jurassic, however, this single species had a lot more company. Its relatives lived in the shallows and depths of oceans around the world.

The newly discovered extinct vampire squid is somewhat unique among its order. Compared to other 'vampyromorph' fossils found from the Jurassic, including ones unearthed in the same shale deposit near Luxembourg, this one has only eight arms made up of four pairs.

Other extinct vampire fossils usually have five pairs of arms, or at least four with a rudimentary 'fifth pair'.

Without more data, palaeontologists can't say for sure why or when this fifth pair was lost within the order Vampyromorpha, but the newest species could be an important part of the timeline, and the closest analogue yet to its living relatives.

Fossils of this caliber rarely form or survive for long, even under the best of circumstances. To find one in such excellent condition and on the brink of a meal is quite the stroke of luck.

Our fortune today is probably due to the creature's misfortune millions of years ago. Some of the best fossils ever found were formed when oxygen in the oceans was relatively scarce around 183 million years ago. Not only do hypoxic conditions halt decomposition, they also stop corpses from being consumed by other animals.

In this case, when the vampire squid accidentally sank into hypoxic waters, it became buried in a seafloor protected from the decaying force of the elements for tens of millions of years.

And it's not the only vampire squid to meet this fate. It seems that living in the ocean during the warmer Jurassic required creatures to keep their wits about them, making sure to stick to oxygen-rich waters while mating or feeding.

In 2021, fossils belonging to two other ancient vampire squid were found in the United States, having died from suffocation in hypoxic waters after getting caught up in a distracting fight. The ocean's now producing more of these hypoxic ocean zones again as global temperatures rise.

The fossil of S. michaelyi is the first to be found with possible prey in its mouth, revealing the order's eating habits. This is an exceptional find, as most evidence of vampyromorph predation is based on indirect evidence like stomach contents or fossilized poo.

"Although there is fossil evidence of Jurassic vampyromorphs inhabiting deeper waters, at least their earliest representatives more likely roamed and hunted in shallower waters," write the paleobiologists in Germany.

"[S. michaelyi] here confirms that Early Jurassic precursors of the Vampyromorpha were either limited to or had a range including continental shelves."

The study was published in the Swiss Journal of Palaeontology.