A microscopic shape-shifting horror has been seen escaping the confines of our own tiny mobile jail cells in a way nobody predicted.

Like the metal-morphing assassin in Terminator 2, the common fungal pathogen Candida albicans is known to grow a blade-like limb while inside its macrophage captor, which is then used to slowly work itself free.

It was presumed this whole process was accomplished with little more than brute force. New evidence suggests there's a lot more going on than meets the eye.

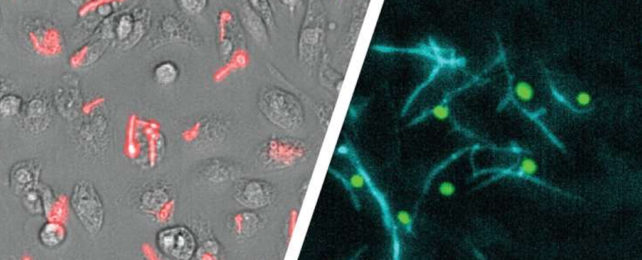

A new automated micro-imaging system allowed Monash University molecular biologist Françios Olivier and colleagues to witness this process in real time in mouse cells to discover these pesky microbes are able to escape mammalian immune systems so thoroughly using a toxic touch.

C. albicans is a common polymorphic fungus that lives within us as a natural part of our microbiome. It can commonly be found happily existing our mouth, digestive, urinary and reproductive organs as a commensal microbe – one that lives within us without causing harm or providing benefit.

Recent studies suggest it may even play a role in balancing our inner ecosystems and even have a protective role by keeping other potential pathogens in check.

Unfortunately, this typically friendly fungus will also seize the chance to become a pathogen if the right conditions arise. It regularly threatens the lives of people with compromised immune systems, like post-surgical and cancer patients.

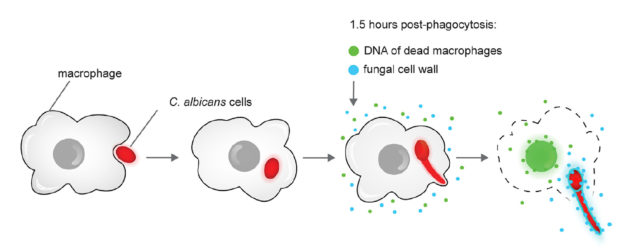

Our bodies recruit immune cells called macrophages to patrol areas of suspicious activity, apprehending suspect disease-causing agents by surrounding and engulfing them. Macrophages will quite readily gobble up out-of-place fungi like C. albicans with the goal of digesting them out of existence.

That isn't always the case, though. Previous studies have revealed the fungal cells are rather talented escape artists, growing elongated sword-like filaments called hyphae to hack their way to freedom.

It now turns out their mighty morphing blade has a talent nobody knew about.

"The initial model posited that the physical force of hyphal growth leads to macrophage membrane damage and hyphal escape," the team write in their paper. "We argue that our data… suggest that hyphal force is not sufficient to drive macrophage escape."

Instead the researchers identified a 'poison' the fungus tips its blade with – two proteins that pierce the macrophage's membrane. These proteins are not expressed in the non-hyphae form of C. albicans.

This escape process busts the immune cell, releasing a whole lot of other chemicals from inside the macrophage as well, triggering a strong immune response that can lead to inflammation processes that cause a lot of cellular carnage.

So targeting the escaping fungus "presents a promising therapeutic avenue, preventing both the spread of the infection and having the potential to dampen inflammation," says Monash University microbiologist Ana Traven.

The team cautions that the full details of this mechanism could vary between fungal strain types. What's more, while there's evidence of this process occurring within humans, the current data was collected from mice macrophages, so more targeted research needs to occur to confirm this process is the same in clinically relevant conditions.

But fungal pathogens are on the rise and can be very difficult to treat and this research has uncovered another potential target.

This research was published in Cell Reports.