If you had to name a creature in the ocean with sharp teeth, you'd probably say "shark", right? I'd be thinking shark. Obviously, the answer is shark.

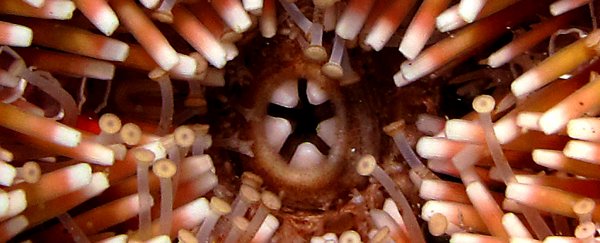

But what about the humble sea urchin? These strange, prickly orbs dwell on the bottom of the seabed and don't even look like they have mouths, let alone teeth. Unless you look closely. Just don't get too close: these critters like to keep their fangs nice and sharp.

In truth, you probably don't have too much to fear from sea urchin teeth, unless you're algae or a sea cucumber. While their spiky spines can give you a nasty sting – and are sometimes venomous – sea urchins don't use their sharp, resilient teeth to bite people.

Sea urchin mouths are located on the underside of their body; to evade predators, they chomp their way into rocks and coral on the seabed, burrowing themselves into cavities to sidestep things like lobsters, eels, and otters.

A sea urchin, with internal jaw apparatus at centre. (Horacio Espinosa)

A sea urchin, with internal jaw apparatus at centre. (Horacio Espinosa)

All that rock-chewing can't be good for teeth, though, so how do sea urchins maintain adequate dental care? Now we know.

In a new study, a team led by mechanical and structural engineer Horacio Espinosa from Northwestern University used electron microscopy techniques to investigate how sea urchin teeth wear away during abrasion processes.

The results confirm an earlier hypothesis at the microscopic level: these teeth sharpen themselves through the abrasion - much like how a blade can be sharpened with a knife sharpener, as material is removed from the cutting edge.

"The material on the outer layer of the tooth exhibits a complex behaviour of plasticity and damage that regulates 'controlled' chipping of the tooth to maintain its sharpness," says Espinosa.

That controlled chipping is pretty different to what happens with human teeth. The outer layer of our teeth is called enamel, and when it's gone, it's gone for good.

A sea urchin's teeth – all five of them, configured in a strange, interlocking five-jaw apparatus – are somewhat different.

When the outer fibrous layer of the teeth, called the 'stone', chips away, it is replaced by new materials that continuously grow underneath. In time, that new layer will become brittle itself and chip away – and so the cycle repeats, fortunately for urchins everywhere.

"Wear-off does not blunt the tip of the tooth, but it instead sharpens it," explains one of the team, graduate student Hoang Nguyen.

"Later, the add-up of new materials, via continuous tooth growth, will compensate for the loss during the animal's life span."

3D scan of sea urchin's five teeth from five separate jaws. (Horacio Espinosa)

3D scan of sea urchin's five teeth from five separate jaws. (Horacio Espinosa)

It's a nifty mechanism, and one that could teach scientists new ways to manufacture materials capable of emulating the unique wearing process of this unusual dental routine – and maybe even lead to the development of "new artificial teeth for humans with superior properties", the researchers suggest.

Pretty impressive really, for a humble sea urchin.

The findings are reported in Matter.