Researchers from the US have developed an electric mouthpiece that can transmit sounds to people with hearing impairments through vibrations on their tongues. And it promises to be cheaper, less invasive and more widely effective than the bionic ear.

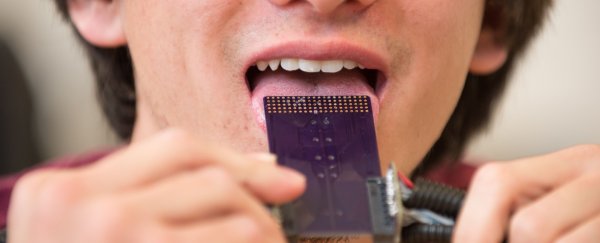

The device uses a Bluetooth-enabled earpiece to pick up sounds, and then converts those sounds into electrical impulses that are delivered in a distinct vibration pattern to an electrode-filled retainer that the users push their tongue up against to "hear".

This is similar to how a cochlear implant, or bionic ear, works, but it doesn't require surgery - with the cochlear implant, electrodes need to be placed onto the patient's cochlear, where they stimulate the auditory nerve with electrical impulses. The new mouthpiece also doesn't require a patient's auditory nerve to be functional, so it will be useable by a whole lot more people with hearing impairments.

"It's much simpler than undergoing surgery and we think it will be a lot less expensive than cochlear implants," said John Williams, a mechanical engineer from Colorado State University, who co-led the project, in a press release.

"Cochlear implants are very effective and have transformed many lives, but not everyone is a candidate. We think our device will be just as effective but will work for many more people and cost less."

Colorado State University

Colorado State University

With training, people with cochlear implants learn to convert the electrical impulses that their auditory nerve receives into sound information. And Williams' team believe that we can do the same thing with our tongues.

Our tongues contain thousands of nerves, and the region of the brain that receives those signals has already proved to be capable of decoding extremely complex information. This means that people can, in theory, be taught to translate vibrations on their tongue into words - effectively allowing them to hear.

What users feel when they push their tongue up against the retainer is just a tingling or vibrating sensation. But their brains can be taught to work out the specific pattern of electrical impulses and translate that into words.

As Mike Hooker, Director of Public Affairs and Communications at Colorado State University, explains in the video below, this is different to teaching a person to read Braille, they wouldn't be feeling the vibrations and then thinking about what word they translate to - their brains would actually learn to do it automatically. Their mouths could seriously learn to hear.

Williams believes that you'd need to wear the mouthpiece, which wouldn't be visible from the outside, for at least two to three weeks, and maybe even up to three months, in order to teach your brain to interpret these signals automatically.

The team is now working with neuroscientists to map the receptors on the tongue and work out which pattern of electrodes on the device will work best. This will give them important information on how consistent people's tongues are - if, generally, all tongues feel electronic impulses in the same regions, then it means they can create one standard device. Otherwise, they may need to tailor each device to the user, which would make things trickier and more expensive.

Unfortunately, it will take a while before the technology can be used by the public, but the team has already started building and testing prototypes (some of which you can see above), and launched a start-up to build the device once the technology is ready.

If all goes to plan, they hope to open up the world of sound to a whole new audience. After all, why should ears get all the fun?