A Vincent Van Gogh scholar has found a document explaining exactly how much of his ear the artist cut off back in 1888.

Not only does the newly found diagram end a longstanding debate over the extent of van Gogh's ear mutilation, it also debunks the myth that he gave his ear to a woman named Rachel, a thought-to-be prostitute.

In case you need a quick refresher, the story goes that van Gogh cut off his own ear on Christmas Eve 1888 in an act of lunacy, wrapped his still bleeding head in a cloth, walked down to a nearby bordello, and gifted the ear to prostitute named Rachel who immediately passed out.

Van Gogh nearly died from the wound, waking in a hospital bed some time later. From there, the story has taken a life of its own with many historians offering different accounts of the incident. Now, after more than century, we might finally know the truth.

The diagram – supposedly created by the physician that treated the wound – was found by Bernadette Murphy from the UK who was researching her new book Van Gogh's Ear, which was published on 12 July and details van Gogh's time in Arles, France, where the notorious incident occurred.

"This investigation has been an incredible adventure and discovering the document was an extraordinary moment," Murphy said. "From my little house in Provence I couldn't believe I had found something new and important about Vincent van Gogh, but it was a vital detail in my complete re-examination of this most famous of artists, the key people he met in Arles and his tragic end."

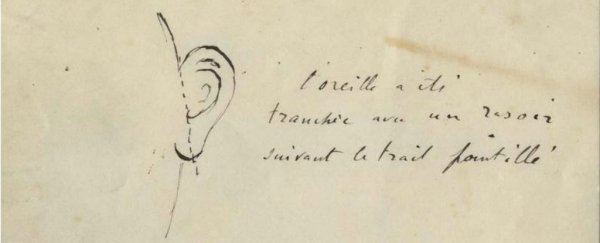

Seen below, the graphic document shows that van Gogh actually cut off most of his ear, leaving only a small part of the lower lobe. This is important because historians have long believed that he only cut off a small piece of his bottom lobe. Now, if the document is to be believed, it was quite the opposite.

Irving Stone Archives/University of California Berkeley

Irving Stone Archives/University of California Berkeley

Murphy first came upon the document in 2010 when she was digging through the Stone archives – a massive collection of documents belonging to Irving Stone, a writer who famously documented van Gogh's self-mutilation in his 1934 novel Lust for Life – at the University of California, Berkeley.

According to Murphy, the illustration was created back in 1930 when Stone went to France in search of Félix Rey, the physician who treated van Gogh's injury. As James Adams reports for The Globe and Mail:

"At some point in their conversation, Stone asked the 65-year-old Rey if he would kindly draw an illustration of van Gogh's injury. The doctor tore off a page from his prescription pad and proceeded to draw, in black ink, a picture of the artist's ear before he attacked it with a cut-throat razor and a picture of it afterward."

This statement is seeming backed up, claims Adams, by the inscription below the illustration where Rey says that he's "happy to give [Stone] the information you have requested concerning my unfortunate friend. I sincerely hope that you won't fail to glorify the genius of this remarkable painter, as he deserves."

While this newly found piece of evidence might have finally solved the debate over van Gogh's ear once and for all, Murphy also says there is another bit of information that's just important: Rachel was actually named Gabrielle and she wasn't a prostitute at all.

According to Murphy, Gabrielle was actually a 19-year-old chambermaid at a brothel where van Gogh frequented. Back in those days, before it was banned after World War II, women over the age of 20 were legally allowed to work as prostitutes, suggesting that Gabrielle was merely an employee of the establishment. The girl also suffered from the long lasting effects of dog bite, leaving her face – and likely part of her ear – disfigured.

So, when van Gogh cut off his ear, he was actually trying to make some kind of a sweet gesture by offering his flesh to her, though there's no way to spin that to make it sound any less creepy.

"There's something semireligious to the way he offers a part of his body to repair a part of her body," Murphy said. "She had a nasty scar on her body, and it's as if he's giving her fresh flesh."

While it's safe to say that van Gogh did suffer from some sort of mental illness – the likes of which are still debated heavily – it's nice to know that researchers are finding missing pieces to the puzzle, helping us understand the mind of one of the most influential artists to ever live.

Hopefully, as more is uncovered, we will eventually know his complete story.

The document will be put on display at the van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam until 25 September.