To step foot inside the Dolmen of Menga is to enter, awed, almost into another world. The ancient building was constructed nearly 6,000 years ago, and stands to this day, perfectly intact, built of stones weighing up to 150 metric tons each.

If you're thinking that such a feat of construction would have required a sophisticated, multidisciplinary understanding of the principles of engineering, you are not wrong.

A new study has found that the Neolithic humans who built Menga were highly skilled, highly knowledgeable, and adept at solving complex engineering problems.

"Initially, what sparked my interest in the Menga dolmen was undoubtedly its monumentality. Entering its interior and contemplating such a colossal monument from the Neolithic period, attracted my curiosity to learn more about this dolmen," geoarchaeologist José Antonio Lozano Rodríguez of the Canary Islands Oceanographic Center in Spain told ScienceAlert.

"They were people with very important knowledge of early science, which indicates how evolved the intellectual, practical and technical capacities of these societies in the south of the Iberian Peninsula were almost 6,000 years ago."

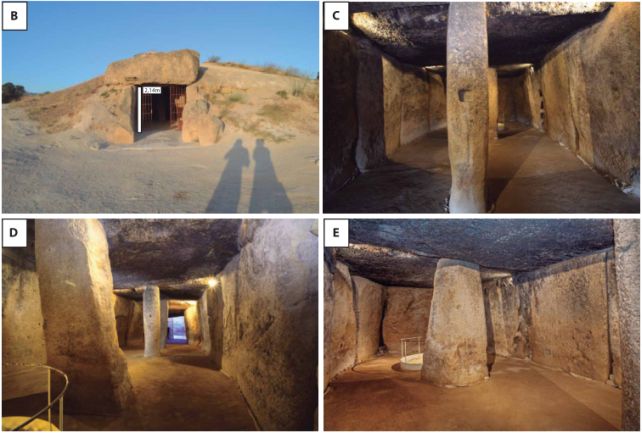

The Dolmen of Menga is, truly, a marvel of the ancient world. Built into the side of an earth mound between around 3800 and 3600 BCE, the large chamber extends 27.5 meters (90 feet), lined – walls and roof – with huge stones.

It's one of the largest megaliths in ancient Europe, and the capstone, weighing an estimated 150 metric tons, one of the largest stones ever moved in Neolithic Europe.

The site's use appears to have been funerary, with grave goods reportedly discovered inside. And it must have been deeply important. Previous analyses have revealed that a great deal of labor was expended to construct it.

Lozano Rodriguez has led previous efforts that determined that not only was the asymmetry of the dolmen's walls intentional, and designed around the solstices, but that the soft rock that went into its construction was sourced from a distance of around 1 kilometer (0.6 miles) from the building site, revealing that the builders knew how to quarry and transport huge chunks of rock.

The Dolmen of Menga's construction consists of a chamber lined and roofed with large stones, with three stone pillars placed along the length of the chamber to support the weight of the roof. The 32 giant stones have a collective weight of around 1,140 metric tons.

To determine how these rocks were placed, and the monument built, Lozano Rodríguez and his colleagues conducted an analysis that encompassed sedimentology, archaeology, paleontology, and petrology.

One of the biggest challenges would be the transportation of the large stones, which, the researchers found, would have required a firm understanding of friction.

The easiest transport method would have been sledges that ran along a pre-built wooden trackway; since the quarry was uphill from the construction site, this would also have required knowledge of acceleration and braking.

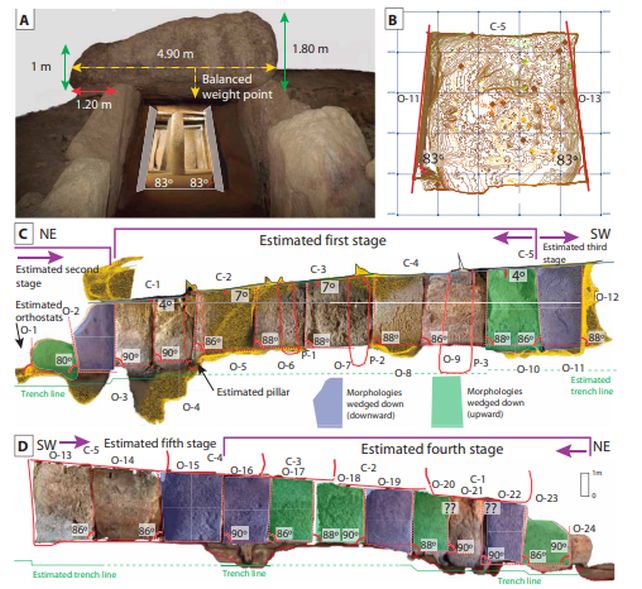

The rocks, they observe, are all classified as "soft" sedimentary, mostly limestone, which would have required careful handling to avoid damage. Nevertheless they have been placed with millimeter precision. They also interlock and lean slightly against each other, which is a clue to the manner and order in which they were placed.

And they are wedged tightly into the bedrock. This is the first time this feature has been observed at Menga in 200 years of study: the foundations of the stones are deep sockets, which would have required careful emplacement that implies the use of counterweights and descending ramps, to carefully slide the stones into position and lever them upright. This deep foundation would also alleviate the need to elevate the roof stones.

The pillar stones were placed in a similar fashion, with deep foundations, but were likely installed after the wall stones. And the wall stones are placed in such a way that their tops lean slightly inwards, resulting in a trapezoidal shape to the chamber, narrower at the top than the bottom. This, the researchers believe, is a stroke of genius, allowing for smaller capstones than would be needed for a wider roof.

"Almost 6,000 years ago they used a relieving arch to solve complex problems of stress distribution, thus solving problems related to weight, which would be one of the biggest structural problems they would encounter in the design of this great monument. This is also solved by using pillars inside," Lozano Rodríguez marvels.

"I was also surprised to see that the monument was designed to be partially buried so that the capstones could be placed without the aid of ascending ramps."

There is no doubt that this ancient, mysterious building has a lot to teach us – not just about building techniques, but also about the ingenuity of Neolithic humans, and the value of an open-minded approach to the abilities of our ancestors.

"The incorporation of advanced knowledge in the fields of geology, physics, geometry, and astronomy shows that Menga represents not only a feat of early engineering but also a substantial step in the advancement of human science, reflecting the accumulation of advanced knowledge," the researchers write in their paper.

"Menga demonstrates the successful attempt to make a colossal monument lasting over thousands of years."

The research has been published in Science Advances.