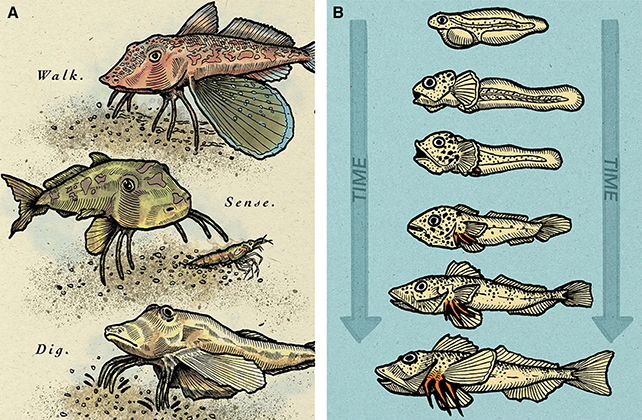

The northern sea robin (Prionotus carolinus) is among the more unusual fish in the ocean, using its leg-like fins to drag itself along the sea floor.

New research reveals these appendages not only aid locomation, but also allow the fish to 'taste' whatever it comes across in the search for food, a discovery that could explain why other marine life follows this fish around, looking for scraps.

This odd game of follow-the-leader is what prompted the international team behind the new research to analyze the northern sea robin more closely, putting captive fish to the test finding buried mussels in lab conditions.

Observations of the captured fish revealed short bouts of swimming and strolling along the tank's sandy floor, with intermittent periods of scratching that gradually uncovered the hidden caches of food. Given none of the control capsules of sea water were found, it seems they had a hidden sense up their sleeve.

The ability of the sea robin to detect and dig out hidden food then led to the discovery that the fish's spindly legs were covered in sensory papillae, which similar to the tiny bumps on our tongues are packed with touch-sensitive taste receptors.

Looking deeper into the animal's genome, the team was also able to find the genes responsible for the development of these special appendages and figure out how the sensory papillae adaptation had evolved in some varieties of the sea robin but not others.

"Sea robins are an example of a species with a very unusual, very novel trait," says Harvard University cell biologist and electrophysiologist Corey Allard. "We wanted to use them as a model to ask, how do you make a new organ?"

The genetic analysis meant the researchers were able to identify the tbx3a gene as key to these sensory leg adaptations. In fish that possed a disfunctional form of the gene, the formation of the legs, papillae, and food scavenging behavior was adversely affected.

Another discovery came when a second delivery of sea robins didn't possess the same ability to taste and dig out food with their legs. It turns out that was because the fish were a different species, Prionotus evolans; a type of sea robin that used their legs to walk, but lacked the sensory capabilities of its relatives.

The researchers found the 'taste-footed' species occur in just a few locations, suggesting the sensory adaptation could be recent in evolutionary terms. What's more, the way these genes are configured is common across limb development in many other species, including humans.

"This is a fish that grew legs using the same genes that contribute to the development of our limbs and then repurposed these legs to find prey using the same genes our tongues use to taste food – pretty wild," says Harvard University cell physiologist Nicholas Bellono.

The team behind the study says the explaination of how such complex traits develop in wild organisms – in this case the sensory limbs of the northern sea robin – can also help in understanding other species, even less well-known ones.

"Although many traits look new, they are usually built from genes and modules that have existed for a long time," says David Kingsley, a developmental biologist from Stanford University. "That's how evolution works: by tinkering with old pieces to build new things."

The research has been published in Current Biology, here and here.