As our planet's permafrosts continue to melt in record-breaking heat, we can expect to find astonishing things from the ancient past.

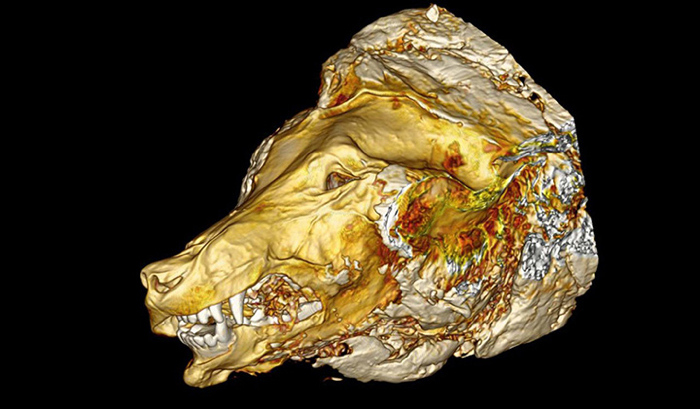

Like this huge wolf head, preserved since the last ice age and unearthed in incredible condition in Siberia in 2018, an estimated 40,000 years since being entombed in frozen wilderness.

The giant head, discovered by a local man in 2018 along the shores of the Tirekhtyakh River in the Russian Republic of Sakha (aka Yakutia), measures a whole 40 centimetres in length (about 16 inches), making it unlike any existing wolf specimen scientists have studied from so long ago.

"This is a unique discovery of the first ever remains of a fully grown Pleistocene wolf with its tissue preserved," palaeontologist Albert Protopopov from the Republic of Sakha Academy of Sciences told The Siberian Times back in 2019.

"We will be comparing it to modern-day wolves to understand how the species has evolved and to reconstruct its appearance."

(Albert Protopopov)

(Albert Protopopov)

The find followed the discovery of a number of ancient cave lion cubs in the same region in 2015 and 2017, and represents another amazingly well-preserved animal recovered from Yakutia: its fur, fangs, skin tissue, and even brain tissue are still seemingly intact.

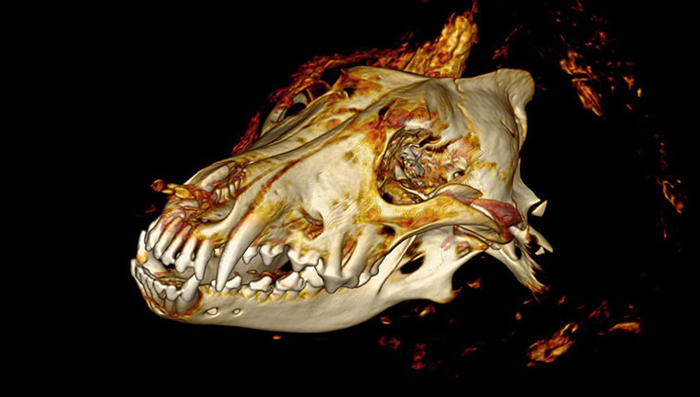

Protopopov, together with scientists from Sweden and Japan, have studied the head, believed to be from an adult wolf two to four years old.

Their work included analysing the ancient animal's DNA, and using tomographic techniques to non-invasively see inside the skull.

(Naoki Suzuki)

(Naoki Suzuki)

According to Protopopov, finding wolf skulls in thawing Siberian permafrost isn't uncommon, but they're rarely on the same level as this massive, ancient predator.

"Several puppies have already been found," Protopopov told Russia's Interfax news agency.

"The uniqueness of this find is that we found the head of an adult wolf with perfectly preserved soft tissues and brain."

(Naoki Suzuki)

(Naoki Suzuki)

Alongside the wolf, the scientists also examined a newly discovered cave lion cub, thought to be a female. The researchers think it may have died shortly after being born and then became preserved in ice.

Nicknamed Spartak, the cub was also in an incredibly undamaged state, giving scientists an amazing opportunity to study and learn more about these ancient specimens.

"Their muscles, organs and brains are in good condition," palaeontologist Naoki Suzuki from the Jikei University School of Medicine in Tokyo told The Asahi Shimbun.

"We want to assess their physical capabilities and ecology by comparing them with lions and wolves of today."

A version of this story was first published in June 2019.