A HIV drug appears to be able to help the brain clear out toxic proteins that lead to Huntington's disease and a type of dementia, raising the possibility it could be repurposed as a therapy for neurodegenerative disorders.

Build up of these protein clusters is linked to cognitive decline – but research in mice showed that existing antiretroviral medication maraviroc can restore the brain's ability to clear them out.

The drug, which is also sold under the brand names Selzentry (US) and Celsentri (Europe), showed signs of reducing brain cell death and slowing down memory loss in mice genetically engineered to have dementia.

It's far too early to say whether the drug can actually help prevent dementia or Huntington's in mice, not to mention humans, but perhaps what's most exciting about the research is that it identifies a biological pathway that leads to neurodegeneration – and a potential way to stop it.

"Maraviroc may not itself turn out to be the magic bullet, but it shows a possible way forward," says neuroscientist David Rubinsztein from the UK Dementia Research Institute at the University of Cambridge, who led the research.

"During the development of this drug as a HIV treatment, there were a number of other candidates that failed along the way because they were not effective against HIV. We may find that one of these works effectively in humans to prevent neurodegenerative diseases."

What's even cooler is that earlier this week another team of researchers found evidence that a common sleeping pill could reduce the build up of similar toxic proteins related to Alzheimer's disease in humans. While it's still very early stages for both of these drugs, it's promising to have two new possible pathways that lead to neurodegeneration for scientists to investigate.

In this latest study, the Cambridge researchers used two strains of mice genetically engineered to experience either Huntington's disease – triggered by clusters of misfolded Huntington proteins building up in the brain – or a form of dementia known as tauopathy that's linked to the build-up of tau proteins.

Similarly, Alzheimer's disease is associated with a build up of amyloid-beta and tau clusters.

In neurodegenerative conditions like these, a build-up of toxic protein clumps is associated with the break down and eventual death of healthy brain cells, which leads to symptoms such as memory loss, confusion, mood swings – and eventually death.

Usually, the body would get rid of these toxic proteins through a process known as autophagy, where cells in the brain would consume any unwanted or toxic proteins, break them down, and remove them. But for some reason, in patients with neurodegenerative conditions, this process fails.

Using the genetically engineered mice, the Cambridge team were able to identify a process that causes autophagy to fail in both Huntington's and tau-related dementia – and then, promisingly, restore it.

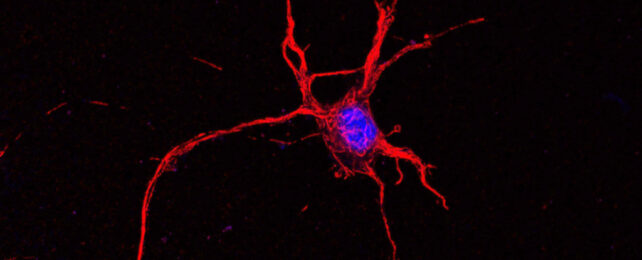

What they found was that, in these genetically engineered mice, immune cells in the brain called microglia became 'activated' to release a set of molecules. These molecules then switch on a receptor located on the outside of neurons called CCR5.

Once CCR5 is switched on, it stops autophagy from occurring. This causes the toxic protein clusters to build up, and these protein aggregates in turn create a positive feedback loop that leads to the activation of even more CCR5 receptors.

To test ways of preventing this loop from occuring, the researchers bred a special strain of 'knockout' mice that had CCR5 deactivated. These mice appeared to be protected from buildups of the misfolded proteins – when compared to control mice, they had fewer toxic clusters in their brains.

The interesting thing is that CCR5 isn't just involved in neurodegenerative conditions, the receptor is also used by HIV as a way to gain entry into our cells. Which is why the researchers decided to test maraviroc.

Mice that were genetically engineered to have Huntington's were given the drug at two months old for four weeks. At the end of the treatment period, the researchers showed they had significantly less build up of misfolded huntingtin clusters in their brains compared to the untreated mice.

However, even untreated mice don't show physical symptoms of Huntington's until at least 3 months old, so the study wasn't able to show whether the drug could reduce symptoms as yet.

But the team also gave maraviroc to mice engineered to have tau-related dementia triggered, and in this case they could show that not only did the drug reduce the build-up of protein clusters, but it also reduced the loss of brain cells.

The mice that had been given maraviroc also performed better than untreated mice at object recognition tests, suggesting the drug may have slowed down memory loss.

"We're very excited about these findings because we've not just found a new mechanism of how our microglia hasten neurodegeneration, we've also shown this can be interrupted, potentially even with an existing, safe treatment," says Rubinsztein.

The research also provides new insight into the roots of neurodegeneration.

"The microglia begin releasing these chemicals long before any physical signs of the disease are apparent," he adds.

"This suggests – much as we expected – that if we're going to find effective treatments for diseases such as Huntington's and dementia, these treatments will need to begin before an individual begins showing symptoms."

The research has been published in Neuron.