In the early 1930s, Dutch anthropologists found a giant bed of bones hidden above the banks of the Solo river on the Indonesian island of Java.

More than 25,000 fossil specimens were buried in the river mud in an area called Ngandong, including 12 skull caps and two leg bones from a particularly intriguing human ancestor: Homo erectus.

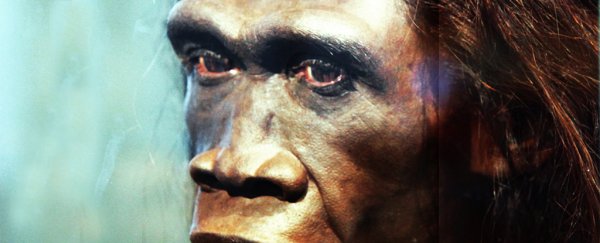

This species of early human persisted for nearly 2 million years and spread far across parts of Africa and Asia. But scientists had been unable to identify when the last of them died out.

Efforts to determine the exact age of the Java fossils didn't help much, since that gave a broad range of options: Their time of death was estimated to be somewhere between 550,000 and 27,000 years ago.

But a study published today in the journal Nature has put questions about the fate of the last H. erectus to rest.

By dating the surrounding river sediment, rather than the fossils themselves, anthropologists were able to identify a much tighter age range for these skulls. The results showed that the H. erectus individuals perished in a mass death between 117,000 and 108,000 years ago.

That means the bones represent the last known appearance of H. erectus in the archaeological record.

The new timeline helps solve other puzzles as well, since it enables anthropologists to identify other ancient human species that H. erectus overlapped with – and those it didn't.

"Our research shows that Homo erectus did not survive late enough to interact with modern humans on Java," Russell Ciochon, a co-author of the new study, told Business Insider. "Ngandong is the youngest known Homo erectus site in the world."

A flood collected the fossilized bones

According to the study authors, the skulls caps and leg bones discovered in Ngandong represent the largest H. erectus find at any single site.

That's because the bones, along with 25,000 other fossils that were later lost during World War II, "accumulated within a log jam in the river," according to study co-author Kira Westaway.

Excavations in Ngandong, Indonesia in 2010. (Russell L. Ciochon/University of Iowa)

Excavations in Ngandong, Indonesia in 2010. (Russell L. Ciochon/University of Iowa)

She added that the skull caps are missing parts of the cranium because the skeletons got damaged when they were washed down the river in a flood. Alongside the fossils, researchers found bones from at least 64 mammals that also got carried downstream.

"The fossils would not have been concentrated in this small area without the flooding event," Ciochon added.

The fact that the bones were all swept downstream at the same time suggests the 12 H. erectus individuals they came from died simultaneously in what could be a mass death.

Climate change may have killed Homo erectus

Ciochon said his team isn't sure how these particular individuals died, but one theory about why H. erectus died out on Java overall may sound familiar: climate change.

Between about 120,000 and 110,000 years ago, the world shifted from a glacial period to an interglacial period, and temperatures rose. Java, which is now mostly rainforest, used to be covered in woodlands.

But around the time of H. erectus' extinction, the island's environment started to get wetter and more humid due to increasing temperatures, which allowed the rainforest to grow.

It's possible our human ancestors there couldn't handle the shift.

"The demise of Homo erectus on Java coincides with this rainforest expansion, and the changing environment likely contributed to the demise," Ciochon said. "No Homo erectus fossils are found after the environment changed, so Homo erectus likely was unable to adapt to this new rainforest environment."

Westaway said the encroaching rainforest "would have caused problems for the essentially open woodland fauna" that H. erectus liked to hunt, which may have led to food insecurity.

"They might not have been able to find food sources they normally ate, or they might have been more vulnerable to the predators in the rainforest," Ciochon added.

The Ngandong site also included bones from animals that were more suited to woodland environments, like elephant, deer, and cattle. Those creatures lived and died at the same time as H. erectus.

Intermingling human ancestors

By correctly dating these fossils, anthropologists can now explore who H. erectus might have interacted with before they died out. The list is large: H. erectus could have interbred with Denisovans – another group of human ancestors found mostly in Siberia and east Asia – as well as two other early human species that lived on Pacific islands, called H. floresiensis and H. luzonensis.

Denisovans lived between 200,000 and 50,000 years ago. Genetic evidence indicates that they interbred with both modern humans and an older species, passing on about 1 percent of their DNA.

"This older species is likely Homo erectus," Ciochon said, given that the new date from his new study falls solidly within the time frame that Denisovans were alive.

But it's not clear whether Denisovans and H. erectus intermixed on Java in particular.

"There is considerable speculation about where and when the Denisovans meet H. erectus and what the results of those interactions were," Ciochon added.

This new discovery also opens up the possibility that the two other east Asian ancestor species descended from H. erectus.

More than 50,000 years ago, H. luzonensis lived and thrived on what's now the Philippine island of Luzon. On the nearby Indonesian island of Flores, H. floresiensis, nicknamed "the Hobbit" for its short stature, lived between 100,000 and 60,000 year ago.

"There is no doubt" that these three species overlapped temporally, Westaway said.

Ciochon and Westaway's new research cements H. erectus' status as one of the longest-lived early humans. The species lasted about 1.8 million years – roughly six times as long as H. sapiens (us) have existed.

The first H. erectus specimen was discovered in Indonesia in 1891, and fossils have been found across Africa and in China. These ancestors made it to Java and nearby Pacific islands by crossing land bridges when sea levels were low, Ciochon said.

He added that it's possible other H. erectus populations outlived the counterparts found at the Java site.

"Our work provides the age of the last know appearance of H. erectus, but this does not mean that it is the age of extinction," he said. "Small groups of H. erectus may have lived longer without leaving fossil evidence."

This article was originally published by Business Insider.

More from Business Insider: