Communities along America's North Atlantic coast are bracing for yet another exceptional hurricane season.

Not only are tropical cyclones brewing earlier than usual, they are also growing in number and severity as the climate crisis unfolds. This year, it is highly possible that meteorologists will once again run out of pre-selected names for Atlantic tempests.

In fact, experts at the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) have never predicted this many named storms before.

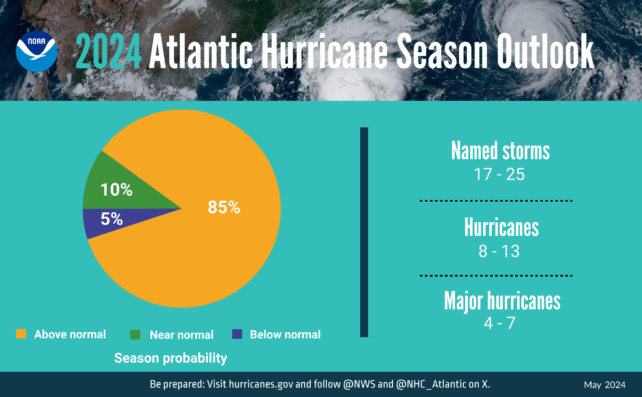

According to available data, the Atlantic hurricane season, which usually runs from June through November with a peak in late summer, has an 85 percent chance of being exceptional.

As many as 25 spinning squalls could be named by the end of the year.

The analysis doesn't predict how many of those ocean-borne storms will make landfall, but the weather patterns unfolding around the world right now have scientists seriously worried.

Ben Kirtman, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Miami, describes the unfolding situation as a "perfect storm".

"We're seeing a shift in climate patterns in the Pacific. El Niño, which tends to increase vertical wind shear in the Atlantic and suppress some hurricane development, is ending," he explains.

"Even though we're transitioning to La Niña conditions in the Pacific, ocean temperatures in the Atlantic are still responding to El Niño and have remained warm. And that's the ideal fuel for hurricanes."

Each year, the World Meteorological Association uses one of six lists of 21 names to be given to tropical cyclones in the Atlantic that feature winds speeds above 63 kilometers per hour (39 miles per hour).

If the gales from these storms breach 119 kph (74 mph), they become categorized as hurricanes. If the winds breach 178 kph (111 mph), a major hurricane is declared in Category 3 to 5.

In both 2020 and 2021, so many cyclones developed in the north Atlantic, scientists ran out of names for them before the season was through.

In 2022, an average number of cyclones were named, but the severity of those squalls was so great, it became the third costliest Atlantic season on record.

The next year was the fourth-most active Atlantic hurricane season on record, and yet fortunately, many of those 2023 storms did not make landfall.

In 2024, we may not be so lucky. Experts at NOAA predict there will be 17 to 25 named storms for the year. Out of those two dozen or so forecasted tempests, scientists think as many as 13 could become hurricanes, including 4 to 7 major hurricanes.

The confidence range for those estimates is 70 percent, and other institutions have settled on similar numbers.

"Perhaps we can thank El Niño somewhat for the lack of hurricane formation in the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico," theorizes Brian McNoldy, a tropical cyclone expert at the University of Miami.

"But that probably won't hold for this year."

Just recently on X, McNoldy pointed out that since 1935, only four Category 5 hurricanes (with winds over 252 kph) have made landfall in the US. All of them came from storms that were not declared hurricanes until just three days before they hit the coast.

Predicting which named storms will develop into intense hurricanes and make landfall is extremely tricky work, but it's crucial for saving lives and infrastructure.

Last year, for instance, the Category 5 hurricane that hit Acapulco, Mexico, downright defied the predictions of meteorologists, wreaking havoc.

Researchers at NOAA and several US universities are working hard to modify those models, so they can better predict such outcomes.

"It's sort of like finding why grandma's cookies taste so good," explains oceanographer Lynn "Nick" Shay from the University of Miami.

"We know what some of those ingredients are. But what are the correct ratios of the ingredients? No one really knows."

This hurricane season, scientists at NOAA are trialing two new hurricane forecast models. Let's hope those systems perform better than they did last year.