Cassini's glorious demise, in which it will plunge into the mysterious heart of Saturn, is now just two short weeks away.

And to commemorate the occasion, you can't just use any old symphony - which is why a team of astrophysicists has made music out of the orbital dance between Saturn and its moons.

It's a fitting send-off to the probe's 13 years collecting an incredible amount of data about one of our solar system's most beloved planets.

The music isn't made from the sound of Saturn's radio emissions (a spooky experience, if you've never heard it before). Instead, a team from the University of Toronto created the music based on the orbital rhythms of Saturn and its moons.

"To celebrate the Grand Finale of NASA's Cassini mission next month, we converted Saturn's moons and rings into two pieces of music," explained astrophysicist and musician Matt Russo in a press statement.

He joined forces with fellow astrophysicist Dan Tamayo of UT Scarborough and fellow musician Andrew Santaguida for the project.

What they based the music on is called orbital resonance. This is when things orbit at different speeds, but return to their original position in the same timeframe.

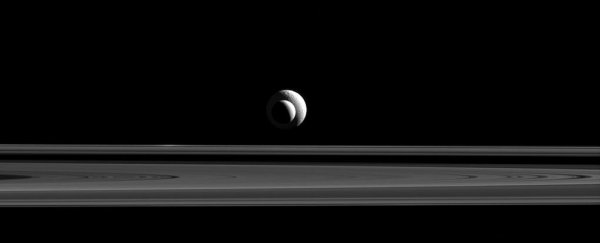

For instance, Saturn's first large moon (as opposed to the planet's small and shepherd moons), Mimas, completes two orbits for every one completed by third large moon Tethys.

This pattern can also be observed with the second and fourth large moons, Enceladus and Dione, too. Fifth and sixth large moons Rhea and Titan are then used to complete the first piece of music, the orbital frequencies of all six moons shifted up 27 octaves into human hearing range.

Using a simulation of the moon system developed by Tamayo, a note is played every time a moon completes an orbit.

"Since doubling the frequency of a note produces the same note an octave higher, the four inner moons produce only two different notes close to a perfect fifth apart," Russo said.

"The fifth moon Rhea completes a major chord that is disturbed by the ominous entrance of Saturn's largest moon, Titan."

The sound then flies over the rings, the pitches determined by their individual orbital frequencies, before a final chord, representing Cassini's descent, created by combining the oscillation frequencies of Saturn.

The second piece was based on the orbital resonance of Janus and Epimetheus, a pair of tiny moons unique in the solar system (as far as we know). They are what is known as co-orbital moons, sharing an irregular orbit very close to each other.

Because one is slightly closer to Saturn (by about 50 kilometres or 31 miles), it orbits slightly faster, so eventually it will catch up. When this happens, the gravitational interplay between the two planets catches the one behind and swings it out in front of the other.

They exchange places every four years, never drawing closer than around 15,000 kilometres (9,320 miles) from each other. The next exchange is due in 2018.

The team's composition simulates this orbit within the final few months of Cassini's mission, with Janus drawing slowly closer to Epithemeus. For each orbit, Russo plays a C-sharp note, with a longer cello note underneath representing the resonance.

"Each ring is like a circular string, being continuously bowed by Janus and Epimetheus as they chase each other around their shared orbit," Russo said.

The two pieces of music will be accompanied by a tactile wooden carving of Saturn's rings that people can follow along with the music at a fundraiser at the Canadian National Institute for the Blind's Night Steps on September 15.

You can also see the team's previous work, transcribing the TRAPPIST-1 system into music, on their website.