At this point, you're probably fully aware of how hot it is. But in case you're unaware: It's really, really hot.

In fact, 2016 is likely to be the hottest year on record, increasing 2.3 degrees Fahrenheit (1.3 degrees Celsius) above pre-industrial averages.

That brings us dangerously close to the 2.7-degree-Fahrenheit (1.5-degree-Celsius) limit set by international policymakers for global warming.

"There's no stopping global warming," Gavin Schmidt, a climate scientist who is the director of NASA's Goddard Institute of Space Studies, told Business Insider. "Everything that's happened so far is baked into the system."

That means that even if carbon emissions dropped to zero tomorrow, we'd still be watching human-driven climate change play out for centuries. And, as we all know, emissions aren't going to stop tomorrow. So the key thing now, Schmidt said, is slowing climate change down enough to make sure we can adapt to it as painlessly as possible.

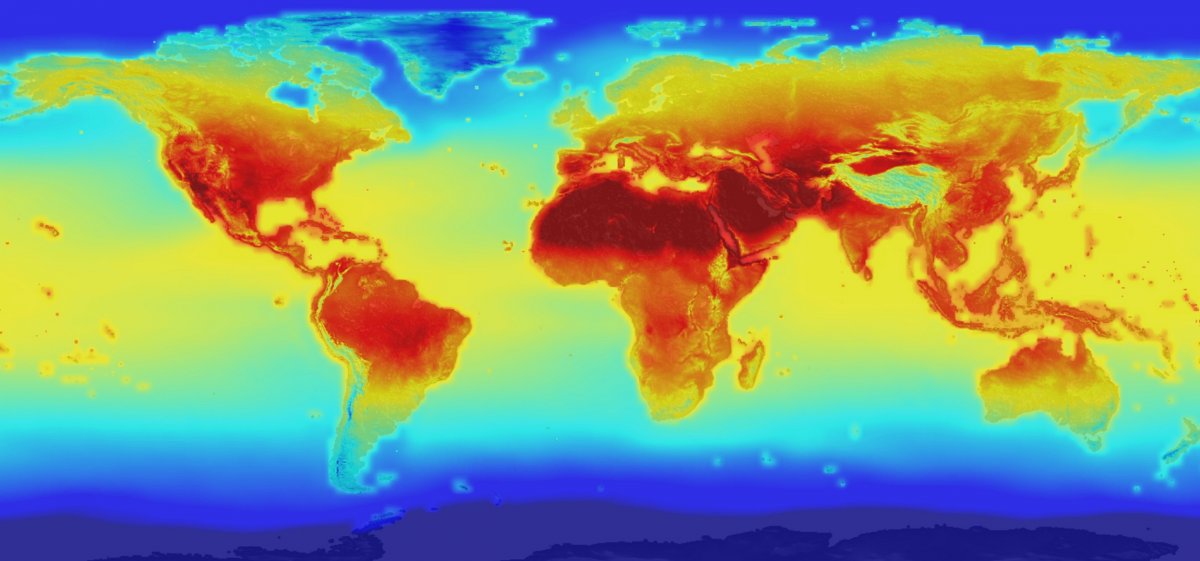

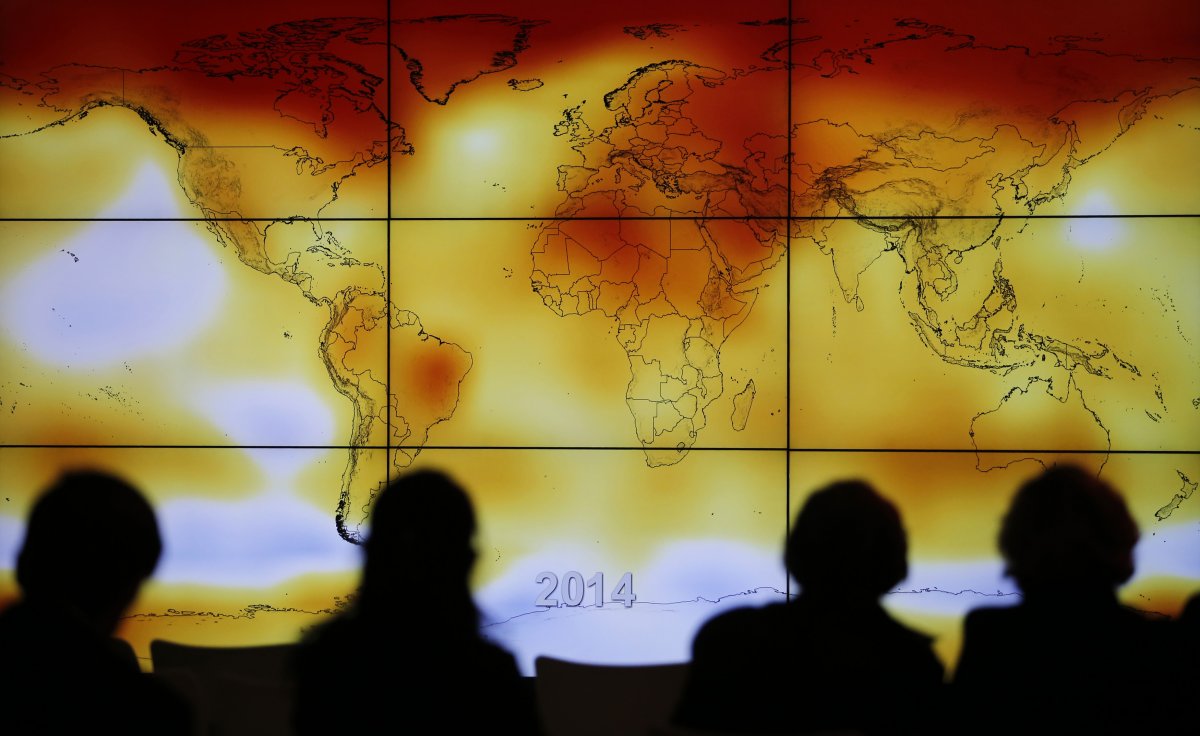

This is what Earth could look like within 100 years if we do, barring huge leaps in renewable energy or carbon-capture technology.

"I think the 1.5-degree [2.7-degree F] target is out of reach as a long-term goal," Schmidt said. He estimated that we will blow past that by about 2030.

Stephane Mahe/Reuters

Stephane Mahe/Reuters

But Schmidt is more optimistic about staying at or under 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit, or 2 degrees Celsius, above preindustrial levels – the level of temperature rise the UN hopes to avoid.

Let's assume we land between those two targets. At the end of this century, we're already looking at a world that is on average 3 degrees or so Fahrenheit above where we are now.

But average surface temperature alone doesn't fully capture climate change. Temperature anomalies – or how much the temperature of a given area is deviating from what would be 'normal' in that region – will swing wildly.

Oli Scarff/Getty

Oli Scarff/Getty

Source: Tech Insider

For example, the temperature in the Arctic Circle last winter soared above freezing for one day. It was still cold for Florida, but it was extraordinarily hot for the arctic. That's abnormal, and it will start happening a lot more.

Bob Strong/Retuers

Bob Strong/Retuers

Source: The Washington Post

That means years like this one, which had the lowest sea-ice extent on record, will become common. Summers in Greenland could become ice-free by 2050.

Source: Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems

Even 2015 was nothing compared with 2012, when 97 percent of the Greenland Ice Sheet's surface started to melt in the summer. It's typically a once-in-a-century occurrence, but we could see this kind of extreme surface melt every six years by end of the century.

Source: Climate Central, National Snow & Ice Data Centre

On the bright side, ice in Antarctica will remain relatively stable, making minimal contributions to sea-level rise.

Andreas Kambanis/Flickr

Andreas Kambanis/Flickr

Source: Nature

But in our best-case scenarios, oceans are on track to rise 2 to 3 feet (0.6 to 0.9 metres) by 2100. Even a sea-level rise below 3 feet (0.9 metres) could displace up to 4 million people.

Thomas Reuters

Thomas Reuters

Oceans not only will have less ice at the poles, but they will also continue to acidify in the tropics. Oceans absorb about a third of all carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, causing them to warm and become more acidic.

Brandi Mueller for Argunners Magazine

Brandi Mueller for Argunners Magazine

Source: International Geosphere-Biosphere Program

If climate change continues unabated, nearly all coral reef habitats could be devastated. Under our best-case scenario, half of all tropical coral reefs are still threatened.

Source: International Geosphere-Biosphere Program

But the oceans aren't the only place heating up. Even if we curb emissions, summers in the tropics could increase their extreme-heat days by half after 2050. Farther north, 10 percent to 20 percent of the days in a year will be hotter.

Source: Environmental Research Letters

But compare that with the business-as-usual scenario, in which the tropics will stay at unusually hot temperatures all summer long. In the temperate zones, 30 percent or more of the days will be what is now unusual.

Matt York/AP Photo

Matt York/AP Photo

Source: Environmental Research Letters

Even a little bit of warming will strain water resources. In a 2013 paper, scientists used models to estimate that the world could see more severe droughts more frequently – about a 10 percent increase. If unchecked, climate change could cause severe drought across 40 percent of all land, double what it is today.

Reuters

Reuters

Source: PNAS

And then there's the weather. If the extreme El Niño event of 2015 to 2016 was any indication, we're in for much more dramatic natural disasters. More extreme storm surges, wildfires, and heat waves are on the menu for 2070 and beyond.

Reuters/Max Whittaker

Reuters/Max Whittaker

Source: Environment360

Right now, humanity is standing on a precipice. We can ignore the warning signs and pollute ourselves into what Schmidt envisions as a "vastly different planet" – roughly as different as our current climate is from the most recent ice age.

Reuters

Reuters

Or we can innovate solutions. Many of the scenarios laid out here assume we're reaching negative emissions by 2100 – that is, absorbing more than we're emitting through carbon-capture technology.

Reuters/Aly Song

Reuters/Aly Song

Source: The Guardian

Schmidt says we are likely to reach 2100 with a planet somewhere between "a little bit warmer than today and a lot warmer than today".

Heinz-Peter Bader/Reuters

Heinz-Peter Bader/Reuters

But the difference between 'a little' and 'a lot' on the scale of Earth is one of millions of lives saved, or not.

This article was originally published by Business Insider.

More from Business Insider: