Eight thousand light-years from Earth, just below Scorpio, there's a cosmic serpent that's been hiding a secret sting in its tail. In a sinuous curl of glowing dust, astronomers have discovered a binary star system unlike any other in the Milky Way.

It's a pair of rare, old, and unstable stars right on the brink of one of the most violent events in the Universe - stellar supernova. And when that happens, the team has determined, there's a good chance it will produce something even more unusual - a gamma-ray burst.

These are some of the most energetic events ever recorded - an explosive burst of gamma rays releases more energy in 10 seconds than the Sun could in 10 billion years. Except never before has a gamma-ray burst been caught originating in the Milky Way.

The star system that could be the first has been named Apep, after the Ancient Egyptian serpent-god of chaos.

"This is the first such system to be discovered in our own galaxy," said astronomer Joseph Callingham of the Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy (ASTRON). "We never expected to find such a system in our own backyard."

It's almost difficult to convey just how weird Apep truly is. The two stars in the binary system are known as Wolf-Rayet stars. These are very hot, very luminous, very old stars that typically have at least 25 times the mass of the Sun.

And this particular pair is losing that mass at a tremendous rate, hurtling towards a violent end.

Because this stage of a supermassive star's life doesn't last very long, Wolf-Rayet stars are pretty rare - we only know of a couple of hundred in the Milky Way, of the estimated at least 100 billion or so stars total (although it's possible more are concealed by gas and dust).

That's why a binary system consisting of two Wolf-Rayet stars is an incredible find - although possibly not uncommon out there in the Universe, since up to 85 percent of all stars may be in a binary pair.

"Most massive stars - including Wolf-Rayets - are probably born in multiple systems. When you get to the top end of the stellar kingdom, doubles and even triples and quads become increasingly common," explained astrophysicist Peter Tuthill of the University of Sydney to ScienceAlert.

"However, Wolf-Rayet stars are so bright, it can be hard to even know if there are companions."

Since they're so bright, how did the light of not one, but two Wolf-Rayet stars so close to home evade detection for so long?

According to Callingham, who found it while performing the mundane task of comparing archival datasets from X-ray and radio surveys, it was in a particularly tricky region of the sky, so the observation just "fell through the cracks".

"In all honesty, it probably should have been found before us, particularly by infrared astronomers that specialise in finding systems like this," he said.

However, the area where the pair is located is so crowded with bright stars, infrared surveys since the 1980s had ended up placing it in the "too hard basket".

But when Callingham showed his initial finding to Tuthill, the latter became intrigued by the extreme infrared properties of the object. As an imaging specialist, he suggested a high-resolution infrared observation to get a close look at the dust using the ESO's Very Large Telescope.

That's when it became "clear we had found something really special," Tuthill said.

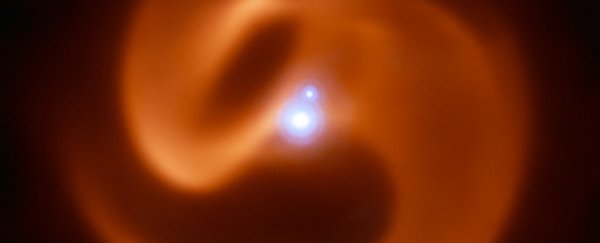

That something was a sinuous plume being carved out of the dust and gas around the binary pair. It's a rare type of nebula called a pinwheel nebula, found in multiple star systems in which at least one of the stars is a Wolf-Rayet.

(University of Sydney)

(University of Sydney)

The nebula is born from the incredibly powerful stellar winds blown by the two stars. Where the two winds collide, a plume of dust spirals outwards, much like a lawn sprinkler.

Just to make the find even more wonderful, in the case of Apep, there's another peculiarity: the gas in the nebula is moving at a tremendously high speed, around 3,400 kilometres per second.

But the dust is only moving at a fraction of that speed: 570 km/s. That can happen when a star is rotating incredibly fast, almost tearing itself apart, generating high-speed winds at its poles, but much slower ones around its equator.

One of Apep's Wolf-Rayet stars is rotating at this extreme rate, which means that, when it runs out of fuel, it's going to seriously blow. The poles will collapse before the equator, which researchers think will produce an incredible gamma-ray burst.

"This is the part that was unexpected, and nobody had been able to show before," Tuthill said. "In fact, astronomers are divided over whether any Wolf-Rayets in this state should exist in the galaxy at all."

Of course, it's important to bear in mind that "just about to explode" means something different in cosmic terms versus human terms. It could happen at any time in the… next few hundred thousand years.

In the meantime however, astronomers won't be sitting around twiddling their thumbs. Apep represents a terrific opportunity.

"This star is such a spectacularly powerful and luminous object that it nearly belongs in a category by itself," Tuthill said.

"And fortunately for us, it is encoding a lot of the physics that we would otherwise not be able to see by waving a huge flag - the spiral tail - that we can study. It is an example where beauty and truth, as Keats would have it, converge."

The team's research has been published in the journal Nature.