It's an accomplishment that scientists have dreamed about for more than half a century. At last, a massive international team of researchers has mapped in exquisite detail every neuron in the brain of an adult animal with eyes and legs.

The nifty noggin, which anyone can now freely peruse, is no larger than a poppy seed, and yet it contains 139,255 neurons and 50 million connections.

It belongs to an adult female fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster).

This might seem like a small victory compared to a human brain, which contains 80 billion neurons and 100 trillion connections, but it's a huge leap from where neuroscientists started in the 1960s.

If history is anything to go by, the research could be in the running for a future Nobel prize.

"This is a major achievement," says neuroscientist Mala Murthy from Princeton University, who helped lead the team.

"There is no other full brain connectome for an adult animal of this complexity."

The only other map that comes close is a 3D diagram of the adult fly 'hemibrain', but it includes only around 20,000 neurons.

Emory University biologist Anita Devineni, who was not involved in the current research, predicts this new map will "transform Drosophila neuroscience" in an accompanying commentary in Nature.

Scientists first started mapping the wiring of animal brains roughly half a century ago, and these initial attempts were focused on a very simple creature: the sightless and legless worm, Caenorhabditis elegans.

In 2002, the scientists behind this partial brain map of just 302 neurons shared a Nobel Prize.

Today, the same feat, which once took over 12 years to complete, takes less than a month.

In 2023, researchers completed a much larger brain map, including all 3,016 neurons in the larva of a fruit fly.

Once again, however, this animal could not walk or see.

An adult fruit fly is the next big step. Its brain networks, which underlie sight and the complicated movements of walking, are similar to those in humans, and they can now be explored in greater detail than ever before.

"Flies can do all kinds of complicated things like walk, fly, navigate, and the males sing to the females," explains molecular biologist Gregory Jefferis from the University of Cambridge, who helped lead the research.

"Brain wiring diagrams are a first step towards understanding everything we're interested in – how we control our movement, answer the telephone, or recognize a friend."

The team that put this diagram together included researchers from 122 institutions, with major contributions from Princeton University, the University of Cambridge, and the University of Vermont.

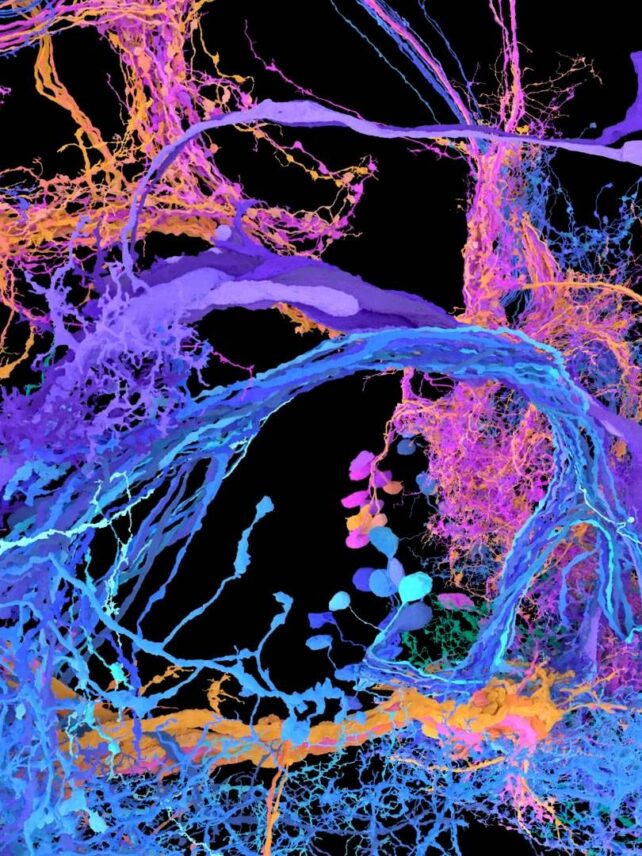

The map required more than 7,000 slices of a female fruit fly brain and 21 million images, which could have filled 100 typical laptops with their data.

An artificial intelligence program, built at Princeton University, was essential in combing through the data.

The results are now compiled in no less than 9 related papers, with overlapping groups of authors.

One paper annotates the entire map. To correct for computer errors, a crowdsourcing project was built where researchers and volunteers globally could proofread the names and functions given to neurons. It would have taken one person 33 years working full time to make all 3 million or so manual edits.

Of all 8,453 known and named cell types in the diagram, covering 96 percent of all neurons, more than 4,500 are new to science.

"Just like you wouldn't want to drive to a new place without Google Maps, you don't want to explore the brain without a map," explains neuroscientist Sven Dorkenwald, a 2023 graduate of Princeton.

"What we have done is build an atlas of the brain, and added annotations for all the businesses, the buildings, the street names. With this, researchers are now equipped to thoughtfully navigate the brain, as we try to understand it."

In one accompanying paper, for instance, scientists used the annotated map to trigger neurons in a fruit fly's computer brain, causing it to extend its proboscis for sugar, just like occurs in real flies when those neurons are activated.

Today, 6 different Nobel Prizes have been given to researchers studying the common fruit fly. A 7th could be on the way.

The main findings are published in Nature.