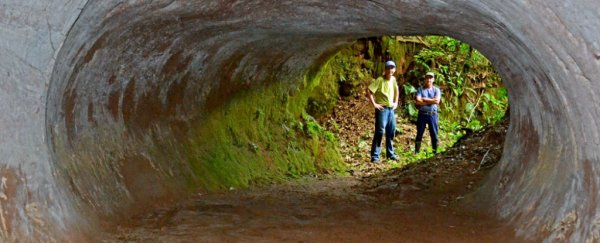

Researchers have found several colossal burrows in South America that are so huge and neatly constructed, you'd be forgiven for thinking humans dug them as a passageway through the forest.

Turns out, they're far more ancient than they look, estimated to be at least 8,000 to 10,000 years old, and no known geologic process can explain them. But then there's the massive claw marks that line the walls and ceilings - it's now thought that an extinct species of giant ground sloth is behind at least some of these so-called palaeoburrows.

"I didn't know there was such a thing as palaeoburrows," lead researcher behind the latest study, Heinrich Frank from the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil, told Andrew Jenner at Discover.

"I'm a geologist, a professor, and I'd never even heard of them."

Researchers have known about these tunnels since at least the 1930s, but back then, they were considered to be some kind of archaeological structure - remains of caves carved out by our ancient ancestors, perhaps.

Fast-forward to 2010, when geologist Amilcar Adamy from the Brazilian Geological Survey decided to investigate rumours of a peculiar cave in the state of Rondonia, to the north-west of the country.

Amilcar Adamy

Amilcar Adamy

The structure was huge, and according to Jenner, it's still the largest known palaeoburrow in the Amazon, and is twice the size of the second largest palaeburrow in Brazil.

Adamy had gone to investigate the tunnel, determined to attribute it to some kind of geologic process, but once he saw it with his own eyes, he couldn't think of any natural process that would create such a deliberate-looking structure.

"I'd never seen anything like it before," Adamy told Jenner. "It really grabbed my attention. It didn't look natural."

A few years later, Frank found his own strange cave, thousands of kilometres away in the town of Novo Hamburgo. Once he knew what to look for, he found hundreds of them scattered across the Brazilian landscape.

There are now more than 1,500 known palaeoburrows that have been found in southern and southeastern Brazil alone, and there appear to be two different types: the smaller ones, that reach up to 1.5 metres in diameter; and the bigger ones, that can stretch up to 2 metres in height and 4 metres in width.

It wasn't until Frank started climbing inside them that he realised the extent of these tunnels, which can extend for up to 100 metres, and occasionally branch off into separate chambers.

When he looked up at the ceiling, he got his first big clue about what could be behind their construction - distinctive grooves in the weathered granite, basalt, and sandstone surfaces, which he's identified as the claw marks of a massive, ancient creature.

"Most consist of long, shallow grooves parallel to each other, grouped and apparently produced by two or three claws," Frank and his team explained in a 2016 paper.

"These grooves are mostly smooth, but some irregular ones may have been produced by broken claws."

Heinrich Frank

Heinrich Frank

The discovery seemed to answer one of the long-standing questions in palaeontology regarding the ancient megafauna that roamed the planet during the Pleistocene epoch, from about 2.5 million years ago to 11,700 years ago: Where were all the burrows?

As Frank and his colleagues explain, it's estimated that about half of the mammalian species on Earth right now are classified as semi-fossorial - meaning they spend some time inside burrows, but have to go outside to feed.

Around 3.5 percent of living species are completely fossorial, which means they spend all their lives underground.

Considering all the world's species have evolved from more ancient versions of themselves, it stands to reason that similar proportions of fossorial and semi-fossorial species would have existed around the time of the Pleistocene megafauna.

But despite the abundance of fossilised remains proving the existence of these creatures, for centuries, researchers could not identify any evidence of burrows - something that was likely a combination of burrows collapsing over thousands of years, and researchers not knowing what to look for.

Based on the size of the structures and the claw marks left in their walls, researchers are now confident that they've found the megafauna burrows, and have narrowed down the owners to giant ground sloths and giant armadillos.

"There's no geological process in the world that produces long tunnels with a circular or elliptical cross-section, which branch and rise and fall, with claw marks on the walls," Frank told Discover.

"I've [also] seen dozens of caves that have inorganic origins, and in these cases, it's very clear that digging animals had no role in their creation."

Below is a summary of how the various tunnel diameters match up to known species of ancient armadillos and sloths:

Renato Pereira Lopes et. al.

Renato Pereira Lopes et. al.

The researchers suspect that the biggest palaeoburrows were dug by humungous South American ground sloths from the extinct Lestodon genus.

But despite these creatures stretching up to 4.6 metres (15 feet) and weighing roughly 2,590 kg (5,709 pounds), a single ground sloth would have spent much of its lifespan dedicated entirely to constructing tunnels as large and extensive as the palaeoburrows are.

And why bother? Frank and his team aren't sure if the extensive caverns were used to escape the climate, predators, or humidity, but told Jenner at Discover that all of these explanations seem unlikely, as a much smaller burrow would have suited those purposes just fine.

It could be that several individuals inherited the burrows over generations, and kept adding to the structure to make it enormous, but that's something the researchers will need to confirm with further observations.

With so many questions left to answer, let's just appreciate the fact that the sheer scale of things so 10,000 years ago was ridiculous, and we really just want a time machine so we can curl up with a giant sloth in its Narnia-esque mansion.

The paper has been published in Ichnos.