A new study shows that undertaking a memory consolidation exercise during sleep in combination with a structured treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) during the day may help reduce the severity of PTSD symptoms.

The team behind the study, from the Amsterdam University Medical Center and University of Amsterdam in the Netherlands, says that the application of the sleep technique – known as targeted memory activation (TMR) – could eventually act as a helpful booster on top of regular treatments for PTSD.

"Our goal is to unlock sleep as a new treatment window for PTSD," says Hein van Marle, a psychiatrist and neuroscientist from the Amsterdam University Medical Center. "This is the first proof of concept for potentially enhancing daytime treatment effects during sleep."

An emerging yet relatively controversial treatment for PTSD called eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) involves patients recalling traumatic experiences while being distracted by a moving light or clicking sounds.

The process aims to reprogram the way the memories are stored in the brain to make them less distressing. Exactly how this might occur isn't clear, though reviews have found the treatment to be more or less as effective as cognitive behavioural therapy. EMDR seems to work well for some, yet the fact a lot of patients don't respond to it coupled with a high emotional demand sees many patients drop out of the treatment.

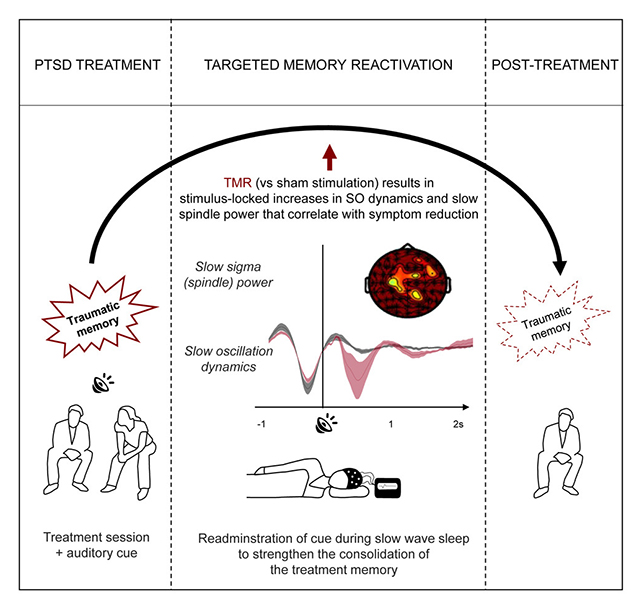

In this study, 33 people with PTSD were put through an evening EMDR session before being monitored during their sleep. For 17 of the individuals, the same clicking sound used during the EMDR session was played while they slept.

Scans showed that levels of brain wave activity linked to memory processing and consolidation were higher in these people compared to the others, suggesting the TMR was reinforcing the benefits of the EMDR session.

"During the night of TMR stimulation, we saw that presenting the EMDR clicks effectively enhanced the sleep physiology responsible for memory consolidation, with more enhancement leading to more significant reductions in symptoms," says van Marle.

The most significant improvement was seen avoidance behavior: the tendency for someone to avoid triggers related to their traumatic event. Those who received TMR stimulation were less likely to avoid stimuli associated with their traumatic memory when listening to an audio retelling, compared with those who had EMDR but no TMR.

However, it's important to note that when all PTSD symptoms were taken into account, no significant difference in clinical outcomes was detected between those who received TMR therapy and those who didn't.

The researchers argue that could be due in part to EMDR being "quite effective" on its own.

What the study does show is that TMR doesn't trigger any bad mental experiences or nightmares, and the brain activity and avoidance behavior results point to a positive impact – which can be explored in studies covering more people and across a longer period in the future.

"The sleep and memory field has been wary to apply TMR in PTSD patients," says van Marle. "We are really happy to see that TMR has no negative effects on these patients."

The research has been published in Current Biology.