They say what goes around comes around, but it's unlikely the saying was supposed to ever refer to meteorites.

And yet here we are. Scientists are seeking to confirm that a black rock discovered in Morocco in 2018 departed Earth's pull for outer space, only to return to it like a prodigal child.

If true, this rock – officially called 'Northwest Africa (NWA) 13188' – would be the first meteorite (that we know about) to have made this extraordinary round trip.

That this 646-gram 'boomerang space rock' might've made a celestial excursion isn't the only strange thing about it.

NWA 13188's bubbly appearance, texture of crystals, and precise chemical makeup hint strongly at the kind of rocks that form out of the molten minerals produced by volcanoes near sinking oceanic plates right here on Earth.

Throw in its mix of oxygen isotopes and signature of trace elements, and it becomes highly doubtful that this rock is a meteorite. At least, not your typical space-rock variety.

Yet according to Jérôme Gattacceca, a geophysicist from French National Centre for Scientific Research who presented his team's findings at the Goldschmidt geochemistry conference in France, the rock has had an interesting journey that has seen it spend a significant amount of time in orbit.

Its concentrations of Helium-3, Beryllium-10, and Neon-21 could only be explained by exposure to cosmic rays – radiation found in outer space but largely blocked by Earth's magnetic field.

While the concentration of these isotopes was lower than other meteorites, it was significantly higher than other rocks from Earth.

This suggested that NWA 13188 had been exposed to galactic cosmic rays for a short but significant period, as many as a few tens of thousands of years.

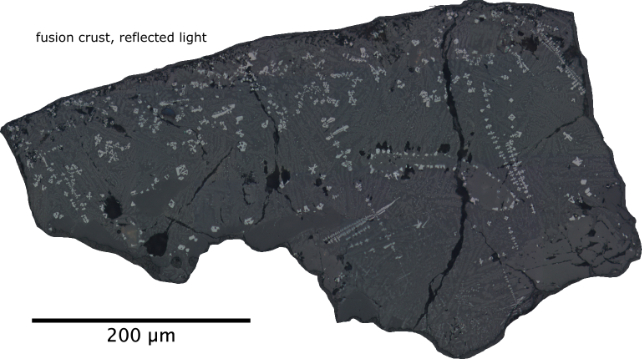

NWA 13188 also had a glassy 'fusion crust', suggesting it may have melted as it made a fiery entry into the Earth's atmosphere.

All this "preclude that NWA 13188 is a man-made 'fake' meteorite", Gattacceca and his colleagues write.

"Therefore, we consider NWA 13188 to be a meteorite, launched from the Earth and later re-accreted to its surface," they conclude.

How this Earth rock made it into space is a mystery, but it's possible it was ejected during a volcanic eruption or thrown into space when another meteorite smashed into Earth, the researchers say.

To go into orbit, a rock shot from the mouth of a raging volcano would need to be moving at tens of thousands of kilometers per hour – magnitudes faster than most rocks are estimated to fly.

The highest volcano plumes usually only reach around 31-45 kilometers above the Earth (101,700-147,600 feet), so it's unlikely that volcanoes could launch rocks into space.

Some collisions between Earth and large asteroids would have been strong enough to fire rocks into the Solar System.

A 4-billion-year-old Earth rock – the earliest known to science – was found on the Moon during the Apollo 14 mission in 1971. This rock was probably flung from Earth to the then much-closer Moon after an asteroid collision.

The age of NWA 13188 is unknown, but Gattacceca's team is working on dating the rock by measuring the concentrations of an isotope of argon.

The unpublished research hasn't persuaded everyone. "When you're claiming extraordinary hypotheses, you need extraordinary evidence to back it up. I am still unconvinced," planetary scientist Philippe Claeys told Alex Wilkins at New Scientist.

Meteorites from Mars have also been found in the Sahara desert; a 4.4-billion-year-old rock called 'Black Beauty' was discovered by local meteorite hunters and sold to a private collection in 2011. It now has a market value of more than US$10,000 per gram.

The Sahara Desert is an ideal place to search for meteorites as the black stones pop against the sand, and there is little vegetation to obscure the view.

As many as 780,000 meteorites could be lurking somewhere in the Sahara, making it the best meteorite-hunting location outside of Antarctica.