Australian researchers have developed a tiny 'bionic spine' that can be implanted into a blood vessel next to the brain to read electrical signals and feed them into an exoskeleton, bionic limbs, or wheelchair to give paraplegic patients greater mobility based on subconscious thoughts.

"Our vision, through this device, is to return function and mobility to patients with complete paralysis by recording brain activity and converting the acquired signals into electrical commands, which in turn would lead to movement of the limbs through a mobility assist device like an exoskeleton. In essence this a bionic spinal cord," said neurologist and lead researcher, Thomas Oxley from the Royal Melbourne Hospital and the University of Melbourne.

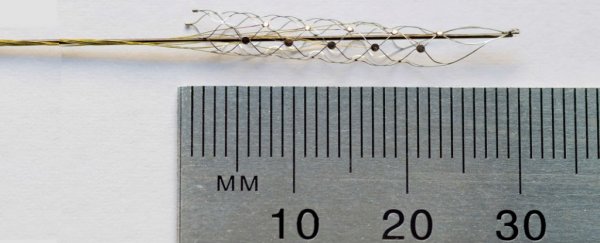

One of the biggest advantages of the new device is how easy it is to implant. Measuring 3 cm long and a few millimetres wide - basically the size of a paperclip - it requires a small cut to be made in the back of a patient's neck, and is fed into the blood vessels that connect to the brain via a catheter.

Once it hits the top of the motor cortex - where the nerve impulses that control voluntary muscular activity originate - the bionic spine is left behind as the catheter is removed. The whole procedure should only take a few hours, the team reports.

"We have been able to create the world's only minimally invasive device that is implanted into a blood vessel in the brain via a simple day procedure, avoiding the need for high risk open brain surgery," said Oxley.

"This is a procedure that Royal Melbourne staff do commonly to remove blood clots," one of the team, Nicholas Opie from the University of Melbourne, told Melissa Davey at The Guardian. "The difference with our device is we have to put it in, and leave it in."

Once the bionic spine is implanted, the tiny electrodes on its exterior will stick to the walls of a vein and start recording electrical signals from the motor cortex. These signals are then transmitted to another device implanted in the patient's shoulder, which translates them into commands to control wheelchairs, exoskeletons, prosthetic limbs, or computers via bluetooth.

This isn't something a patient will immediately know how to do, but the researchers say that with training, deliberate thoughts about manoeuvring bionic limbs and other apparatuses will eventually be controlled by their subconscious.

While this is certainly not the first piece of technology designed to give paralysed patients the ability to move again using neural signals, the team behind it says it's an improvement on previous devices because of how tiny it is.

"[M]ost require invasive surgery involving removing a piece of the skull, known as a craniotomy, and which carries a risk of infection and other complications," Davey explains for The Guardian, adding that a few recently unveiled devices involve bulky electrode caps and robotic suits.

"[A]nother existing procedure, which involves puncturing thousands of electrodes into the brain, is only effective for up to a year before the brain starts treating it as a foreign object and grows scar tissue over it," she describes.

The device has so far only been tested in sheep, but the team plans to start human trials in 2017, with three patients to be selected from Royal Melbourne Hospital's Austin Health spinal cord unit as the first recipients.

The technology has been described in Nature Biotechnology.