Researchers have verified the authenticity of an ancient Maya text from the 13th century, solving the long-standing riddle of whether the mysterious fragment was actually genuine.

The Grolier Codex, thought to have been uncovered by looters in the 1960s, has long been treated with suspicion by archaeologists and historians, but a new analysis of the text suggests that it is both genuine and the oldest known manuscript written in the Americas.

Whereas the other surviving Maya codices were found during the 19th century, the Grolier long stood out as a potential fake, only coming to light in the late 20th century. The pages were reportedly found by looters in a cave in Chiapas, Mexico, before findings its way into a private collection.

"Its history is cloaked in great drama," says anthropologist Stephen Houston from Brown University. "It was found in a cave in Mexico, and a wealthy Mexican collector, Josué Sáenz, had sent it abroad before its eventual return to the Mexican authorities."

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

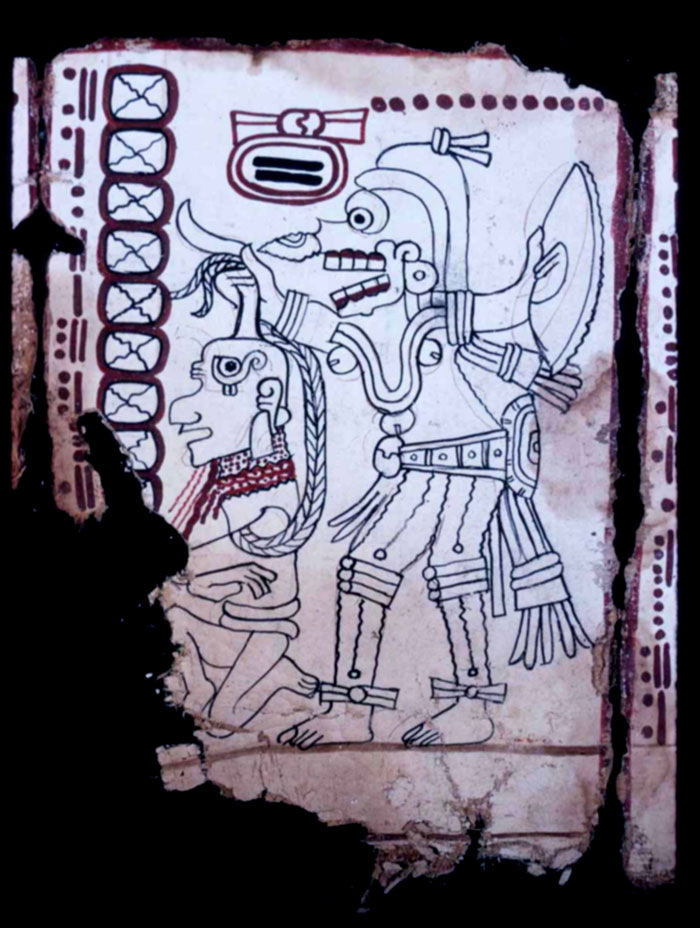

The codex takes its name from the Grolier Club in New York City, where it was displayed in the 1970s, but ever since its discovery, researchers have debated whether or not the pages were a forgery, cunningly designed to emulate the style of ancient Maya writing, illustrations, and materials.

The fact that it was discovered by looters and not archaeologists also didn't help.

And then there's Sáenz's colourful telling of how he came into possession of the manuscript, which has long encouraged doubters.

The collector claimed he was contacted by two looters about the cave discovery, who transported him in an aeroplane - where the compass was concealed by a cloth, no less – to a remote airstrip. Basically, it's Indiana Jones, starring a wealthy Mexican antiquities nut.

Other items found in the cave alongside the Grolier Codex included a small wooden mask and a sacrificial knife. But while these items were long ago recognised as authentic, the Grolier itself remained disputed in academic circles.

"It became a kind of dogma that this was a fake," says Houston. "We decided to return and look at it very carefully, to check criticisms one at a time. Now we are issuing a definitive facsimile of the book. There can't be the slightest doubt that the Grolier is genuine."

Houston and his team reviewed all known research on the codex, "without regard to the politics, academic and otherwise, that have enveloped the *Grolier*", they explain in their paper.

The researchers analysed the origins of the manuscript, examined its use of illustrations and iconography, and compared its craftsmanship to the known stylings of Maya painters.

The team also carbon-dated the pages, which revealed that the Grolier actually pre-dates the more established Maya codices: the Dresden, Madrid, and Paris codices, named after the cities where they are kept.

The carbon dating puts the manuscript as originating in the 13th century, and the analysis of the text suggests a forgery in the 1960s would have been almost impossible, requiring knowledge of aspects of Maya culture that were not discovered by historians and scientists until later on in the 20th century.

While we'll have to wait and see what other researchers now make of the latest claims, it's exciting to think that we might have just traced the lineage of the oldest known pages written in the Americas. For their part, the study authors no longer shoulder any doubts.

"A reasoned weighing of evidence leaves only one possible conclusion: four intact Mayan codices survive from the Pre-Columbian period, and one of them," the researchers write, "is the *Grolier*".

The findings are reported in Maya Archaeology 3: Featuring the Grolier Codex.