Scientists have come across a new species of bacteria they're calling 'golden death' – microorganisms that can devour their parasitic roundworm hosts in hours by eating them from the inside out.

Rather a gory way to go if you're a parasitic worm, but these Chryseobacterium nematophagum bacteria could prove very useful in helping control the spread of such worms (or nematodes) in plants, animal livestock, and even human beings.

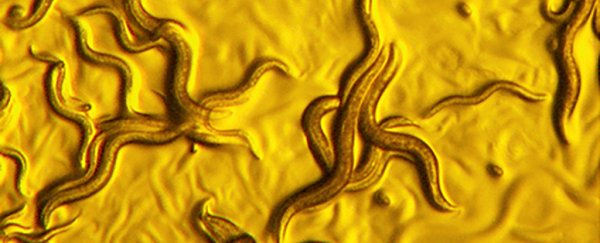

Translated literally, Chryseobacterium nematophagum means "golden bacteria, nematode-eating", a name chosen because of the golden hue that can be seen while the microorganisms are feasting.

Before roundworms attack their final host – an animal or a human – they first feed on bacteria as they develop. Usually those bacteria are disabled before they reach the parasite's stomach, making them harmless.

But C. nematophagum not only survives, it fights back.

"This study describes a newly discovered bacterial species, called Chryseobacterium nematophagum – or golden death bacillus – that effectively kills a wide range of important nematode parasites," says one of the researchers, parasitologist Antony Page from the University of Glasgow in the UK.

The 'golden death' bacterium was found by extracting bacteria from free-living roundworms collected in rotting fruit in France and India, and then feeding it to nematode worm larvae of the Caenorhabditis elegans species (often used to study parasitic roundworms).

The C. elegans larvae fed with C. nematophagum bacteria were immobilised within an hour, with half the larvae killed within three to four hours. All the worms had been killed off by the time seven hours had passed, and after 24 hours only the exoskeletons of the worms were left.

A few days later, the exoskeletons were gone too. Ew.

C. nematophagum starts its attack in the mouth, dissolving the worm's internal defences that normally stop bacteria reaching the gut.

It looks like the worm larvae didn't see the threat coming either – C. elegans worms are normally experts at avoiding danger, but they happily stayed on the 'bacterial lawns' cultivated in the lab, feeding on the C. nematophagum bacteria until they got consumed from the inside out.

The researchers went on to take a closer look at which genes might be responsible for the bacteria's eager appetite, comparing genomes with five other Chryseobacterium species that don't devour nematodes.

They found genes responsible for enzymes able to break down the structural proteins and the tough exoskeletons (the cuticles) of a worm's body.

Finally, the team tested the C. nematophagum against 13 other types of parasitic worms, species more likely to cause problems for animals. The 'golden death' bacteria was effective against all but one of them.

With nematodes becoming more resistant to the drugs used to keep them at bay in pets and livestock, this new chomping bacteria could prove very useful. It might also one day be used in human treatments for roundworm, but that's a long way off yet.

"Our findings raise the possibility that C. nematophagum – or the specific properties that make it highly virulent in many nematode species – could provide a future means of controlling increasingly problematic parasites that currently are a major burden to public health and the farming industry," says Page.

The research has been published in BioMed Central.