"We know more about the Moon than the deep sea."

This idea has been repeated for decades by scientists and science communicators, including Sir David Attenborough in the 2001 documentary series The Blue Planet.

More recently, in Blue Planet II (2017) and other sources, the Moon is replaced with Mars.

As deep-sea scientists, we investigated this supposed "fact" and found it has no scientific basis. It is not true in any quantifiable way.

So where does this curious idea come from?

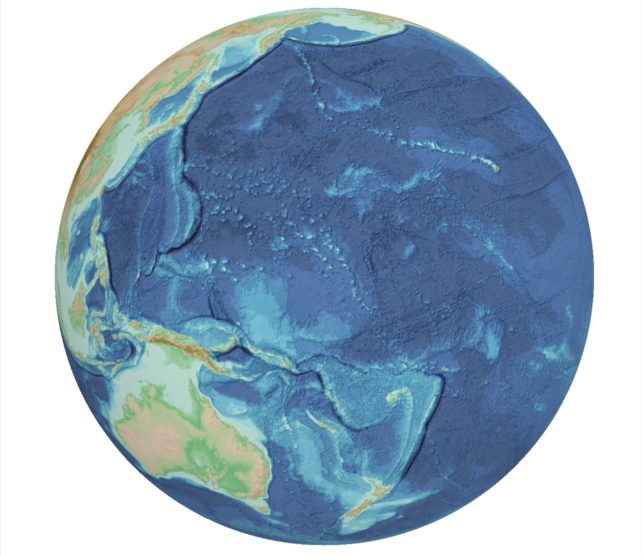

Mapping the deep

The earliest written record is in a 1954 article in the Journal of Navigation, in which oceanographer and chemist George Deacon refers to a claim by geophysicist Edward Bullard.

A 1957 paper published in the Journal of the Royal Society of Arts states: "the deep oceans cover over two-thirds of the surface of the world, and yet more is known about the shape of the surface of the moon than is known about that of the bottom of the ocean".

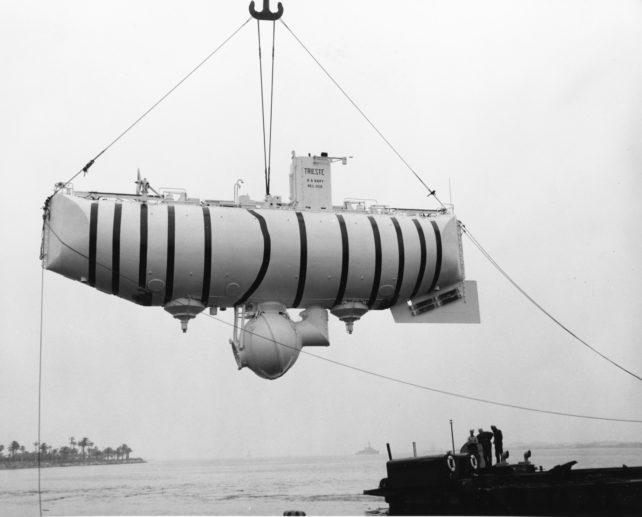

This refers specifically to the scant amount of data available on the topography of the sea floor and predates both the first crewed descent to the deepest part of the ocean, the Mariana Trench (1960), and the first Moon landing (1969).

This quote also predates the practice of using ship-mounted echo-sounders to map the sea floor from acoustic data, known as swath bathymetry.

Almost a quarter of the world's sea floor (23.4 percent, to be precise) has been mapped to a high resolution. This amounts to about 120 million square kilometers, or about three times the Moon's total surface area. This may be why the comparison has shifted to Mars, which has a surface area of 145 million square kilometers.

A surprising number of visitors

Another related and incorrect comparison is that more people have set foot on the Moon than have visited the deepest place on Earth.

This statement is difficult to substantiate. "The deepest place on Earth" could refer to the Mariana Trench, or just the deepest part of it (the Challenger Deep, named for the British survey ship HMS Challenger).

Nevertheless, at least 27 and as many as 40 or more people have visited the Challenger Deep as of early 2023. On the other hand, only 12 people have "set foot" on the Moon and 24 people have visited it.

Out of sight, out of mind

So why do people keep saying we know more about the Moon or Mars than the deep sea?

It feels natural to compare the deep sea to space. Both are dark, scary and far away.

But we can see the Moon very easily by simply looking up. By being able to see it, we accept an apparently glowing rock hanging in the sky more easily than that parts of the ocean are very deep. We can see the Moon wax and wane and we can experience the push and pull of the tides.

It feels like we know more about the Moon than the deep sea, because we are forced to accept its presence. It intrudes on our lives in a tangible way that the deep sea does not.

We don't think much about the deep sea unless we're watching a documentary or horror film, or perhaps reading about some "horrific alien-like monster" dredged up by a deep-sea trawler.

A useful analogy

Because the deep sea is so physically inaccessible, comparing it to space may offer a useful analogy for an otherwise difficult-to-imagine ecosystem. But some deep-sea scientists argue that the persistent estrangement of the deep sea minimizes the vast amount of research about it that has emerged in recent decades.

Deep-sea biology is relentlessly referred to as a discipline that knows less about its own field of study than a relatively small, barren rock devoid of atmosphere, water and life. And yet this self-deprecating line is repeated by scientists themselves, who may find that highlighting the deficit of knowledge about the deep sea helps to promote the need for ocean research.

Ultimately, the idea we know more about the Moon than the deep sea is at best about 70 years out of date. We know much more about the deep sea – but there is even more left to be known.![]()

Prema Arasu, Postdoctoral research fellow, The University of Western Australia; Alan Jamieson, Senior Lecturer in Marine Ecology, Newcastle University, and Thomas Linley, Research Associate, Marine Ecology, Newcastle University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.