When the 25-year-old woman arrived at the emergency room, she was weak, dizzy and experiencing shortness of breath. But her doctors immediately zeroed in on a much more concerning symptom.

"She looked physically blue," Otis Warren, an emergency medicine physician who treated the woman last year in Rhode Island, told The Washington Post.

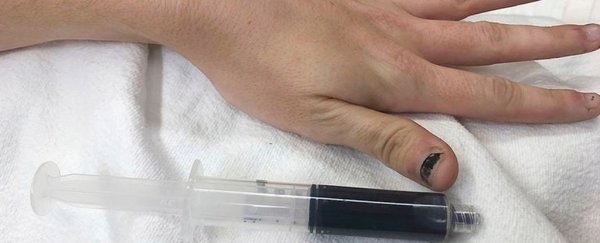

The woman's skin and nails had taken on a bluish tint - a common sign that the body isn't getting enough oxygen - and her blood had also turned unusually dark, according to a report published in Thursday's issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

Luckily, doctors knew exactly what was wrong.

The concerning symptoms pointed to a rare and potentially fatal condition called acquired methemoglobinemia, in which exposure to certain chemicals or medicines changes the shape of a person's hemoglobin molecules, causing their blood to stop releasing oxygen into the surrounding tissue, Warren said.

As a result, tissues become blue and the blood that is now "selfishly holding onto the oxygen" darkens from a "bright brilliant red color" to a "chocolaty brown," he said.

Methemoglobinemia can also be passed down through families, though that form is much rarer.

In this instance, doctors say the woman's condition was triggered by a reaction to a topical pain medication she used to soothe a toothache. The medicine contained benzocaine, the active ingredient in a number of over-the-counter anesthetic ointments.

Benzocaine is also often used by doctors and nurses to numb patients' noses and throats during procedures. There have been more than 400 reported cases of benzocaine-associated methemoglobinemia since 1971, according to the Food and Drug Administration.

The morning after applying the medicine, the woman, who was not named in the report, told doctors she woke up feeling short of breath, Warren said.

Then, she saw herself in the mirror, became "very concerned" and rushed to the hospital, he said.

"'I am blue,'" the woman informed medical staff upon arrival, according to Warren. Her blood samples also showed the telltale discoloration, he said.

Warren emphasized that the woman's blood was brown, not dark blue as other media outlets have reported.

Throughout his career, Warren has seen only one other patient with the disorder but still vividly recalls the signs.

"It's the kind of thing that sticks with you," he said.

Once doctors learned about the benzocaine, they quickly connected the dots and administered the aptly named antidote, methylene blue, Warren said.

Methylene blue returns the altered hemoglobin to its normal form, restoring the blood's ability to deliver oxygen.

Blood samples from the 25-year-old woman diagnosed with acquired methemoglobinemia. (New England Journal of Medicine)

Blood samples from the 25-year-old woman diagnosed with acquired methemoglobinemia. (New England Journal of Medicine)

Lab results later confirmed the diagnosis, revealing that 44 percent of the hemoglobin in the woman's body had been affected, according to the case report.

Patients with levels of more than 50 percent can be at risk for heart failure, coma or even death, Warren said.

"She was on that precipice, for sure," he said.

In a 2018 announcement about the danger of benzocaine products and methemoglobinemia, the FDA noted that it identified 119 reports of the condition within the past decade, most of which were serious and required treatment.

Of those cases, four people, including one infant, died. The federal agency warned that any oral drugs containing benzocaine should not be used to treat infants and children younger than 2 years old, a demographic that is particularly susceptible to the blood disorder, Warren said.

"These products carry serious risks and provide little to no benefits for treating oral pain, including sore gums in infants due to teething," the FDA wrote.

It is unclear how much benzocaine the woman used, but Warren said even small amounts can be dangerous depending on the person.

"This is a medicine that is commonly used with no problem all the time," he said. "There's certain people out there who have this idiosyncratic reaction, and you won't know it until it happens."

The woman received two doses of methylene blue administered through an IV and responded well to the treatment, Warren said. She spent one night in the hospital before her symptoms cleared up and she was discharged with a referral to the dentist.

Warren said he and another doctor decided to publish the details of the woman's experience on Thursday given its rarity, adding that it was a "very interesting physiological case."

"I might work another 20 years and may never see anything like this again," he said.

2019 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.