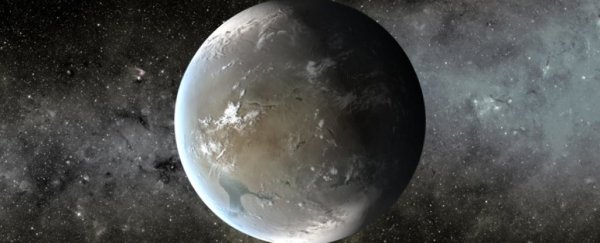

Scientists have identified a new exoplanet candidate that could eventually support human life: Kepler-62f, located some 1,200 light-years away from Earth.

Kepler-62f's potential habitability is based on it being a suitable distance from its sun, and astronomers think this might give it the necessary mix of solid, rocky terrain and oceans to support life. The planet is about 40 percent larger than our own, so at least there's room to spread out, if we ever get there.

The exoplanet got its name because it was discovered by NASA's Kepler mission in 2013, but a new analysis from a team at the University of California, Los Angeles takes a closer look at the composition of the planet, its orbit, and the type of atmosphere it might have.

Multiple composition and orbit hypotheses were tested through a computer model during the course of the research, and the team has estimated that the planet is further away from its star than we are from the Sun, so more carbon dioxide would be required in the atmosphere to keep water in its liquid form on the surface.

By crunching the numbers in terms of potential atmospheric pressure and potential carbon dioxide levels (up to 2,500 times of those on Earth), the astronomers were able to come up with a number of habitable scenarios that made statistical sense.

With Kepler-62f being so far away, actually monitoring the planet's surface is out of the question for now, so these computer models of its atmosphere are the most accurate estimates we've got.

"We found there are multiple atmospheric compositions that allow it to be warm enough to have surface liquid water," said lead researcher Aomawa Shields. "This makes it a strong candidate for a habitable planet."

Very high concentrations of carbon dioxide would be required to keep Kepler-62f warm enough to be consistently habitable for the whole year, the researchers say. So high, in fact, that the planet would require an atmosphere that's three to five times thicker than Earth's and composed entirely of carbon dioxide.

That might sound like a lot, but you'd need that much carbon to trap heat in the planet's atmosphere, given how far away Kepler-62f is from its star. The team also discovered "certain orbital configurations" that would allow temperatures to get above freezing for particular parts of the year.

Shields says the methods used in this research, where two different types of computer model were combined, could also help astronomers study other exoplanets outside our Solar System, filling the gaps in the data that we can't yet get from telescopes.

At the moment, only a few dozen exoplanets (out of around 2,300 discovered so far) are in what's known as the 'habitable zone', where it's possible that life could be supported – essentially, environments where running liquid water might be found.

"[These models] will allow us to generate a prioritised list of targets to follow up on more closely with the next generation of telescopes that can look for the atmospheric fingerprints of life on another world," said Shields.

The findings have been published in Astrobiology.