A name on the tip of your tongue. That fuzzy feeling when the fact you learned just yesterday has floated out of reach. Recalling memories and tidbits of information can be exasperating at the best of times, and even harder when you're sleep deprived.

But what if there was a way to reverse that sleep-deprived amnesia and retrieve those flimsy memories?

A new study in mice suggests that 'forgotten' memories can be recovered days later, by activating select brain cells or with a drug typically used in humans to treat chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a group of diseases affecting the lungs and airways, including emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and asthma.

That might seem bonkers, but not so much when you think about how memories are somehow chemically encoded in brain cells.

And while the possibility of replicating this in humans is somewhat fanciful, the study does reveal a thing or two about new memories we thought we'd lost to sleepless nights.

Past research has shown how even brief periods of sleep deprivation affect memory processes, altering protein levels and brain cell structure. But researchers were still unsure whether sleep loss impairs how information is stored, making it difficult to access later, or if newly formed memories are lost altogether when we haven't slept.

This was the first question University of Groningen neuroscientist Robbert Havekes and colleagues set out to answer, using mice who were deprived of sleep for 6 hours after scoping out a cage with several objects.

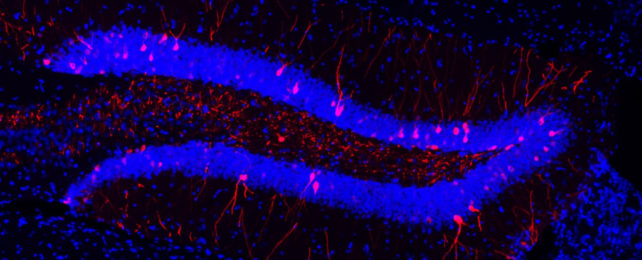

Days later, the animals failed to detect that one of the objects had been moved to a new position – unless certain neurons in the hippocampus, a slender brain region that stores spatial information and consolidates memories, were activated using light.

This shows that the mice could remember where the original objects were located, if the hippocampal neurons encoding that information were given a nudge. "The information was, in fact, stored in the brain, but just difficult to retrieve," explains Havekes.

The findings suggest that memories thought to be 'lost' may still exist in some inaccessible state and can be artificially retrieved, at least in mice.

But the technique used to do this, optogenetics, is an experimental approach that requires a genetic tweak (to make cells light-sensitive) and as such, is still a long way from being used in humans.

To experiment more in mice with a less invasive approach, the researchers turned to a COPD drug called roflumilast. Among the pharmaceutical's varied effects is a boost to levels of a specific cell signaling molecule that becomes diminished when memory is impaired due to sleep loss.

"When we gave mice that were trained while being sleep deprived roflumilast just before the second test, they remembered, exactly as happened with the direct stimulation of the neurons," says Havekes.

The memory-restoring effects with roflumilast were apparent 5 days after the initial training, and even longer when both the drug and light activation were used.

While the work of Havekes and team is focused on unraveling molecular mechanisms of memory and how to restore it, their new research raises some age-old questions about how memories – the rich, sensory imprints of past experiences which color our lives – are encoded in squishy brain tissue.

For centuries, scientists have pondered and then searched for networks of brain cells in which they thought distinct memories were stored. Called engrams, the connectivity and strength of these networks is thought to be key to storing memories.

At times, the existence of engrams as the basic unit of memory was doubted. But memory engram research has had a recent resurgence now that scientists have the right tool to manipulate individual populations of brain cells: optogenetics.

Using optogenetics, researchers have elicited fear-related 'freeze' responses in mice by reactivating a subset of hippocampal neurons that were active during an earlier, fearful experience.

They've also seeded a false memory that caused mice to fear a foot shock in the absence of environmental cues and even stimulated memory retrieval in amnesic mice that serve as a model of early Alzheimer's disease.

Though it remains for now in the realms of animal studies, the long-term goal of this kind of research is to understand how information is acquired, stored, and recalled in humans – and possibly, one day, to find a way to help people whose memory recall has been impaired.

"For now, this is all speculation of course, but time will tell," Havekes says.

The study was published in Current Biology.