A galaxy billions of light-years away is the most distant of its kind we've found to date, embodying yet another challenge to our models of black hole and galaxy formation, and offering a rare glimpse into the early Universe.

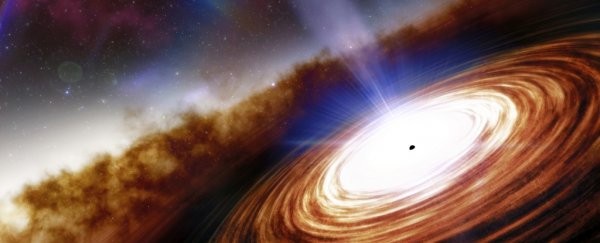

It's named J0313-1806, a quasar over 13 billion light-years from Earth, fully formed with a bafflingly huge supermassive black hole at its centre, and churning out newborn stars at a furious rate - just 670 million years after the Big Bang.

A team of researchers led by the University of Arizona even found evidence of a hot quasar wind, blowing from the supermassive black hole at the centre of J0313-1806 at 20 percent of the speed of light.

"This is the earliest evidence of how a supermassive black hole is affecting its host galaxy around it," said astronomer Feige Wang of UArizona's Steward Observatory. "From observations of less distant galaxies, we know that this has to happen, but we have never seen it happening so early in the universe."

Quasars - a shortening of "quasi-stellar radio sources" - are the incredibly bright result of an active galactic nucleus, with a supermassive black hole accreting material at such a rate that the heat generated blazes across the Universe. J0313-1806's core is accreting material at a rate of 25 solar masses a year; but it's so far away that only the combined might of some of our most powerful telescopes were able to detect it as an infrared dot at the dawn of time.

Then, the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile was used to study it in closer detail. Together, these observations reveal the most distant quasar yet, beating the previous record holder, J1342+0928, by 20 million years.

J1342+0928, identified at 690 million years after the Big Bang, was challenging enough, with a supermassive black hole clocking in at a tremendous 800 million solar masses. But J0313-1806 has it beat hand over fist - its supermassive black hole is twice as massive, at 1.6 billion solar masses.

That's extraordinarily massive so soon after the Big Bang - and too massive for some of our current models. One of the models proposes that supermassive black holes start small and grow by accreting matter. Another proposes that they form via the direct collapse of dense clusters of stars.

These models can work for other quasars found in the distant Universe, such as J1342+0928, but not for J0313-1806. Even if the J0313-1806 supermassive black hole formed around 100 million years after the Big Bang, and grew as fast as modelling allows, it would still need to have started at 10,000 solar masses right from the outset, the team calculated.

There is, however, a third option.

"This tells you that no matter what you do, the seed of this black hole must have formed by a different mechanism," said astronomer Xiaohui Fan of the UArizona Department of Astronomy. "In this case, one that involves vast quantities of primordial, cold hydrogen gas directly collapsing into a seed black hole."

There are other reasons J0313-1806 is a fascinating object. There's its star formation rate, around 200 solar masses a year, classifying it as what we call a starburst galaxy. This is an intense stage in a galaxy's life; at such high rates of star formation, it's only a matter of time before all the star-forming material runs out.

And that quasar wind - extreme hot plasma outflows from the accretion disc of material swirling around the supermassive black hole - isn't helping matters. These winds are stripping the cold star-forming gas from the galaxy, which is thought to eventually extinguish, or quench, star formation.

"We think those supermassive black holes were the reason why many of the big galaxies stopped forming stars at some point," Fan said.

"We observe this 'quenching' at lower redshifts, but until now, we didn't know how early this process began in the history of the Universe. This quasar is the earliest evidence that quenching may have been happening at very early times."

Eventually, there will be nothing left nearby for the supermassive black hole to devour, either, and its brilliant blaze will dim, at least from our point of view. Since the light reaching us from J0313-1806 is 13.03 billion years old, the galaxy probably looks very different now from what we are seeing.

Nevertheless, the quasar, and others like it, constitute a growing catalogue that is helping astronomers piece together the mysteries of how our Universe flared to life. And, as our instruments continue to grow more sensitive, so too will our understanding of the beginning of everything continue to grow.

"Future observations," Wang said, "could make it possible to resolve the quasar in more detail, show the structure of its outflow and how far the wind extends into its galaxy, and that would give us a much better idea of its evolutionary stage."

The research has been presented at the 237th meeting of the American Astronomical Society. It has also been accepted by The Astrophysical Journal Letters, and is available on arXiv.