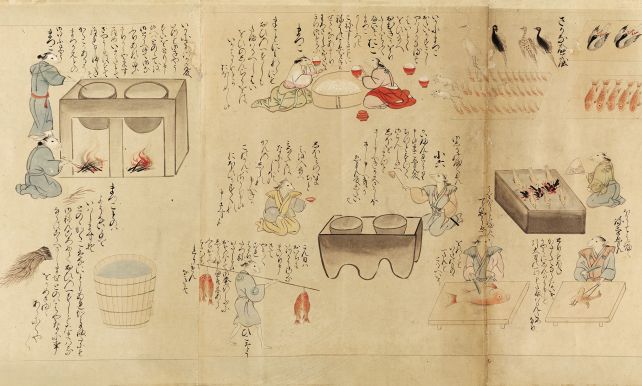

At first glance, it looks like a piece of historical whimsy: a sequential, pictorial account of rats scurrying about in preparation for a wedding feast.

Inked sometime between 1550 and 1650 CE, during Muromachi, Azuchi–Momoyama, or Edo Japan, the anonymous picture scroll titled Nezumi no sōshi emaki – The Illustrated Rat's Tale – is more than an interesting bit of art history.

While early Japanese picture scrolls are considered by some to be the precursor to the manga art form that blossomed and boomed in the 20th century, this particular illustrated fantasy contains valuable information about how food was prepared in medieval Japan.

"There were quite a few stories written in medieval and early modern Japan about rats, and many of these became picture scrolls combining illustrations with text," says University of Kansas historian Eric Rath.

"But what sets this example apart are the detailed scenes of cooking. There is only one other picture scroll that depicts cooking scenes for this period, so as a food historian, I wanted to see what I could learn from this rat story."

In Japanese traditions, rats occupy a place of honor. Far from the symbol of filth and pestilence they represent in western tradition, the rodents were admired for their cleverness and industriousness, and were seen as a symbol of wealth and good fortune. According to folklore, they also could take human form – and sometimes had some pretty wild adventures.

In The Illustrated Rat's Tale, a rat overlord wishes to take a human bride. However, she doesn't know he's a rat, so he and his retinue must perform a sort of masquerade, parading as a human lord and his household as they throw a wedding feast fit for a shogun.

Now kept in the New York Public Library's Spencer Collection, the scroll offers a fascinating look at Japanese political and social climates of the time. But the scene in which the feast is prepared also goes into exquisite cultural detail, Rath found.

"The way the artists depicted rats preparing for a banquet offers insights into the division of labor and workflow of kitchens in elite households in the 16th century, an age with very few other visual sources," he says.

"We learn that specially trained male (rat) chefs handled prestigious tasks like carving meats and female workers performed manual labor such as milling the rice outside."

The rats all have roles and names, and wear clothing that indicates social status. Those of lower status wear simple robes and sashes, while higher status rats wear more elaborate clothing such as kosode and a ceremonial dress for elite male rats, called kamishimo.

They imbibe sake, and have different manners of speaking, bantering back and forth about the difficulties of their jobs. For instance, a rat carving a swan complains about the toughness of the bones therein. Actual historical figures make appearances, such as celebrated tea master Sen no Rikyū, who is also depicted as a rat in the scroll.

Some of the rats have names that indicate greed and consumption: Tōbei the Bean-lover, Bad Tarō the Glutton, and Kuranojō the Rice-Chewer. What's interesting about the story, however, is that it repositions the animals as preparers of food, Rath says, rather than just consumers of it.

Recasting a high-status human household as a pack of rats would have given a glimpse of the lives of the wealthy that few otherwise might have been privy to.

"For a contemporary audience, the society of the human elite was probably as rarified and as inaccessible – and therefore as interesting – as a storybook land in which rats cooked," Rath writes.

"In other words, by showing how rats prepared food, the creators of The Rat's Tale offered a perspective and subtle commentary on elite human society without having to fear the retribution of human overlords."

In the end, alas for the rats, the ruse is discovered: several rats fail to maintain their human facade, and the bride discovers their deception.

The paper has been published in Gastronomica: The Journal of Food and Culture.