Microscopic organisms found in dirt collected from a hike through Nova Scotia mean we're going to have to add another branch to the tree of life.

The strange organisms simply don't fit into the plant kingdom, the animal kingdom, or any other kingdom we've classified up until now.

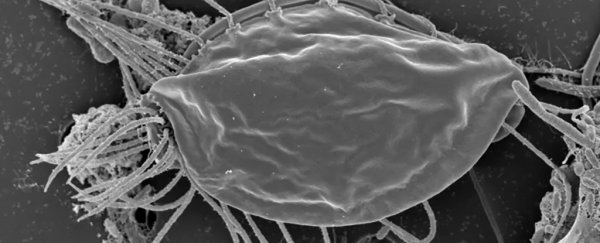

The tiny critters in question represent two species of the group of microbes called hemimastigotes, and based on a detailed genetic analysis, one of them has never been spotted before.

According to the team of researchers from Dalhousie University in Canada, the two species are eukaryotes (with complex cells, like humans), and protists (outside the animal, plant, and fungi kingdoms). But they don't fit the patterns of the existing 10 kingdoms that make up the Eukaryota domain.

(Yana Eglit)

(Yana Eglit)

"This discovery literally redraws our branch of the tree of life at one of its deepest points," says one of the researchers, Alastair Simpson. "It opens a new door to understanding the evolution of complex cells – and their ancient origins – back well before animals and plants emerged on Earth."

The first hemimastigote species to be identified was Spironema, which has only ever been spotted a handful of times. A second completely new species was then discovered – the scientists named it Hemimastix kukwesjijk, after the Kukwes ogre in the folklore of the local Mi'kmaq people.

This microbe looks and acts like a miniature ogre, the researchers say, in the way it traps and eats food.

"It's an unusual looking group of organisms," says one of the team, Yana Eglit. "The way they behave under the microscope, you won't immediately spot them."

The first hemimastigote was identified in the 19th century, but before now scientists haven't been able to do a detailed genetic analysis on these microbes. They have always been something of a mystery when it comes to classification.

With the help of a relatively new gene sequencing technique called single-cell transcriptonomics – which can glean the same amount of data from a handful of cells as other techniques can from millions – the team was able to confirm that these organisms don't fall into the tree of life branches already identified by scientists.

In fact they're more different from other organisms as animals and fungi are from each other. To find a common ancestor between hemimastigotes and any other living creature you would have to go back about a billion years, the researchers suggest.

"They represent a major branch… that we didn't know we were missing," Simpson told Emily Chung at CBC News. "There's nothing we know that's closely related to them."

What makes the discovery all the more remarkable is that Yana Eglit only collected the crucial samples on a whim during a spring hike with other students along the Bluff Wilderness Trail outside Halifax.

When studying the microbes under a microscope, Eglit noticed that the flagella (or tiny hairs) on the organisms appeared to be moving in a random rather than a coordinated fashion – that's unusual, and one of the signs of a rare hemimastigote.

The researchers were even able to feed and breed captive Hemimastix kukwesjijk microbes, which means we won't have to rely on fortunate woodland hikes to have more opportunities to study them. Further research might give us more insight into the very earliest history of the evolution of life.

And despite playing such a major role in the discovery, Yana Eglit is keen to emphasise the work behind this fascinating development in the tree of life was a team effort.

"We would have not been able to do this work alone as one lab," says Eglit. "Everyone involved in this was essential."

The research has been published in Nature.