For hundreds of years, the world's best cryptographers have dedicated their lives to solving the mystery of the Voynich Manuscript - a 15th century book written in a mysterious coded language that no one has ever managed to crack.

With an unknown author - and rumours that a young Leonardo da Vinci or even aliens could be behind it - the Voynich Manuscript has become the stuff of legend. But now new research suggests that the whole thing could just be one elaborate hoax.

Often referred to as the world's most mysterious book, the Voynich Manuscript is filled with what appears to be an unfamiliar language or a coded text, and is illustrated with grotesque human figures and the tendrils of other-worldly plants blooming from the borders.

As the text could not be attributed to an author, it's been named after Lithuanian antiquarian Wilfrid Voynich, who reportedly purchased it in 1912 from a collection of rare books in Italy, and was responsible for bringing it out of obscurity and into the public consciousness.

Since then, the book has never been replicated, and has been locked away in the vault of Yale University's Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library. Because of its age and incredible rarity, very few researchers have actually seen it in person.

"Touching the Voynich is an experience," Juan Jose Garcia, director of the Spanish publishing house Siloe, told Agence France-Presse. "It's a book that has such an aura of mystery that when you see it for the first time … it fills you with an emotion that is very hard to describe."

As we reported last month, Garcia has finally been given permission to produce the first ever replicas of the Voynich Manuscript.

The hope is that when 898 exact copies of the manuscript are made available to the public in libraries and academic institutions around the world, someone - anyone - will finally crack the code.

But are we wasting our time trying?

Gordon Rugg of Keele University in the UK has spent more than a decade studying the Voynich Manuscript, and argues in a new paper that the elaborate 'language' in the text would have been easy to fake, if the author was familiar with a few simple coding techniques.

"We have known for years that the syllables are not random. What I'm saying is there are ways of producing gibberish which are not random in a statistical sense," he told Rebecca Boyle from New Scientist.

"It's a bit like rolling loaded dice. If you roll dice that are subtly loaded, they would come up with a six more often than you would expect, but not every time."

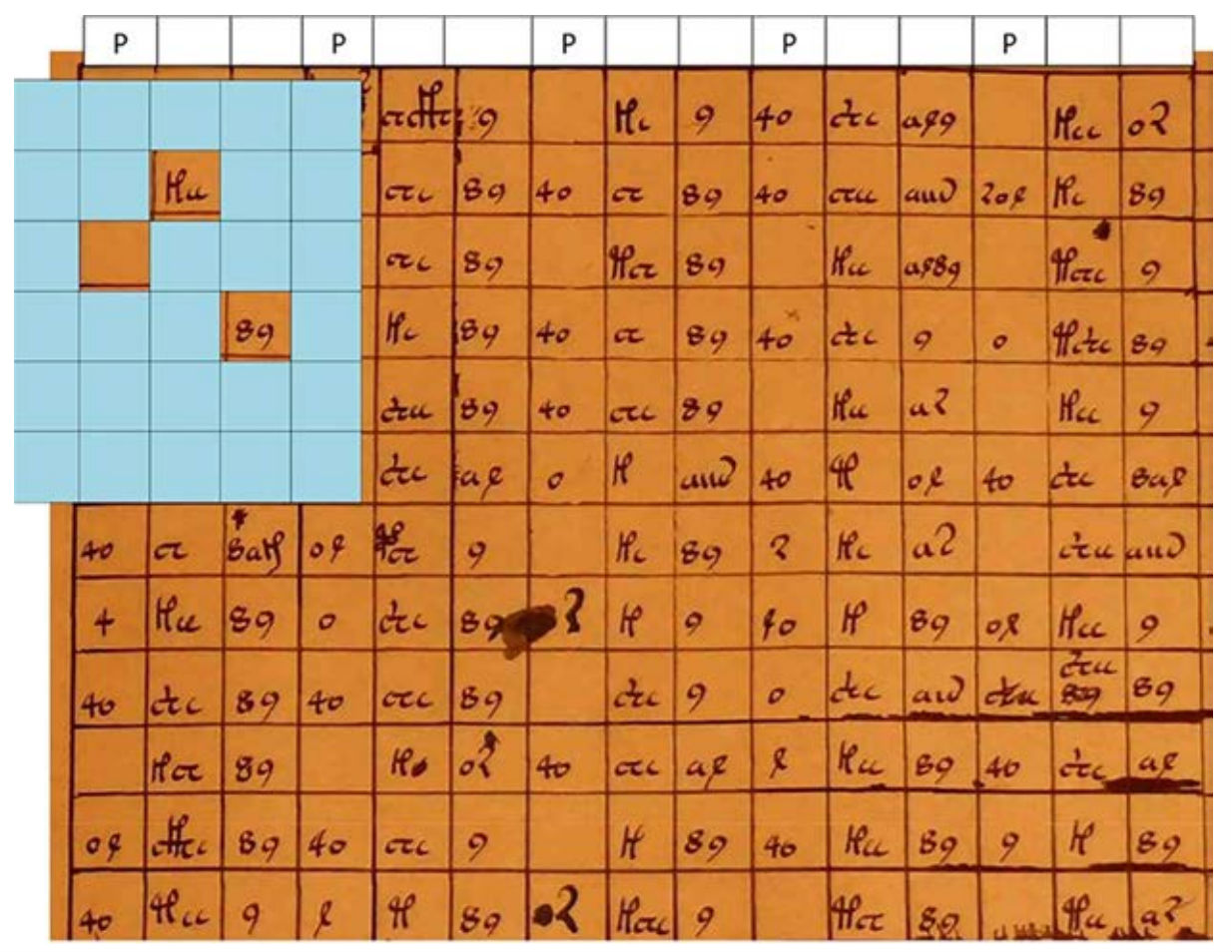

The method Rugg proposes for coming up with a language based on gibberish that at least looks genuine is coming up with a whole range of gibberish symbols, and arranging them on a table like so:

Rugg et. al.

Rugg et. al.

On his table, he included symbols that appear to be the roots, prefixes, and suffixes of Voynichese words.

You'll then have different 'grilles' - a piece of cardboard with holes cut in it - and the holes in these grilles will reveal a set of three gibberish symbols to produce a word.

If you move across the table, using grilles with different hole positions as you go, you'll soon come up with many different combinations of syllables to produce whole Voynichese words.

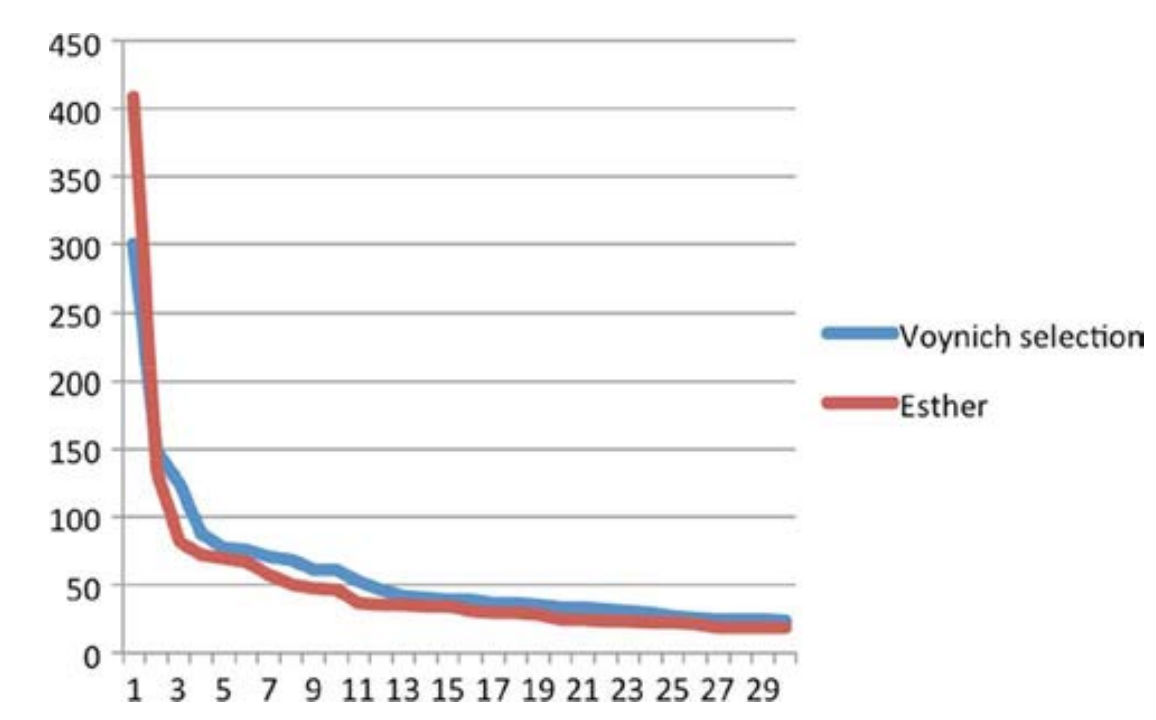

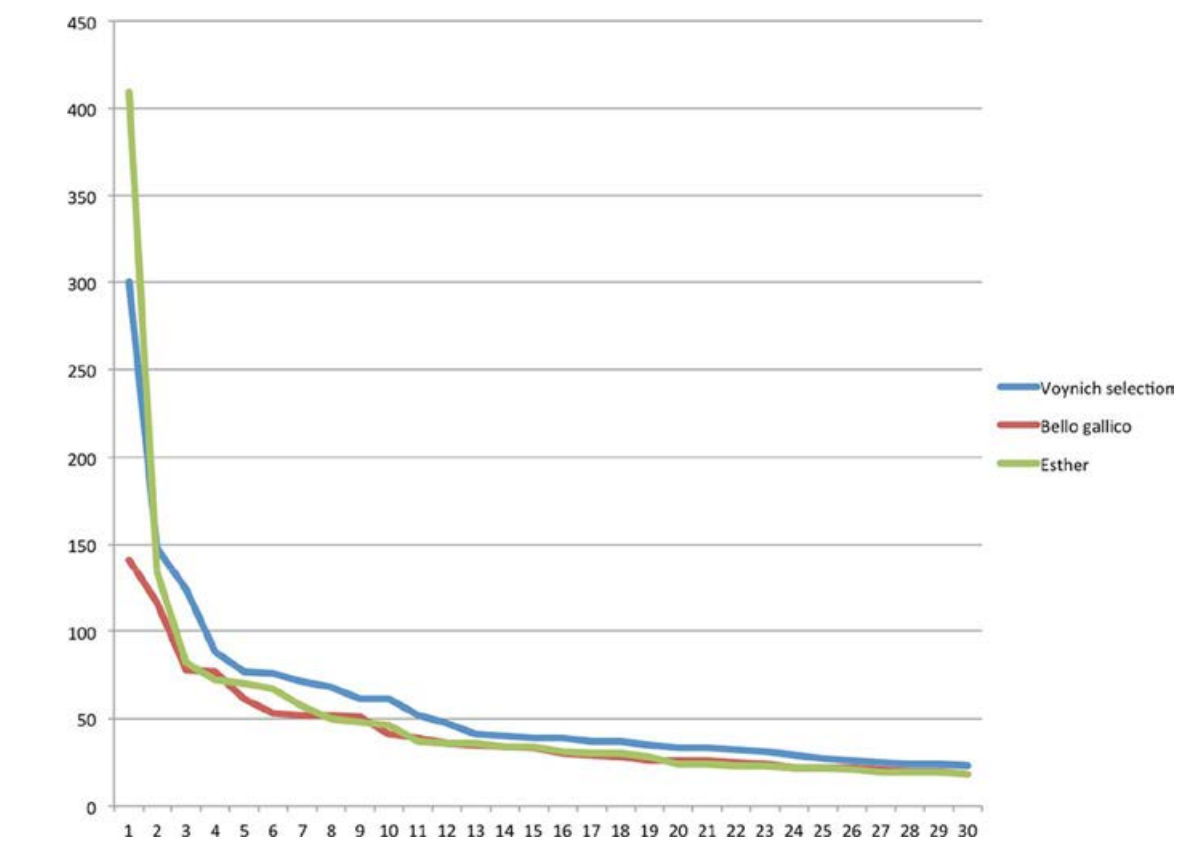

Once Rugg had his results, he wanted to see if the text followed Zipf's law, which describes the relative frequencies of words within a real written language.

As you can see in the graphs below, which compare his Voynichese selection to the Vulgate Latin translation of the Book of Esther and Caesar's De Bello Gallico, he appears to have gotten his answer:

Rugg et. al.

Rugg et. al.

Rugg et. al.

Rugg et. al.

"If the words within a text are ranked from most common to least common, and their frequencies are then plotted on a histogram, then natural language texts typically show a nonlinear curve with a steep initial descent followed by leveling off to a long tail of words that only occur a few times within the text," he writes in his paper.

"The text in the Voynich Manuscript shows this pattern and has a very similar curve to some real natural language texts."

So is the legend dead after all this time? Well, not everyone is convinced by Rugg's evidence.

Marcelo Montemurro from the University of Manchester in the UK, who wasn't involved in the study, argues that the manuscript does contain meaningful text, based on his own statistical analysis comparing Voynichese words to several classic texts written in various languages.

He told New Scientist that the Voynich Manuscript text has far too many layers of complexity for a simple hoaxer to produce, and says he's found statistical similarities between the botanical and pharmaceutical sections of the manuscript, and has been able to link the art to corresponding, indecipherable words.

"That means whoever made the hoax was aware of these subtle layers of structure that are very difficult to find just by looking at the text," he says.

"We cannot say for certain whether it is a hoax, or hides a message. But we can say, whoever wants to propose that it is a hoax needs to explain how all of this can arise spontaneously without the author planning all these things."

At this stage, the researchers will have to agree to disagree, because Rugg maintains that he's demonstrated how simple it would be for the Voynich's author to make gibberish look genuine, and the burden of proof now lies on the 'true believers' to demonstrate the veracity of this language.

But he admits, "I don't think there will ever be a resolution that everybody will be happy with."

As the replica publisher Garcia told the AFP last month, the mysterious author might have been a genius, but "could also have been a sadist, as he has us all wrapped up in this mystery".

Rugg's research has been published in Cryptologia.