Nanomaterials have been crucial in many recent scientific advancements, but the miniature size of these objects makes it difficult to clear them up when they end up in places they shouldn't, like our oceans and waterways. Fortunately, researchers in the US have come up with a method that could see these nanomaterials filtered from contaminated water.

"Look at plastic," explains one of the team, Yoke Khin Yap from Michigan Technological University. "These materials changed the world over the past decades - but can we clean up all the plastic in the ocean? We struggle to clean up metre-scale plastics, so what happens when we need to clean on the nano-scale?"

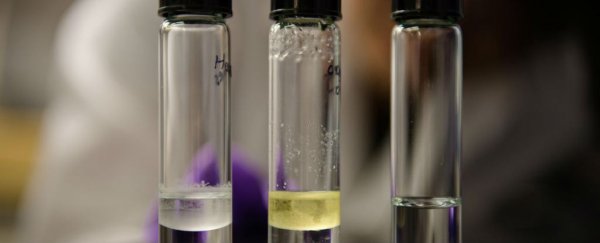

The method sounds like something out of a recipe book: add a little water, and a little oil, then shake. As oil and water don't mix well, they separate out during the shaking process, with the oil trapping any nanomaterials in the solution as it goes.

Experiments were run using different types of nanomaterials, including carbon nanotubes, graphene, boron nitride nanotubes, boron nitride nanosheets, and zinc oxide nanowires, which you can find in items such as carbon fibre golf clubs and sunscreen. If we're going to be relying on these super-materials in the future, we need to be sure they won't have an adverse effect on our environment, and this study is a part of that analysis.

"Ideally, for a new technology to be successfully implemented, it needs to be shown that the technology does not cause adverse effects to the environment," explains the report, published in Applied Materials & Interfaces. "Therefore, unless the potential risks of introducing nanomaterials into the environment are properly addressed, it will hinder the industrialisation of products incorporating nanotechnology."

According to the US Environmental Protection Agency, more than 1,300 commercial products use some kind of nanomaterial - a figure that's likely to rise sharply in the future - and at the moment we don't know as much as we really should about their full impact on health and the environment.

Alternative methods such as filter paper and meshes often aren't effective enough at cleaning up nanomaterials, says team leader Dongyan Zhang, which is why he and his colleagues settled on the oil and water solution. "These materials are very, very tiny, and that means if you try to remove them and clean them out of contaminated water, that it's quite difficult," he said.

His team's findings should help spur nanotechnology development, as cleaning up after these materials is relatively straightforward.