Researchers have developed a patch that can be stuck onto the heart to improve the conduction of electrical impulses – something that could lead to less complications for victims of heart attacks.

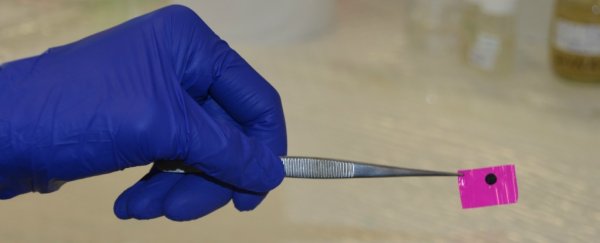

The polymer patch, which is long-lasting and flexible, is designed to limit cardiac arrhythmia - dangerous heart rhythm disturbances that can occur after a heart attack.

Researchers from Imperial College London, in the UK, worked with The University of New South Wales (UNSW) Faculty of Science in Australia to develop the patch.

"Heart attacks create a scar which slows and disrupts the conduction of electrical impulses across the heart," says one of the team Sian Harding from Imperial College.

"This leads to potentially fatal disturbances of the heart rhythm. Our electrically conducting polymer patch is designed to address this serious problem."

In case you've forgotten the intricacies of high school anatomy, our hearts beat because of a cluster of cells at the top of the organ called the SA node. It's basically our natural pacemaker.

When the SA node sends out an electrical impulse, each of the heart chambers contracts in a specific order, allowing blood to be pumped through the heart and around the body.

But when someone has a heart attack, the scar tissue that forms limits that electrical impulse signal and how far it can travel, which can cause an irregular heartbeat, and other heart problems.

Using rats, the team found that when the patch was attached, it improved conduction of electrical impulses across heart scar tissue, which should lead to less complications after a heart attack.

"We envisage heart attack patients eventually having patches attached as a bridge between the healthy and the scar tissue, to help prevent cardiac arrhythmia," says co-lead researcher from UNSW Damia Mawad.

"However, our patch is at the very early stages of this research. This technology can now be used for basic research to gain insights into the interface between the material and tissue."

The patch is made from chitosan, which is found in crab shells, and a conducting polymer called polyaniline. Phytic acid is also added to help the polyaniline conduct electric impulses.

"Our suture-less patch represents a big advance. We have shown it is stable and retains it conductivity in physiological conditions for more than two weeks, compared with the usual one day of other designs," says Mawad.

"No stitches are required to attach it, so it is minimally invasive and less damaging to the heart, and it moves more closely with the heart's motion."

The patch is then stuck to the heart by shining a green laser on it – a technique developed by another researcher at UNSW.

"The patch can help us better understand how conductive materials interact with heart tissue and influence the electrical conduction in the heart, as well as better understand the physiological changes associated with heart attacks," says Molly Stevens from Imperial College London.

We're looking forward to seeing where this life-saving technology can go from here.

The research has been published in Science Advances.

UNSW Science is a sponsor of ScienceAlert. Find out more about their world-leading research.