After more than a decade of searching, scientists working in South America have stumbled across the oldest fossilized grape seed ever found in the western neotropics.

The tiny, 60 million-year-old fossil's location suggests that grape vines started to spread around the world from an origin in what is now South America shortly after the extinction of most dinosaurs roughly 66 million years ago.

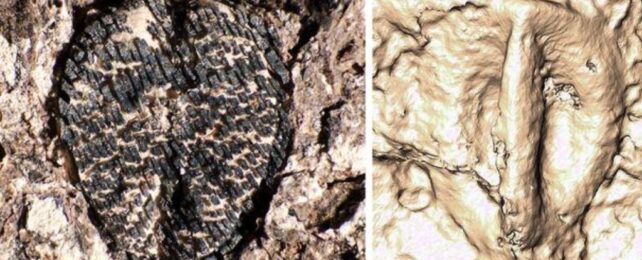

The fossil of the prehistoric seed was unearthed in Colombia in 2022, much to the delight of paleobotanist Fabiany Herrera from Chicago's Field Museum.

Herrera's colleague, Mónica Carvalho, was the first to find the primeval pip on a rock in the Andes.

"She looked at me and said, 'Fabiany, a grape!' And then I looked at it, I was like, 'Oh my God.' It was so exciting," recalls Herrera.

"I've been looking for the oldest grape in the western hemisphere since I was an undergrad student."

A single prehistoric grape seed may not seem that important in the grand scheme of life on Earth, but soft-tissued fruit is rarely preserved in the fossil record, and the age of the seed has Herrera, Carvalho and colleagues rethinking the deep history of grape vines on the continent.

Today, from Mexico to Patagonia, there exist roughly 100 species of grape vine, and yet the fossil record of this mainly tropical family is patchy and historically biased toward North America and Eurasia.

In 2013, scientists at the Florida Museum discovered fossilized grape seeds in India, which were almost 10 million years older than those found in Europe or North America. Even since, Herrera has been on the hunt for a similar discovery in the western neotropics of the Americas and the Caribbean.

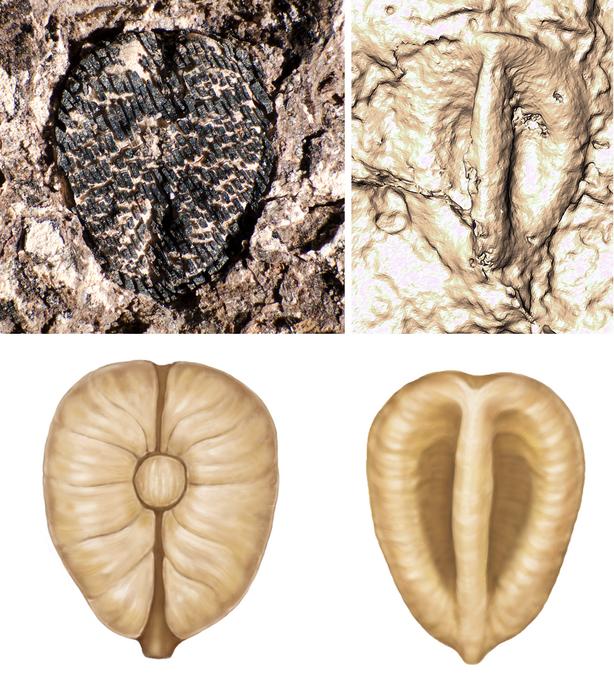

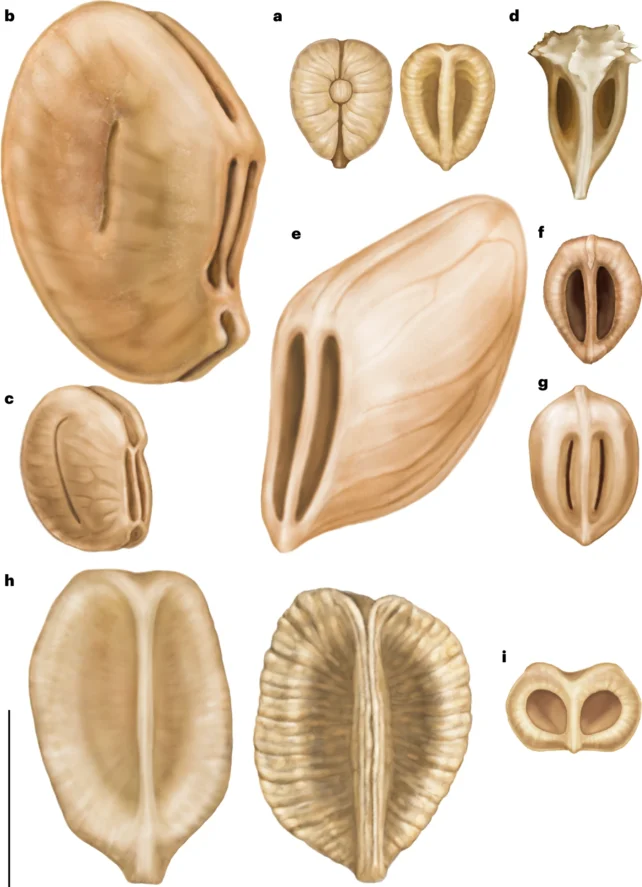

Along with the 60-million-year-old fossil seed left by a species researchers have named Lithouva susmanii, Herrera and his team have also described eight other grape seed fossils in Central and South America.

Several of the fossils were discovered in what is now Panama and Peru, but they are distantly related to Old World genuses half a world away. These genuses were once thought to be restricted to Asia, but the new research suggests the seeds spread further and faster around the world than scientists bargained on.

By contrast, a 19-million-year old seed from the genus Ampelocissus was found in Panama and is "remarkably similar" to living species in the Caribbean and Mesoamerica, which suggests the genus originated nearby before spreading to other continents.

The reasons for the emergence and spread of all these grape seeds seem to be tied to the loss of dinosaurs. They only show up in the fossil record after this extinction event.

"We always think about the animals, the dinosaurs, because they were the biggest things to be affected, but the extinction event had a huge impact on plants too," says Herrera.

"The forest reset itself, in a way that changed the composition of the plants."

Grape vines thrive in crowded forests, where they twist and turn through the understory and canopy, latching onto other plants for support. Without dinosaurs pruning the forests back, grape vine plants may have had room to grow.

"Large animals, such as dinosaurs, are known to alter their surrounding ecosystems," explains Carvalho.

"We think that if there were large dinosaurs roaming through the forest, they were likely knocking down trees, effectively maintaining forests more open than they are today."

When our planet loses life, it doesn't take long for something else to fill in the gaps. If Herrera and his colleagues are right, we can thank the dinosaur's big exit for allowing our species to eventually domesticate tropical grape vines roughly 8,000 years ago.

Cheers to that!

The study was published in Nature Plants.