Among the roughly 370,000 known species of flora sprouting on Earth's surface, a taste for blood is rare. But only one plant is known to be carnivorous on a part-time basis.

Triphyophyllum peltatum is a rare plant from the tropical forests of Sierra Leone in West Africa known to trap insects from time to time. Until recently, researchers have had a hard time cultivating the plant successfully enough to determine just what triggers its sudden hunger for bug meat.

Now researchers from Leibniz University Hannover and the University of Wurzburg in Germany have uncovered a few more intriguing details on the life of a most unique carnivorous plant.

This species of liana or woody vine is of particular interest to science for more than its diet, containing pharmaceutically active chemicals that may be useful against malaria and some cancers.

In its juvenile stage, T. peltatum is surprisingly ordinary-looking. It soaks up sunshine and generates energy through photosynthesis, displaying no signs of its penchant to snare prey. Mature plants will start to unfurl leaves with two hooks at the tip that assist with their climb to the sun-filled canopy.

As it develops, however, the growing vine can sometimes sprout glandular leaves that ooze fat blobs of sticky, blood-colored liquid capable of trapping unsuspecting beetles for digestion.

Then, once satisfied, the plant might drop its carnivorous habit altogether.

Unlike other carnivorous plants, such as the Venus flytrap, sundews, bladderworts, and butterworts, the insect-eating behavior of T. peltatum is not hardwired into its development. Some T. peltatum plants never become meat-eaters.

Scientists have hypothesized T. peltatum, like similar species, turns carnivorous to survive in environments deprived of nutrients such as nitrogen. But, until now, scientists had not pinpointed exactly what triggered this metamorphosis, in large part because this is such a difficult plant to cultivate.

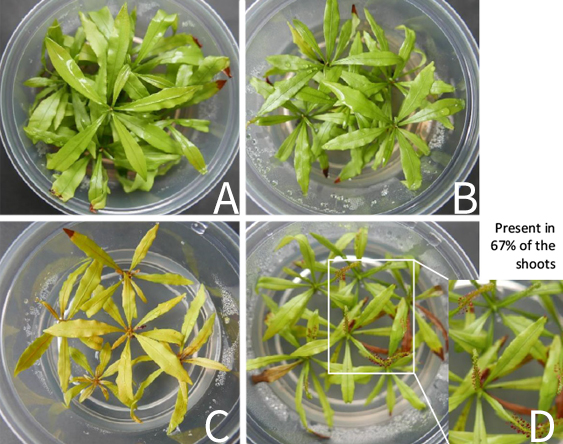

To solve this puzzle, researchers first had to grow T. peltatum from scratch. Using advances in laboratory techniques learned from previous studies on the plant, the team of researchers behind this newest study successfully propagated and raised specimens from the botanical gardens of Würzburg in a lab in Hannover.

Sixty shoots were grown in small plastic vessels that contained soil that was deficient in either nitrogen, potassium, or phosphorus, or a control medium. These plants were checked every week for six months to see whether they became carnivorous or not.

The only plants that grew the distinct, red-dotted, glandular leaves were those deprived of phosphorus. This result was replicated in plants grown in glasshouses with low levels of phosphorus in the soil.

Phosphorus is a critically important mineral for the growth and development of plants; it is used to make core components of DNA and membranes.

Plants invest significant energy towards growing in an extensive root system to soak up phosphorus in the soil. But towards the end of the dry season, plants can start to experience phosphorus starvation.

This is the time of year when T. peltatum mostly grows its insect-catching leaves.

Carnivory is energy intensive as it requires the production of sticky glue and digestive enzymes to break down animal matter.

"When the [phosphorous] concentration drops below a critical threshold, T. peltatum invests in the formation of carnivorous leaves to be able to complement their phosphorous stocks from captured animals," the researchers write.

"After soil phosphorus content recovers to pre-stress levels, 'cheaper' photosynthesis leaves get produced."

This paper was published in New Phytologist.