The near-Earth asteroid responsible for the spectacular annual Geminids meteor shower has been caught doing something really unexpected.

Scientists studying the shifting light of 3200 Phaethon have concluded the rocky body is spinning faster and faster on its axis, shaving off around 4 milliseconds every year. That might not seem like a lot, but asteroid spins don't usually change at all.

Figuring out why Phaethon is behaving this way could give us new insight into a class of asteroids considered "potentially hazardous" – skimming past Earth as they orbit the Sun.

Phaethon currently poses no danger to Earth, but at 5.8 kilometers (3.6 miles) across it's large enough to cause no small amount of pain were it to hypothetically hit. What's more, the asteroid's path brings it close enough that enough of a change in its 524-day orbit could cause us to rethink our concerns.

It's also an oddball. The asteroid's orbit dips in close to the Sun like a comet's, for example. It also has a dusty tail, and happens to be one of just two asteroids that produce meteor showers (mostly those come from comets too).

And yet, unlike a comet, it seems to have no ice. Scientists have referred to it as a "rock comet".

Oh, and it's strikingly blue. Most asteroids are reddish, or gray.

Phaethon's unusual characteristics have made it the target of a future lander mission, DESTINY+ (Demonstration and Experiment of Space Technology for INterplanetary voYage with Phaethon fLyby and dUst Science), spearheaded by the Japanese Space Agency. So scientists have been working on learning more about the strange rock, to better plan how to rendezvous with it.

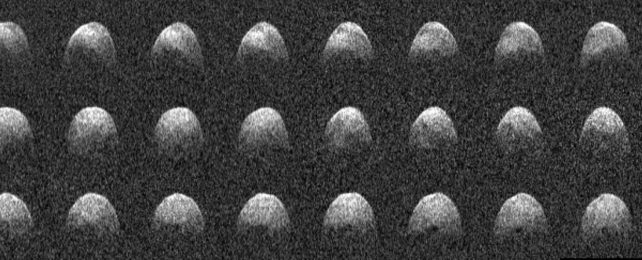

Phaethon's brightness changes as it rotates, which means that we have been able to characterize its rotational period over time, narrowing it down to 3.6 hours. But we need precise data if we're going to land a probe on this thing, so planetary scientist Sean Marshall of Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico was working to refine Phaethon's size, shape, and rotation when he noticed something screwy.

He presented his team's findings last week at the American Astronomical Society's 54th Annual Meeting of the Division for Planetary Sciences.

"The predictions from the shape model did not match the data," Marshall says.

"The times when the model was brightest were clearly out of sync with the times when Phaethon was actually observed to be brightest. I realized this could be explained by Phaethon's rotation period changing slightly at some time before the 2021 observations, perhaps from comet-like activity when it was near perihelion in December 2020."

A closer look at the full dataset, spanning the period from 1989 to 2021, revealed that the change could be explained by a gradual, constant acceleration, losing 4 milliseconds of the rotation period a year. Year-on-year, the change doesn't make a lot of difference, but as the decades rack up, it's become much more prominent.

In fact, a team of researchers noticed a discrepancy in the rotational period back in 2016, when they noticed that their data was out of sync with 1989 data. At the time, the researchers didn't have quite enough information to explain the difference. Now, that discrepancy appears to be resolved.

This makes Phaethon one of just 11 asteroids with accelerating rotations, out of the thousands of asteroids whose rotations have been characterized. It's possible that this is the result of mass loss; outgassing in comets produces a spin-up effect, and a study last year found that Phaethon may outgas sodium.

It's also possible that a small Yarkovsky-O'Keefe-Radzievskii-Paddack (YORP) effect may apply. This is when the heat of a star influences the spin rate of a small body, like an asteroid.

More work will need to be done to figure out what, exactly, is going on with Phaethon; but knowing that the spin rate is changing, and the rate at which it is changing, is an excellent finding in and of itself.

"This is good news for the DESTINY+ team," Marshall says.

"A steady change means that Phaethon's orientation at the time of the spacecraft's flyby can be predicted accurately, so they will know which regions will be illuminated by the Sun."

The team presented their findings at the American Astronomical Society's 54th Annual Meeting of the Division for Planetary Sciences.