The crash of conflicting beliefs jousting inside your head could leave you with more than just an aching brain. It could cause physical pain in your neck and back, according to a new study that had volunteers lift lightweight boxes whilst being told they were doing an unsatisfactory job.

The team of researchers from The Ohio State University and the University of Michigan in the US lumped critical feedback on volunteers after telling them they were executing the lifting task well. The resulting psychological distress added extra pressure on participants' necks and low backs, the researchers found.

While only small, the study could have implications for workplace safety that should recognize how psychosocial stressors, and specifically cognitive dissonance, may harm physical health.

"Basically, the study scratched the surface of showing there's something to this," explains William Marras, a biomechanics researcher at The Ohio State University.

Researchers like Marras have come to appreciate that pain involves a complex interplay between body and mind. But it has taken decades for the 'biopsychosocial' model of pain to really catch on after it was first described in the 1980s.

Pain is a heady mix of physical, social, and psychological stressors, meaning it can manifest out of physical strain coupled with financial stress and mental ill-health. Even the words a doctor uses to describe low back pain can shape someone's expectations of recovery.

"To achieve the goal of treating patients rather than spines, we must approach low-back disability as an illness rather than low-back pain as a purely physical disease," orthopedic surgeon Gordon Waddell wrote back in 1987.

Most research to date, however, has revolved around the coexistence of chronic pain with depression, anxiety, and a tendency to catastrophize (thinking the worst will happen or that things won't change). Marras and colleagues wanted to understand if another psychological factor, cognitive dissonance, also impacts back and spine pain.

Think of cognitive dissonance as the psychological whiplash that arises when you attempt to reconcile multiple, seemingly incompatible beliefs. The difficulty can cause anguish that drives us to seek some kind of mental relief.

Marras and colleagues designed a series of experiments to see whether this psychological discomfort manifests physically, similar to how depression and anxiety can exacerbate pain.

"To get at that mind-body connection, we decided to look at the way people think and, with cognitive dissonance, when people are disturbed by their thoughts," explains Marras.

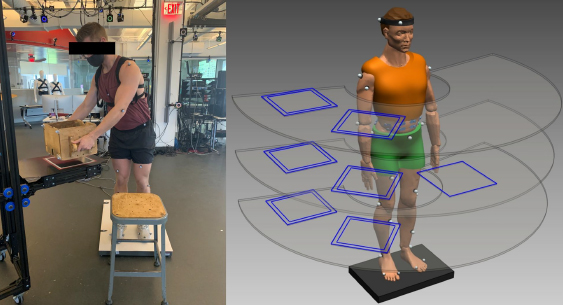

In the lab-based study, 17 volunteers were tasked with moving a lightweight box into precise positions while wearing motion sensors to measure how much load they were putting on their spines and backs.

During practice runs, they were told they were moving in the right way to protect their backs. But then the feedback became increasingly negative, the participants were told they were performing the task in an unsatisfactory way.

When comparing the participants' discomfort scores to the mechanical loads on people's spines, the researchers found that peak spinal loads increased by between 10 and 20 percent when people felt distressed by negative feedback compared to when they were feeling capable at the start of the task.

"This increased spine loading occurred under just one condition with a fairly light load," explains Marras. "You can imagine what this would be like with more complex tasks or higher loads."

In other words, repeated psychosocial stressors may place greater strain on the spine, leading to pain – although that remains to be tested.

Loads on the lower back also increased, but only slightly. Discomfort scores were a combination of physiological measures of stress, including heart rate variation and blood pressure, and surveys of how participants were feeling: either inspired and strong, or ashamed and distressed.

For those who can move uninhibited, remember that low back pain is more than a niggle; it's the leading cause of years lived with disability worldwide.

A recent analysis of three decades of data found that in 2020, nearly 620 million people globally had low back pain – impacting their ability to work, move, travel, or care for themselves or others. That figure is expected to rise to over 800 million people by 2050 – the increasing toll of low back pain makes it clear that conventional treatments, especially addictive opioid medications, aren't working.

Pain research is moving at a clip to figure out how chronic pain starts, understand why it persists, and find effective ways to alleviate it.

Understanding the psychosocial dimensions of pain appears to be helping greatly, with studies finding that adding psychological therapy to physical treatments might be key to overcoming chronic back pain. Indeed, trials of more holistic models of care including group therapy have reduced opioid use without worsening pain.

This latest study adds another dimension to that growing body of research. Only by understanding what adds to people's pain can we hope to relieve it.

The study was published in Ergonomics.